Eye Shadow

As its name suggests, this type of make-up can ‘shadow’ the eyes, making the whites – the sclera – look brighter and the eyes larger and more prominent. A dark-coloured powder (black or brown) can be used which is what many early eye shadows were made with. Helena Rubinstein’s Kohol Jet Grains (1907) used a black powder, while Elizabeth Arden’s Venetian Shading Powder (1914) came in a soft brown.

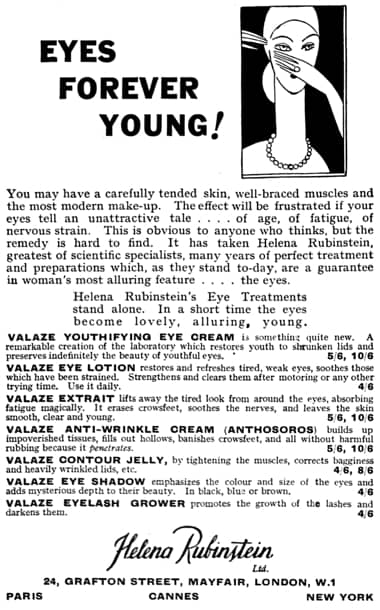

Eye shadow can also be used to accentuate the colour and brilliance of the eyes by ‘shading’ the eyelids with a colour that enhances the natural hue of the iris. Blues and greens were early favourites. For example, Helena Rubinstein’s Valaze Eye Shadow (1928) came in Blue, Brown and Black shades, with Green added the following year.

Both ‘shadowing’ and ‘shading’ are old practices that extend back to antiquity. As the archaeologist Wallis Budge noted, black paste or powdered kohl made from galena (lead sulphide) or stibnite (antimony sulphide), and green malachite (copper carbonate hydroxide) were used as eye medicaments and cosmetics long ago in ancient Egypt.

Egyptian women soon discovered that smearing the eyelids with unguent and stibium not only eased the pain in the eyes and rested them, but also added to the natural beauty of their faces. The whiteness of the whites of the eyes was emphasized by the darkened eyelids, and the large dark pupils appeared like black pools in their midst, the whole effect being very striking. The eyebrows as well as the eyelids were frequently painted with stibium, of which several preparations were known, some wholly black and others greenish in colour.

(Wallis Budge, 1919, p. 71)

See also: Kohl

Although the practice of shadowing the eyes has a long, continuous history of use in the Middle East it is a more recent addition in Europe and the rest of the Western world. There the practice began in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as women copied make-up ideas used by stage and screen actresses.

Above: 1932 Fifi D’Orsay [1904-1983] demonstrating an old theatrical trick to create an eye shadow. A candle was used to blacken the bottom of a powder box to create lampblack which was then mixed with cold cream and spread across the eyelids.

On Western theatre stages, shading and shadowing the eyes began in earnest in the nineteenth century when brighter gas and electric stage lighting made the player’s faces more visible to the audience. On the screen, many actresses, in the first decade or so of the twentieth century, lightened their faces and shadowed their eyes to improve their appearance in early black-and-white movies.

Above: c.1921 Anita Loos [1889-1981] and her husband John Emerson [1874-1956] help the British actor Basil Sydney [1894-1968] darken the area around his eyes with greasepaint.

See also: Greasepaint and Early Movie Make-up

Exactly when shading and shadowing the eyes moved from the stage and screen into general use is unknown. However, the practice of making up at night with shadowed eyes must have been relatively common in Paris before the Great War as it was noticed by Elizabeth Arden [1878-1966] when she visited the city in 1912. It became more widespread as the use of electric lighting increased and attitudes to make-up became more relaxed. During the 1920s, eye shadowing and shading became a part of evening make-up routines for many women and this led a number of cosmetic companies to add eyeshadow to their make-up ranges. For example, Maybelline, which had been making a type of mascara since 1917, introduced its first Eye Shadow in Blue, Black, Brown and Green shades in 1929, then added a Violet shade in 1930.

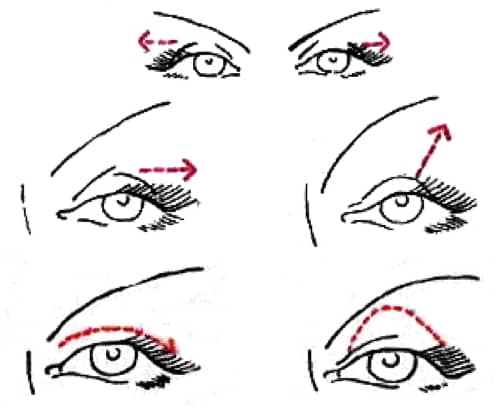

As eye shadow became more widely available and accepted, beauty experts also began offering more comprehensive advice on how best to use it.

Over and above lashes and brows, though, the beauty of the eyes can be enhanced a hundred-fold by the most discrete touch of shaded powder in their vicinity. This must be applied to the edge of the lids and just the corner of the eyes. For myself, I like for application a long strip of cottonwool wound around the top of an orange stick (one of those dedicated to manicure) until the top resembles a soft cottonwool cone. It gives sureness to the touch, and softness, so that the line of powder is easily blurred and shaded down. Only the merest hint, you must remember, is needed, and the powder must be of the right shade. For very dark blue eyes, and those of the rare violet, a blue powder does best. The more usual lighter blue would lose, instead of gain, apparent depth of colour by this, so that choice falls upon a soft grey-blue for them. The lovely dark velvety eyes, soft as a doe’s, find their salvation in a touch of brown; but when they are deepened into the mysterious depths which pass for black … the brown of the powder should deepen too, and be virtually black, but for none other; while grey and hazel eyes are beautified out of all knowledge by the judicious touch of greyish-brown powder to their surrounding.

(X. Y. Z., 1926)

Above: 1937 Yardley Rouge Cream, Lipstick and Transparent Eye Shadow, the later coming in Azure, Mist, Green-Moss and Violet shades. The sizes of the containers are an indication of how much each item of make-up was used. Most women in the 1930s would only wear eye shadow at night.

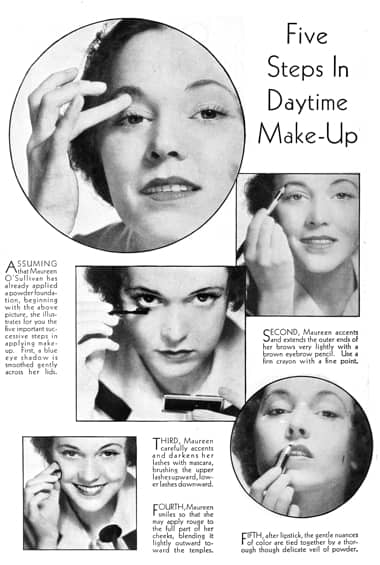

Originally seen as an evening make-up, using eye shadow during the day, along with mascara and eyeliner, became more common in the 1930s. One reason for this was a change in hat styles. When hats went off the face the exposed expanse of forehead made the eyes looks less significant. Beauty experts recommended using eye make-up, including eye shadow, to accentuate the eyes and provided advice on how best to do this.

There are two bad mistakes made in the use of eyeshadow. One is putting eyeshadow under the eyes. NEVER put eyeshadow under your eyes—only on the part of the eyelid that covers the eyeball, from corner to corner of the eyelid. . . . Smooth it on very lightly and delicately for daytime. It’s all wrong to put on eyeshadow so heavily in the daytime that people can see you coming with it. . . . But for evening, eyeshadow SHOULD be applied more heavily, and so should rouge and lipstick, because artificial lights “fade” the appearance of make-up. Therefore, to get the right effect, apply it more vividly than you would for daylight.

The other mistake about eyeshadow is the indiscriminate use of blue eyeshadow. . . .Blue eyeshadow is only for the blue-eyed and gray-eyed; but at that, I should not select blue eyeshadow for gray eyes, if your choice has to be limited to just one shade of eyeshadow. . . . An orchid or lavender shade of eyeshadow of a good brand can do much more alluring things for gray eyes—in fact, for eyes of any color. Moreover it can be worn harmoniously with clothes of any color.(Vinick, 1934, p. 71)

Cosmetic companies of the period echoed this message. The example below is from Richard Hudnut:

Above: c.1937 Richard Hudnut: How to use eye shadow.

“Today, properly used, eye shadow and mascara can play an important part in revealing the true beauty of any woman’s face. Mascara grooms your lashes, as hair tonic grooms your hair, trains them to frame your eyes in stunning beauty. And eye shadow is just that—a glamorous, half seen, half imagined background that accents color, sparkle, aliveness

Start with just a little—apply it with your finger (most girls like the little finger for this). Start the shadow directly over the center of the eyeball, just up from the fringe of eyelashes, and as close to your lashes as possible, and blend it over the lid. If your eyes are close together, be especially careful not to carry the shadow past the center of the lid towards the nose. Extend it outward to the temples, just beneath the end of the brows, or upward part way to your eyebrows, or apply it simply as a narrow strip just above the lashes.” (Richard Hudnut, c.1937, pp. 18-19)

Many cosmetic companies increased their eye shadow shade ranges in the 1930s but eye shadow was not a major seller before the Second World War and it received little attention in their advertising campaigns. This changed in the late 1950s and early 1960s as lipsticks went pale, and mascara, eyeliner and eye shadow began to be used in colourful abundance. The dramatic increase in sales led many cosmetic companies to expand their eye shadow lines and add a wider choice of eyeshadow formulations ranging from pastes, to sticks to compressed powders.

Colour and shine

As mentioned earlier, common shades in early eye shadows were black, brown, blue, green, violet and grey.

Above: 1935 Suggested eye shadow colours (France). The eye shadows appear to be relatively transparent and are only applied across the upper eyelid.

Early coloured eye shadows were generally transparent but their opacity could be adjusted by adding a white powder like titanium dioxide. This also made the colour brighter and more noticeable. Variations in the ratio of the white and coloured pigments would also determine whether the colours were truer or more pastel in shade, pastels becoming more common in the 1960s. Some formulations for eye shadow pigments from the late 1950s are given below:

Blue: 20 parts ultramarine, 10 parts titanium dioxide.

Green: 15 parts titanium dioxide, 10 parts chromium oxide green

Brown: 30 parts iron oxide (sienna shade), 3 parts titanium dioxide.In order to achieve a violet nuance, a small amount of carmine NF [a carmine lake] may be added to the blue shade. To obtain a darker blue, the ultramarine is increased and the titanium dioxide reduced.

(Wetterhahn & Slade, 1957, p. 289)

In the 1920s, eye shadows were also made to sparkle by adding finely ground metallic powders, such as silver or aluminium. There were also pearlescent forms created using crystalline fish guanine, later substituted for with bismuth oxychloride when it became available. These pearlescent eye shadows left out opacifiers as it would have masked their effect. The practice of adding glitter and/or pearlescents continued all through the intervening years before reaching a highpoint in the 1970s and 1980s largely through the introduction of new synthetic pearls.

See also: Pearl Essence

Formulations

When formulating an eye shadow, cosmetic chemists need to take two considerations, specific to eye make-up, into account. First, the skin around the eye is thin and delicate, so eye shadows need to feel smooth and soft on the skin and have less drag those used on other parts of the face. Second, eyes are very susceptible to irritants, toxins and infections. The colours used in eye shadows should therefore be completely insoluble in water and extra emphasis needs to be given to preservatives to prevent any possibility of infection.

Early eye shadow formulations were similar to those developed for rouge and, like rouge, were made in a wide variety of forms including liquids, loose powders, compact powders, pastes, creams and sticks.

Pastes

These were the commonest form of eye shadow sold before the Second World War. Made as anhydrous liquefying mixtures, they had to be firm enough to suspend the pigments used to colour them – the use of dyes being discounted – but sufficiently thixotropic to spread easily over the eyelids when applied using the little finger

Above: 1932 Applying eye shadow with the little finger.

Manufacturing would generally start with the production of a colourless base, commonly made from petrolatum, mineral oils and lanolin, stiffened with beeswax.

Eye Shadow Base

White petrolatum, short fibre soft 70.75% Cetyl alcohol 3.0 Lanolin 10.5 White beeswax 5.25 Spermaceti 10.5 (Thomssen, 1947, p. 293)

Once the base was made, it was divided with each portion mixed in a liquid state with different pigments to create a range of tints. Each shade was them passed through a heated ointment mill before being poured into plastic or metal containers. When these cooled they could be flamed to produce a smooth, attractive surface.

Over the years the formulations improved. Replacing mineral oil with isopropyl myristate made the product fell less greasy and the increased used of microcrystalline waxes, such as ceresin and ozokerite, increased the products thixotropic power, helping it to be solid in the container but liquefy under pressure when applied (Torry, 1963, p. 319).

No. 2354

Petroleum jelly 480 Liquid lanolin 40 Microcrystalline wax (m.p. 65-70°C) 80 Beeswax 40 iso-Propyl myristate 360 1000 Perfume 0.5 per cent Procedure: The ingredients are melted together and mixed. To prepare the finished eyeshadow up to 25 per cent of pigment is included, i.e. 25 parts of pigment mixed with 75 parts of the base … [A]n adjustment to the formula is necessary when dispersed pigments are used.

(Poucher, 1974, p. 291)

Paste eye shadow gave the eyelids a degree of gloss or sheen so were ideal if a lustrous film was needed. However, if less shine was desired a cosmetic chemist could tone down the gloss by adding more cetyl alcohol and/or pigment. Women could also make the eye shadow look more matt by powdering over it after it was applied.

The main problem with this type of eye shadow, or any that contain substantial quantities of waxes or oils for that matter, is that it would soon settled into the eyelid ceases and form lines, something that could only be delayed, not stopped, by powdering over it.

Emulsion creams

Although not as popular, eye shadows were also made as emulsions which were less greasy than paste forms. Maintaining the stability of the emulsion was an important consideration and the presence of water meant that preservation from bacterial contamination was more of an issue. The water was also prone to evapouration so many manufacturers elected to package these eye shadows in small tubes which were easier to keep sealed.

Emulsion-Type Eyeshadow

Stearic acid USP, triple pressed 16% Triethanolamine 4 Petrolatum, short-fiber 25 Lanolin anhydrous USP 5 Propylene glycol 5 Water 45 Pigment q.s. Procedure: Heat the waxes and the lanolin and melt at 70°C.; heat the water and the triethanolamine to the same temperature. Add the water phase slowly to the melted waxes and stir until room temperature is reached. The pigments should be ground in [through a roller mill].

(Wetterhahn & Slade, 1957, p. 290)

Sticks

Stick eye shadows, have the same advantages as lipsticks to which they are related; namely, they are convenient to carry around and apply, saving messy fingers. They were usually made softer than lipsticks to reduce their drag but, as they were generally smaller than lipsticks and applied with less pressure, they were less likely to break. This allowed a trade-off between strength and softness to be made in the formulation.

Eyeshadow Stick

(parts by weight) Mineral oil 65/75 20 Petrolatum 43/48°C 45 Carnauba wax 3 Ozokerite 78°C 10 Paraffin 68°C 4 Inorganic colors 8 Titanium dioxide 10 Procedure: Mill the inorganic pigments and titanium dioxide in a mixture of the petrolatum and mineral oil heated to about 50°C. A Morehouse mill is satisfactory. To this pigment grind, after checking (usually visually) to make certain the proper fineness of grind has been achieved, add the remaining waxes. Stir and heat at about 85°C for a minimum of 30 minutes to ensure complete melting of all the waxes. Mold while continuing to stir slowly at 75° - 80 °C. Stirring slowly while molding is required to prevent settling of pigments as well as to remove traces of air incorporated during the manufacturing of the mass.

(deNavarre, 1975, p. 727)

A variation on the stick eye shadow was the crayon. These were wider than the sticks so could be even softer which added to their popularity. Like children’s crayons they were often wrapped in peel-off paper or foil. The following formula is for a pearlescent crayon, Timica Silkwhite being a synthetic pearl.

(parts by weight) Mineral oil 65/75 45 Lantrol 7 Ozokerite 78°C 28 Inorganic pigments 5 Timica Silkwhite 15 (deNavarre, 1975, p. 730)

Pressed powders

Powdered eye shadows were made all through the twentieth century with pressed powder forms becoming more common after the Second World War. These were sold in tablets containing a range of matt and pearlised shades along with a foam-tipped applicator or brush. Like compressed face powders some were applied wet, others dry. They blended easily on the eyelid, were not as prone to forming lines in eye creases, and could be formulated to be matt or glossy, so it is easy to see why became the most popular form of eye shadow in the 1960s.

Pressed eye shadows contained talc to make them feel smooth on the delicate skin around the eyes, and metallic soaps – such as zinc stearate – to help the powder adhere to the eyelids along with colours, opacifiers and preservatives and a binder to hold everything together when it was pressed into a cake. The selection of the binder depended on whether the shadow was applied wet or dry. The formula below contains Acetulan, a proprietary lanolin derivative.

Pressed Powdered Eyeshadow

Acetulan 3% Zinc stearate USP 6 Kaolin 2 Talc, alabama 88 Magnesium carbonate 1 Pigments and titanium dioxide q.s. Procedure: Add the Acetulan to the solids that have been blended with equal potion of talc. Mix until uniform. Add the remaining talc and blend thoroughly. Micronize to insure uniformity. Press.

(Wetterhahn, 1972, p. 407)

Updated: 26th June 2019

Sources

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston, MA: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.

Jannaway, S. P. (1936). Eye cosmetics. The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record, November, 438-440.

Poucher, W. A. (1942). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (6th ed., Vol 3). New York: D. Van Nostrand Company.

Poucher, W. A. (1974). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (8th ed., Vol. 3). London: Chapman & Hall Ltd.

Richard Hudnut. (c.1937). New loveliness for you [Booklet]. USA: Author.

Rutkin, P. (1975). Eye Make-up. In G. deNavarre (Ed.). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd. ed.) (pp. 709-740). Orlando, FL: Continental Press.

Torry, L. P. (1963). Lipstick, rouge, eye make-up, manicure preparations. In H. W. Hibbott. (Ed.). Handbook of Cosmetic Science (pp. 295-239). New York: The Macmillan Company.

Wells, F. V. (1945). Ancient techniques in eye make-up still exist. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review, May, 39-40.

Wells, F. V., & Lubowe, I. I. (1964). Cosmetics and the skin. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

Vinick, N. (1934). Lessons in loveliness. Movie Classic December, 13, 71.

Wetterhahn, J. (1972). Eye makeup. In M. S. Balsam, & E. Sagarin. (Eds). Cosmetics: Science and Technology (2nd ed.) (pp. 393-422) New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Wetterhahn, J., & Slade, M. (1957). Eye makeup. In E. Sagarin. (Ed.). Cosmetics: Science and Technology (pp. 286-295). New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

Wallis Budge, E. A. (1919). The dwellers on the Nile. Chapters on the life, history, religion and literature of the ancient Egyptians. London: The Religious Tract Society.

X. Y. Z. (1926). My face is my fortune. Eve. The lady’s Pictorial, June 30, 736.

Algerian woman with eyes outlined with kohl.

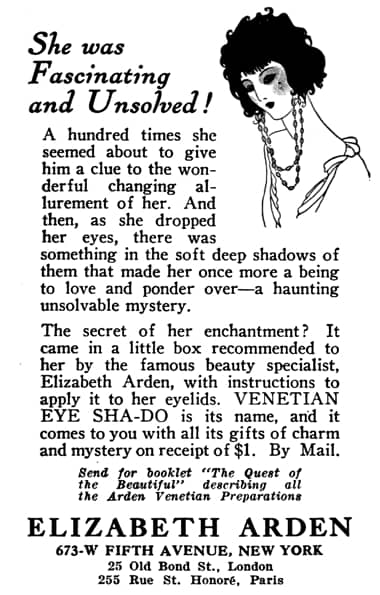

1922 Elizabeth Arden Venetian Eye Sha-Do.

1925 Louise Brooks [1906-1985] with her upper and lower lids darkened.

1930 Helena Rubinstein Valaze Eye Shadow.

1931 Max Factor [1872-1938] applying eye shadow to First National film star Loretta Young [1913-2000].

1931 Maybelline Eye Shadow.

1933 Maureen O’Sullivan’s [1911-1998] ‘Five steps in daytime make-up’ which includes applying a blue eyeshadow (Photoplay, June 1933. p. 74).

1934 Dorothy Page [1904-1961].

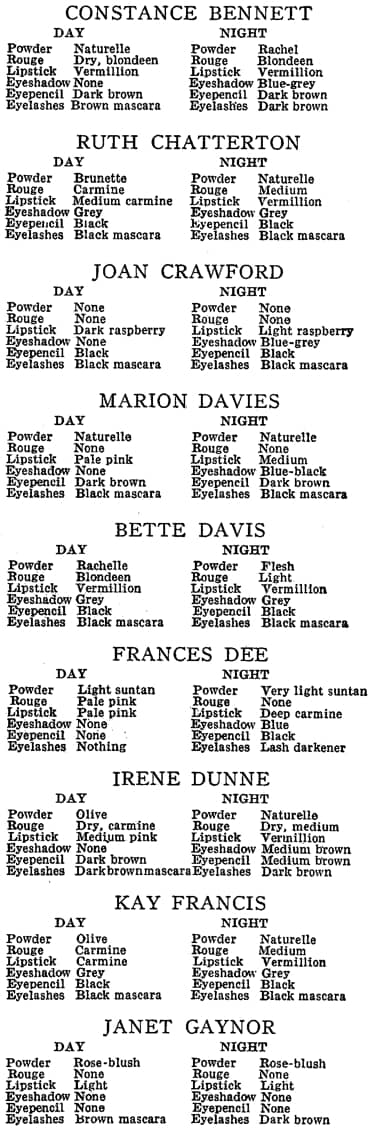

Make-up said to be worn by a range of actresses. Most are not electing to wear eye shadow during the day (Modern Screen, 1934).

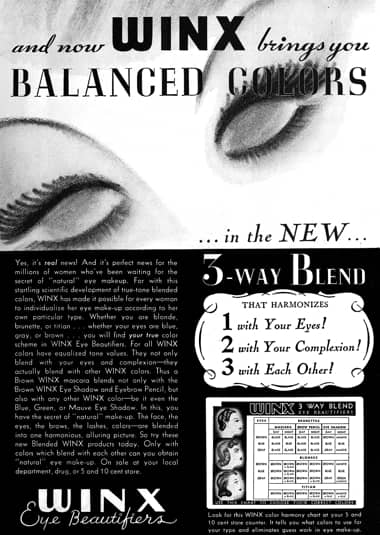

1936 Winx Mascara (Liquid and Cake) and Eye Shadow in Brown, Blue, Gray, Mauve and Green shades.

1951 Woman wearing a transparent, greenish eye glossy shadow.

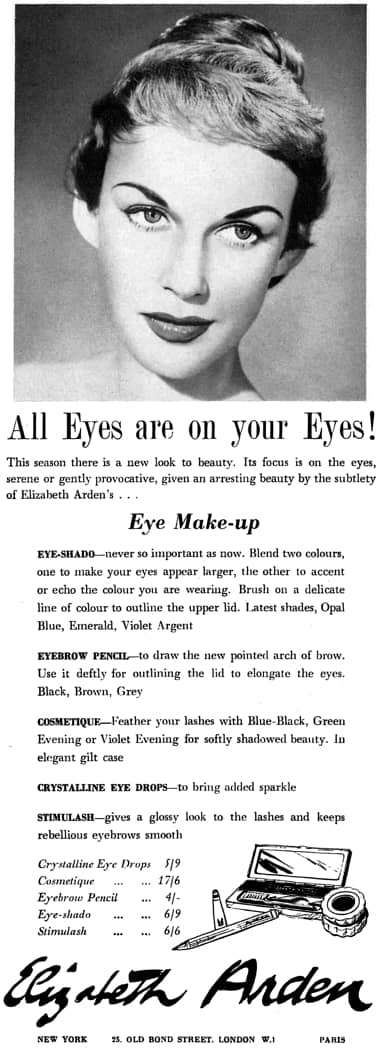

1955 Elizabeth Arden Eye Make-up which includes Eye-Shado in new Opal Blue, Emerald, and Violet Argent shades.

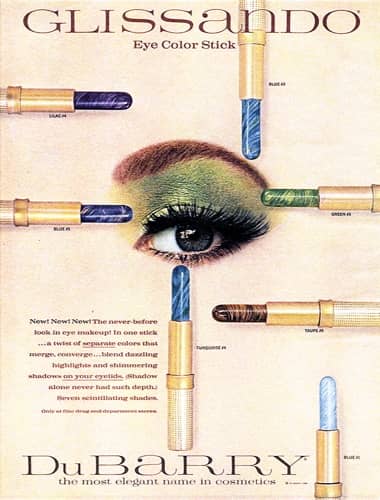

1965 Richard Hudnut Du Barry Glissando Eye Color Sticks.

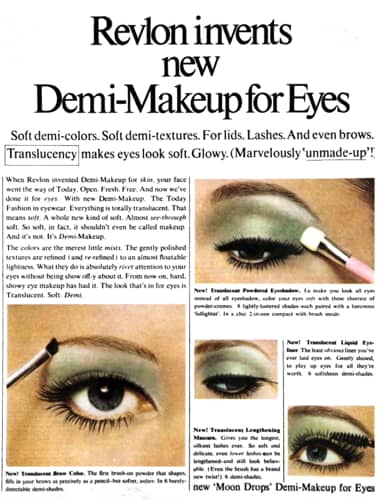

1968 Revlon Demi-Make-Up for Eyes.

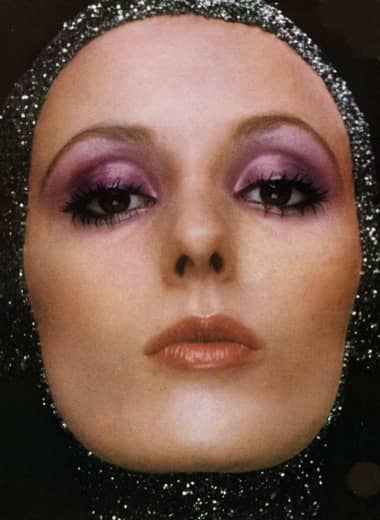

1969 Eye shadow. A return to using it on both the upper and lower eyelids.

1969 Shulton CornSilk Eye Compact.

1971 Yardley Shadow Sheen.

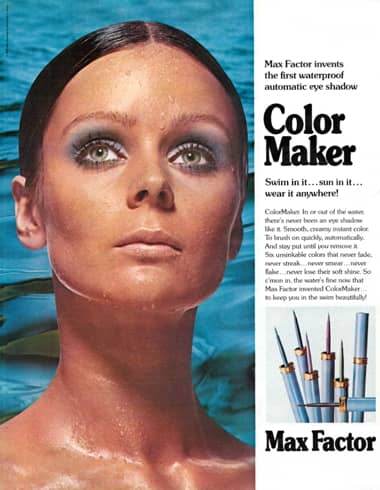

1972 Max Factor ColorMaker, a waterproof automatic eye shadow.

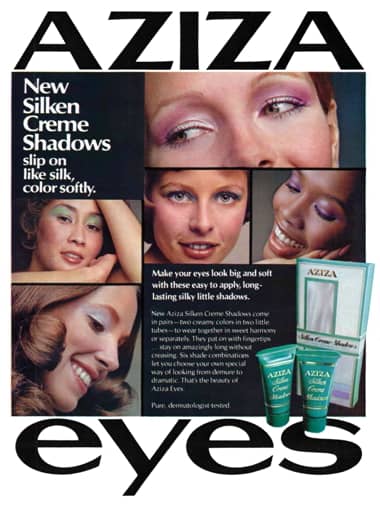

1972 Aziza Silken Creme Shadows.

1978 Cover Girl Color-Matics.