Early (Silent) Movie Make-up

The developments in movie make-up in the early twentieth century were on a scale similar to the changes that took place in nineteenth-century stage make-up after electric lighting was introduced into theatres. The motion picture industry would later develop make-up specifically for film but early screen players had to work with what was on hand. For most part this meant stage greasepaint and powder.

See also: Greasepaint

From stage to screen

Stage performers who came to work in early silent films knew how to apply greasepaint and powder but soon realised that the make-up techniques they used for the stage were generally unsuitable for the screen.

No stage artiste, no matter what his or her reputation or experience, can enter the silent drama for the first time with an all-comprehensive knowledge of the art. They must learn the limitations of the moving picture stage; they must learn to depend solely upon artistic action and not on artistic lines; they must cultivate a change in the art of make-up; and there are many other little details essential for success that must be absorbed by the stage artiste who starts to work in the silent drama.

(Dangerfield & Howard, 1921, pp. 91-92)

Early film stocks

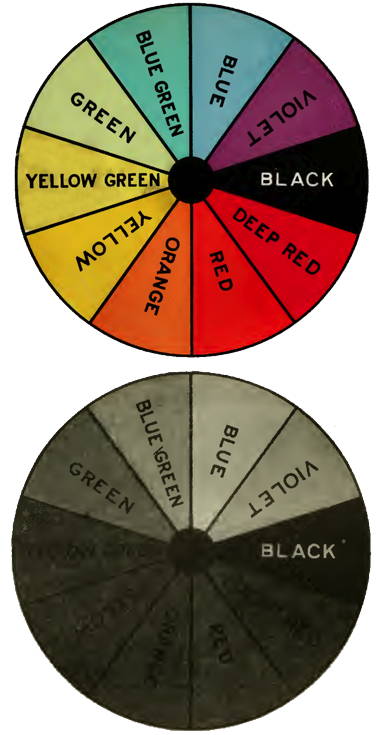

A big part of the problem with using make-up for the screen was the film stock. Until the 1920s, most black and white motion pictures were made with blue-sensitive or orthochromatic film. Blue-sensitive film was sensitive to the blue-violet end of the visible spectrum but insensitive to the yellow-red end, which meant that it registered reds and yellows as black and light blues as white. Orthochromatic film was very sensitive to violet light, markedly sensitive to blue and ultra-violet, much less sensitive to green and yellow light, and insensitive to red so had similar problems when it came to registering colours.

Labelling film stocks as blue-sensitive or orthochromatic can be problematic. For example, Eastman Standard Negative film stock, widely used in Hollywood, has been described as orthochromatic but may in fact be more correctly described as blue-sensitive as it appears to have been completely insensitive to the yellow end of the spectrum.

The problems created by these early film stocks included blonde hair photographing too dark, light-blue eyes photographing nearly white, and cloudy skies filming flat white. Moreover, as the full spectrum was not captured, grey-scale tonal differences were limited, resulting in images with a higher contrast than was visible with the naked eye. This meant that noticeable demarcations (lines) would sometimes appear on film where the naked eye only saw a gradual blend.

A skilled cameramen could ameliorate some of these problems with filters, by controlling the lighting, and by carefully selecting the locations and the colours that were to be filmed. Early cinematographers got very good at estimating what tone of grey a particular colour would look like when filmed, a task made easier when they realised that viewing a scene through a blue lens gave them a good tonal approximation (Bordwell, Staiger & Thompson, 1985, p. 283).

Skin tones

Blue-sensitive and orthochromatic film renders red as black, so unmade-up faces looked darker on the screen than they were in reality and any blotchiness in the complexion made faces look dirty. Many early film actors, particularly those that came from the stage, responded to these problems by covering their face with heavy make-up, giving them a look that belonged more on a mortician’s slab than a movie set. The practice was so common that it became almost a convention in early silent films to make the faces of heroes and heroines white while the rest of the cast, who were less made-up, looked darker.

Stage make-up is out of the question in the motion picture studio for the pinks and yellows so commonly used in getting flesh tints are distorted in color value in the film. Any tint containing red is recorded on the film at least in three shades darker than the original color, for this color has practically no actinic value. As the areas covered by the red undergo no changes due to the reduction of silver in the emulsion, the positive is printed in black under these transparent spots in the negative.

(Rathbun, 1914, p. 64)

As motion pictures became more sophisticated through the 1910s, directors began to insist on more a natural look and the mask-like faces of earlier films disappeared. This had a downside. The use of greasepaint liners and crêpe hair – used to create character or age on the stage – looked less realistic in close-ups, so directors began to select individuals for parts on the basis of their natural appearance, a practice that led to more type casting. The greasepaint liners and crêpe hair were still essential for special effects – such as when scars or wrinkles were required or when actors had to age – but they had to be used more discretely.

Lining should not be resorted to except in cases where the character of the part absolutely requires it. Lines should be made with dark red or brown and very carefully blended. Directors should take pains to select their characters according to type whenever possible and not require people to make-up out of their type unless in cases of increasing age, or effects of disease, etc., called for by the scenario.

(Gregory, 1920, p. 316)

Lighting

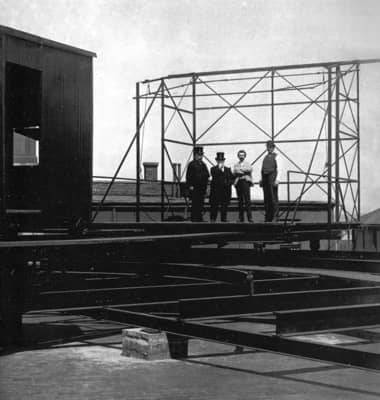

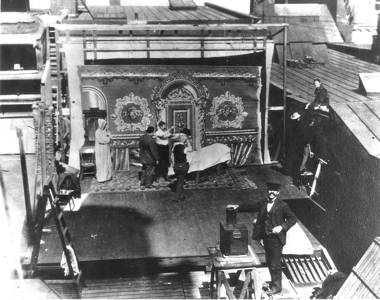

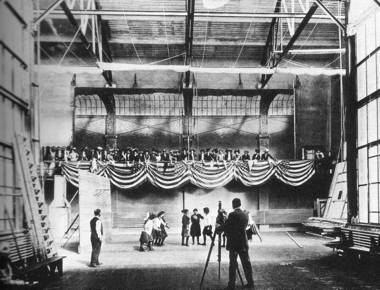

A second problem was lighting. To get sufficient light and keep costs down, early silent films were filmed in daylight, either on open stages or on location. As the movie industry developed and became more prosperous, artificial lights were introduced – first to supplement the natural light and then to replace it altogether. This freed filming from the vagaries of weather and, in the long run, gave cinematographers greater control over how their movies looked on screen.

Early film studios did not use incandescent lights of the sort used on theatre stages as they had a low actinicity – the proportion of the light which is captured on the film stock – on blue-sensitive or orthochromatic film. Instead they relied on mercury-vapour and/or carbon-arc lights. The Cooper-Hewitt mercury-vapour lamps used in American film studios produced a soft, blueish-green light that was ideal for film only sensitive to the blue end of the spectrum but made everything looked unnatural on the set. Carbon-arc lamps produced a brighter, whiter light but the light was harder and the lamps were noisy and spluttery. Early open arcs also produced arc-light dust which irritated the actor’s eyes when it got into them. Later closed arc lamps – often called ‘Klieglights’ in the United States after the Kliegl company, a major supplier – did not have this problem. However, they still caused eye problems due to the unshielded ultra-violet light they produced – the so-called ‘Klieg eye’ (actinic conjunctivitis).

Every profession has its disagreeable duties, and one of ours is to work under the studio lights. Every actress dreads them, for they are simply cruel to the eyes, and to work within a few feet of eight or ten ghastly, hissing, flaming arcs will unnerve the strongest of us. The red rays are entirely absent in these awful things, the consequence being that when they are used, everything in the scene is bathed in a sickly, bluish green. Faces appear ashen gray and the red of one’s lips looks purple. The actors appear like uncanny corpses suddenly come to life. The light is so dreadful to the eyes that the least result is a splitting headache, and the worst, the necessity of seeking the solace of an oculist or of wearing amber glasses for several days.

(Wagner, 1918, pp. 93-94)

Artificial lighting created problems for early screen actors but it also opened up new possibilities. As artificial lighting improved and the techniques for using it got more sophisticated, it become clear that it was at least as, if not more important than make-up in determining the way actors looked on the screen.

Other issues

In addition to the challenges created by lighting and film stocks, screen stars had to contend with two other developments particular to photography; the previously mentioned ‘close-up’ which revealed more detail of an actor’s face than could ever be seen from the stage; and that intangible quality, the ‘camera face’ which could determine whether they got into movies in the first place.

A camera face, or the gift of photographing pleasingly, is a great asset to a person seeking an opening in photoplay acting. Many a well-known “star” of today entered in the industry without previous experience because he or she possessed a camera face. As often as not such persons were singled out from among a crowd of “extras,” granted a tryout before the camera, and then taken in hand after proving good photographic types.

(Lescarboura, 1921, p. 44)

Unlike stage make-up – which was primarily used to strengthen facial features washed out under strong lighting – the main objective of early film make-up was to hide skin imperfections, either those that were clearly visible or the ones only apparent through the camera. Unless an actor had an absolutely flawless complexion, make-up was needed to even out their skin tone. However, in close-ups this had to be achieved without using heavy make-up.

Either heavy make-up or the close-up must go, and as I believe the close-up is due to remain an essential feature in effective motion picture photography, the players must use their make-up with an unusual degree of care. One really should be a portrait painter to obtain the correct effect.

(Dangerfield & Howard, 1921, p. 48)

A second but equally important function of early film make-up was to make the best of an actor’s facial features. Although an interesting ‘camera face’ was not essential for becoming a screen actor – acting ability was also important – it was highly desirable. When make-up specialists, like Max Factor and the Westmores, began to get involved with the American film studios in the 1920s, they transformed many famous faces to make them more pleasing when filmed.

See also: Max Factor and the House of Westmore

Greasepaint and powder

In the early days of film, some screen stars, particularly men, refused to use any form of make-up but most were eventually persuaded to do so. Individuals with a good complexion could get away with using a little cold cream covered with powder but otherwise traditional greasepaint was needed. As the demands of the screen became better understood, the greasepaint was applied more thinly and worked well into the skin so that it looked as natural as possible before powder was applied.

The basis of every make-up is a grease paint, a thin coat of which is rubbed well into the skin. … The grease paint, if put on properly, will give the skin a perfectly smooth surface of a shade slightly lighter than the grease appears in the jar. If your skin does not appear normal, except in matter of color, your grease has not been rubbed in sufficiently. Your pores should show as clearly as they normally do before you are ready to go beyond the grease paint.

(Hatton, 1922, p. 22)

Actors had to blend the greasepaint and powder to ensure that it covered the area behind the ears and the neck, and to avoid the demarcation lines and blotchiness that resulted from the greater contrast and limited spectrum sensitivity of blue-sensitive film.

Blending powders they are called, and blending powders they should be. The powder covers the entire face and is blended smoothly with the base by the slow and rather tedious process of patting it on gently but firmly with a large powder puff. Choice of color in blending powder and care in applying it is quite as important as any other part of the make-up.

(Hatton, 1922, p. 23)

The tonal shades of the greasepaint and powder used by movie actors depended on the filming conditions, the character they were playing and individual preferences. Women generally selected a lighter skin tone than men, which reflected the social norm for lighter skin in the days before suntanning became the vogue. Many actresses felt light tones also made them look younger; needless to say some overdid it.

Some actresses think that the lighter they can make themselves the more youthful they appear whereas they only succeed in making themselves look like billiard balls. A good natural flesh tint with a powdering over of flesh tinted powder to kill the gloss of grease paint cannot be improved upon.

(Gregory, 1920, p. 318)

Many screen stars believed that greasepaint restricted their facial expressions and this seems to have been one reason why some only used powder or switched to a cream greasepaint such as Max Factor’s Supreme Greasepaint or Leichner’s Greasepaint in Tubes. These could be applied thinly and felt more flexible on the skin.

Colour and tone

Early screen actors and actresses usually did their own make-up, so they had to know how they looked when photographed and how to apply it for the best effect. They also had to be able to judge the tonality of their make-up colours – to know how colour would look when converted to the black, whites and greys. Like the cinematographers they could also use blue glass to get an approximation of how their make-up would film.

In initial attempts it may help first to make up the part as though for the regular stage in ordinary tinted grease paints. Then view the effect in a mirror holding a square of bright blue glass to the eyes. This will give the effect as it would be in monochrome. You will then at once see how far to modify your methods so as to obtain the same effect in black and white for the moving picture camera. You can get blue glass from any glazier.

(‘The kinematograph and lantern weekly,’ October 31, 1912, p. 133)

Selecting make-up on its grey-scale tone, not its colour, was an art not everyone became good at it. However, with the assistance of the cameraman/cinematographer, some photographic tests and practice, most players could develop a suitable routine. Given the importance of the way they looked on screen, for some it became an obsession.

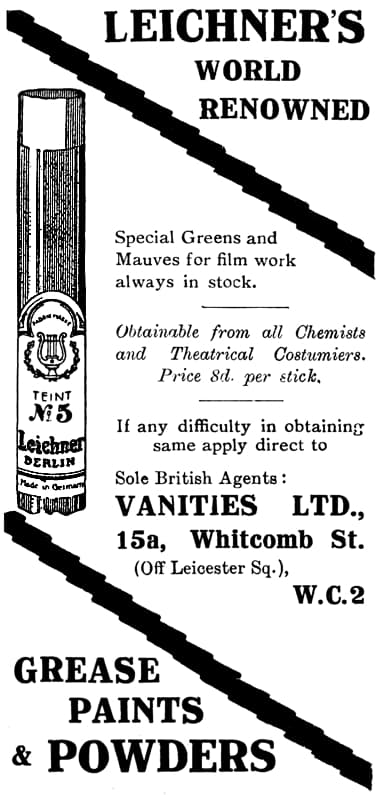

There was a lot of disagreement amongst players on how to make-up for the silent screen. Pink, more or less flesh-coloured make-up was commonly used but there was also a widespread belief that a suitable complexion could be only be produced by using yellows. A number of artists recommended using a Leichner No. 5 greasepaint or similar, sometimes used for a ‘Chinese’ make-up on the stage.

Above: 1926 Leichner Cinema Set in a tin case with mixing pallet containing 4 standard sticks and 6 liners. Leichner recommended a number of yellows, green and violet greasepaints for use when filming. These included No. 5 Chinese, the main shade used; No. 13 Red Brown for shading the hollows of the eye; No. 336 Green III to make full faces lean; No. 337 Lilac (light, dark, or extra dark, for making stout, use light powder); and No. 338 Green (for making faces lean, use yellow powder).

Also see the Leichner booklet: Artists Catalogue (1926)

In nearly all cases the face is first thoroughly whitened and then tinted with yellow so that any subsequent color that may be applied will stand out in bold relief, and also for the reason that the face will appear white instead of grey, as would be the case with the natural color of the complexion. The lips and the area surrounding the eyes are tinted with a color having a bluish cast such as heliotrope or mauve. When seen in the sunlight, the make up of the motion picture actor presents a most ghastly appearance.

(Rathbun, 1914, p. 64)

The powders used for film makeup are specially mixed for the purpose. They are yellow in color. Do not accept others. Theatrical powders are not permissible. The powders are known as Special Film No. 1 and No. 2, and are used for all grease numbers except cork for negro makeup, when a powder is not necessary.

(Leslie, 1916, p. 176)

The universal color for men is a yellow grease-paint with a slight touch of pink underneath. Blondes should be a little more yellowish than brunettes. Ladies should use a light pink or yellow with pink powder. The greasepaint must cover all blood corpuscles and freckles, which, if not properly covered, will photograph black.

(Bernique, 1916, p. 24)

If you have never had a “try-out” use a light yellow grease paint, such as Stein’s No. 27, or the Leichner Light Yellow that comes in a porcelain box, as a foundation. It is very hard to tell how a skin will look in a photograph; when I say “photograph” I mean pictures made in the glare of Klieg lights. Some skins reflect light more than others and therefore take lighter. Practical experience only will determine what is best for you. A light shade of yellow will photograph lighter than a grease paint containing pink, unless the latter has been applied to an extremely fair skin. Some skins reflect so much light that a heavier shade of grease paint is used in order that the face may be toned down to match others in the scene.

(Chalmers, 1925, p. 127)

Green or blue make-up was also suggested due to its high actinicity with blue-sensitive and othochromatic film. It may also have been easier to reconcile it under the blueish-green light of the mercury-vapour lamps.

The player with a fair complexion seldom uses grease-paint at all. He finds that cold-cream with a dash of light-brown powder screens effectively.

The player, however, possessing what I might term a medium complexion, uses either a yellow or dark-blue grease-paint after first applying cold-cream to the face, but, in order to prevent his face screening like a ball of grease, he covers it with a light-brown powder.(Dench, 1917, p. 278)

However, the use of these ‘unnatural’ colours had their critics.

Another myth that numerous actors entertain is the yellow grease-paint theory. Nobody can explain why a performer should make-up in Chinese yellow. There is absolutely no photographic theory to account for it or its use. Let the actor make-up with grease-paint if he has a rough skin but let it be flesh-colored paint, not yellow. The objections to yellow are that it is non-actinic and if the actor happens to step out of the rays of the arcs for a moment or if he is shaded from the direct force of the light by another actor his face photographs BLACK instantly.

(Gregory, 1920, p. 318)

Facial features

Make-up enabled actors to adjust their skin tone and hide skin blemishes but it could also flatten out their facial features. Rouge could not be used to highlight cheeks as, being red, it would be rendered black by the camera making the cheeks look hollow and the actor gaunt. However, as long as actors remembered which colours highlighted and which shadowed, that close-ups required a subtle hand, and to blend their make-up well, many of the tricks of facial contouring used on the stage would also work on the screen.

Consider the shape of the face. If very large, a darker shade of yellow grease paint will make it appear smaller. Regular features go a long way toward screen beauty. Bring out the oval. If your face is too broad, perhaps a narrower effect may be obtained by delicately, suggesting high light on the cheek bones a bit nearer the nose than is natural; but this must be carefully blended into the foundation. A careful blending of of all lights and shades is absolutely necessary. Always feel the formation of the bone, that is, the high light is a ridge of light on the most prominent part of the bone. Make it of some of your foundation mixed with a still lighter yellow. Have it strong enough to show through the powder. After bringing the cheek bones slightly nearer the nose, lip rouge so delicately applied that it resembles a faint pink flush can be blended down the sides of the face from temple to chin, thus shading the cheek and jawbones so that they reflect no light. Prominent jawbones so treated appear much narrower.

(Chalmers, 1925, p. 129)

Given the importance of facial expression in silent movies, eye make-up was considered essential. However, in early motion pictures it was often overdone. There was little an actor could do about the colour of their pupils if they photographed badly, but the area around the eye could be darkened with red or black to make the whites of the eyes more prominent, the eyelashes made darker with brown or black mascara and eyeliner, and the eyebrows touched up with eyebrow pencil.

The eyes are the most important and expressive features. The make-up which relates to them is all important. First you must ascertain by actual test the correct color with which to line your eyes. Almost every color is used, for the effect seems to vary with different faces. Black, blue, green, brown and red are all used in varying proportions and mixtures by different actors. Naturally, you should try to find the color which makes your eyes look deepest and most luminous.

The edge of the upper eyelid is clearly lined. Then the shade is worked back toward the eyebrow, getting constantly lighter, until it finally blends with the grease paint of the face. The process is reversed for the lower lid, which is darkest at the edge and grows lighter as you work down.

Your eyelids should be lined with black cosmetic. Do not bead them. This shows clearly in close-ups and looks rather ridiculous. The slapstick comedy people sometimes use beaded eyelids to burlesque the “baby-doll” expression.

The corners of the eyes are shadowed with brown or red. It is this shadowing that gives most of the character to the eyes; but at the same time it is apt to age the whole face. For this reason it must be done in conjunction with actual tests.(Emerson & Loos, 1921, pp. 18-19)

The space between the eyelid and the eyebrow is variously colored, the object being to bring out the white of the eye and make the latter more brilliant. Color must be considered for its utility, that is, according to the way it photographs—dark, light or medium—and not for becoming reasons; the question always uppermost in the mind should be “How can I look my best in the picture? How does this color photograph? Do I want to be dark here or light?”

A very blond person with light blue eyes should fill in this space with a grease paint that photographs dark. Brown is often chosen by blondes, sometimes red. Blur and blend it with a finger until you have a shaded portion darkest at the edge of the eyelid and fading off towards the eyebrow. Carry this blur of color out under the eyebrow beyond the corner of the eye, letting it fade into the foundation. This will immediately create contrast and prevent the white of the eyeball and the white skin of the blond appearing of the same color.

In the case of a dark-haired person with eyes of deeper blue or green or hazel, green is often used in this space. It does not photograph as dark as brown, being a mixture of yellow and blue, but it will photograph darker than blue alone. A decided brunette can use blue. Should the space be large, purple is possible for the reason that, being made of blue and red mixed, it becomes positive and prints a darker gray than pure blue. A very light blue washes out entirely just as the photograph of a girl in a light blue dress will reproduce the color as white.

If the eye is very large and black with a heavy dark eyebrow hanging close over it, no coloring is needed in this space.(Chalmers, 1925, pp. 130-131)

Like rouge, lipstick is red and therefore photographs black on blue-sensitive and orthochromatic film, so it had to be avoided or used sparingly. Some actresses painted their lips very dark but a light colour was more generally used and/or the lipstick was applied very lightly. Men would use a greasepaint on their lips that was similar to what they were using on the rest of their skin and try to make sure that the outline of their mouth was visible.

Be very sparing in the use of lip rouge. Remember that red photographs black and that a heavy application of rouge shows an unnaturally black mouth on the screen. Except in very rare cases do not attempt to alter the shape of the lips by the application of lip rouge. It almost invariably shows.

(Gregory, 1920, p. 316)

We’ve all noticed and some of us wonder why it has to be, that nearly all movie heroines have black lips. Just so long as the women of the films persist in coating their lips with rouge, just so much longer must we wait for the perfect film. If you must paint your lips (because to you they look so alluring in the mirror), choose a very light shade of red, shape your lips perfectly, then with a towel press gently until their centers hold scarcely any paint. Glycerine applied over the lip rouge makes the lips appear not only shiny, but more prominent.

(Chalmers, 1925, p. 131)

Make-up specialists

By the 1920s, most experienced actors understood the limitations of using make-up when working in film. In case they did not, the studios began to put out pamphlets and leaflets on the subject to ensure that the worst mistakes were not repeated.

Leads still largely did their own make-up but studios increasingly began to refer new-comers to a make-up specialist for advice. Specialists also began to be employed to make-up the extras and others who could not be trusted to go it alone. Some of these make-up artists would go on to work in the permanent make-up departments later established by the studios.

Above: 1916 Richard Leslie [c.1883-?] applying make-up to extras on a Vitagraph fim set. He had been made Make-up Manager for Vitagraph five years earlier.

When the first make-up department was established in Hollywood is an open question. George Westmore [1879-1931] is generally given credit for this at Selig Polyscope studios in 1917. However, McLean has convincingly argued that this is untrue, given that the Westmores did not arrive in Los Angeles until 1920 and Selig ceased movie production in 1918 (McLean, 2022, p. 70).

New film stocks

When the movie industry converted to panchromatic film in the late 1920s the earlier make-up rules had to be abandoned. In Hollywood, the studios looked to specialists like Max Factor to help solve the make-up problems generated by the change in film stock and the switch to incandescent lighting necessitated by the introduction of sound. The make-up developed for panchromatic film by Max Factor and others required screen players to change the way they made up for filming. By now this was becoming increasingly controlled by studio make-up departments.

See also: Panchromatic Make-up

First Posted: 17th February 2013

Last Update: 22nd January 2023

Sources

Basten, F. E. (1995). Max Factor’s Hollywood. Glamour, movies, make-up. Los Angeles: General Publishing Group.

Bernique, J. (1916). Motion picture acting for professionals and amateurs a technical treatise on make-up, costumes and expression. Producers Service Company.

Bordwell, D. Staiger, J., & Thompson, K. (1985). The classical Hollywood cinema. Film style & mode of production to 1960. New York: Columbia University Press.

Brownlow. K. (1968). The parade’s gone by. New York: University of California Press.

Brownlow. K. (1979). Hollywood: The pioneers. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Chalmers. H. (1925). The art of make-up, for the stage, the screen, and social use. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Clarkson, W. (1918). The art of screen make-up. The Bioscope October, 24, p. 95.

Dangerfield, F., & Howard, N. (1921). How to become a film artiste. The art of photo-play acting. London: Odhams Press Ltd.

Dench, E. A. (1917). Motion picture education. Cincinnati: The Standard Publishing Company.

Eastman Kodak Co. (1919). The photography of colored objects (3rd ed.). Rochester, NY: Author.

Emerson, J., & Loos, A. (1921). Breaking into the movies. New York: James A. McCann company.

Gregory, C. L. (Ed.). (1920). A condensed course in motion picture photography. New York: New York Institute of Photography.

Handley, C. W. (1954). History of motion-picture studio lighting. In R. Fielding (Ed.). (1967). A technological history of motion pictures and television: An anthology from the pages of the journal of the society of motion picture and television engineers. (pp.120-124). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hatton, R. (1922). Making up for the screen. In Photoplay Research Society. Opportunities in the motion picture industry. Los Angeles: Author.

Lescarboura, A. C. (1921). Behind the motion picture screen (2nd ed.). New York: Scientific American Publishing Company.

Leslie, R. (1916). The art of make-up. Motion Picture Classic. October, 22-24.

McLean, A. L. (2022). All for beauty: Makeup and hairdressing in Hollywood’s studio era. New Brunswick, Camden: Ruters University Press.

Mees, C. E. K. (1954). History of professional black-and-white motion-picture film. In R. Fielding (Ed.). (1967). A technological history of motion pictures and television: An anthology from the pages of the journal of the society of motion picture and television engineers. (pp. 125-128). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rathbun, J. B. (1914). Motion picture making and exhibiting. Chicago: Charles C. Thompson Company.

Redgrove, H. S., & Foan, G. A. (1930). Paint, powder and patches: A handbook of make-up for stage and carnival. London: William Heinemann.

Wagner, R. (1918). Film Folk. The Century Company.

A representation of the difference between blue-sensitive film and modern colour film. Note how the sky looks washed out and clouds do not show up. (Modified from an image created by Peter Patau).

Colour charts to represent how blue-sensitive film registers colour in shades of grey (Modified from Eastman Kodak Co., 1919).

Cinematographer Joseph LaShelle [1900-1989] wearing a blue glass filter around his neck to help him judge the tonal effect of colours. Cameramen frequently used some form of blue glass filter to help them judge how blue-sensitive film would record a scene. When viewed through the glass the scene was reduced almost to a monotone, and reds and greens appeared dark. In extreme cases it was not accurate, as blue-sensitive film is sensitive to ultra-violet light which the human eye cannot see.

The actress is Colleen Moore, a.k.a Kathleen Morrison, [1899-1988]. She had heterochromia (one brown and one blue eye) and before she was given a studio contract a test film was made at Essanay Studios to see how they photographed on orthochromatic film. The test revealed that her left and right eye looked slightly different on film but it was not obvious so she was given a contract with Triangle-Fine Arts.

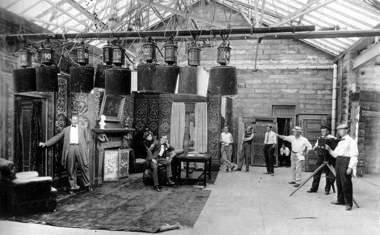

1896 American Mutoscope and Biograph Company erecting a rotating stage that can follow the sun on the top of the Hackett-Carhart Building in New York.

1899 A dressed, open-air set on the roof of the Lubin Studio in Philadelphia. Shadows from surrounding buildings could prove to be a problem.

The Selig Polyscope Company in Chicago showing the ‘glass house’ on top of a building used to film in daylight.

1908 Edison Studio using natural lighting controlled by screens.

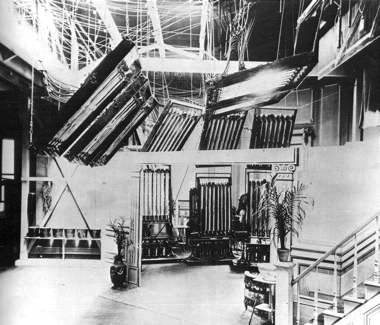

1910 Vitagraph film studio using Aristo arc lights to supplement natural daylight. Lights this close would have been extremely hot to work under.

A Lubin Company film studio around 1911 using natural light. As the films were silent a number of movies could be made along side each other.

1911 Edison film studio using overhead arc lights.

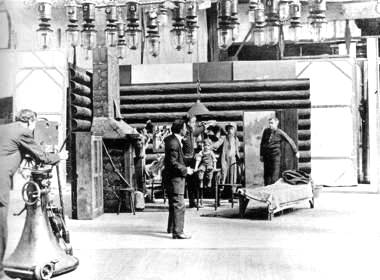

1912 Make-up on a D. W. Griffith picture. Note the tonal differences between the lead male actor (seated centre), the technician in the straw boater hat (who is not wearing make-up), and the other members of the cast.

1913 Spectrum Film Producing Company, London. Panchromatic film stocks were available in the 1910s but they were not widely used until the late 1920s.

1914 Biograph film studio showing Cooper-Hewitt mercury-vapour lights. These lights were often only a few feet away from the actors.

1914 The Squaw Man. The difference between a lead and an extra can be seen in this image. The make-up worn by Dustin Farnum [1874-1929] (front) gives him a mask-like look. Grey-scale tonal differences were limited in blue-sensitive film but Thompson has suggested that this impression is overstated because the old silent films we see were created from positive prints rather than from original negatives (Bordwell, Staiger & Thompson, 1985, p. 281). If this is correct then some of the mask-like appearance of this lead actor would not have been as noticeable when the film was originally screened.

Earle Williams [1880-1927] in ‘His Phantom Sweetheart’ (Vitagraph, 1915) wearing a lot of eye make-up.

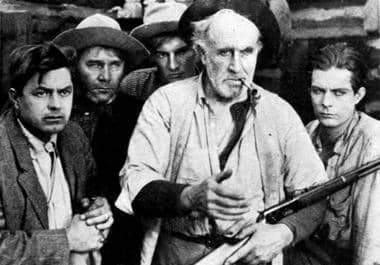

A range of make-up styles used by different actors in ‘The Trail of the Lonesome Pine’ (Laskey Photoplay Company, 1916).

A make-up man using stick greasepaint at Universal Studios (Wagner, 1918).

William ‘Willy’ Clarkson [1861-1934], a well-known London theatrical costumier and wigmaker discusses screen make-up.

“In making up for the camera it is essential to remember in the first place that the conditions to be considered are utterly different from, and in many respects opposed to, those of the theatre. The poor results obtained with make-up by artists in the early days of the screen play were entirely due to ignorance of this difference and neglect to submit the demands of the camera to a scientific analysis. The theory that it is impossible to employ make-up in acting for the camera is pure fallacy. Make-up may be used as extensively in the studio as on the stage, but it must be used differently and with even greater skill and precision.

One of the rudimentary necessities of making-up for the screen is the complete avoidance of red—in lips, in cheeks, in clothes—in fact, anywhere. Rouge or lip salve must never be employed; they produce a hideous negroid black. The usual tints for an ordinary straight make-up on the screen are 5 or 5½—that is to say, equivalent make-up for a Chinaman on the stage. Grey should be used for lips in place of carmine and also above the eyelids. Children are paled and sallowed because the healthy, fresh complexion of a child photographs a heavy black.

It must never be forgotten that it is the effect as reproduced by the camera, and not as seen by the human eye, that is the test. Some producers, such as Mr. Thomas Bentley, insist upon reviewing the make-up of their artists through the lens of the camera before finally passing them. This method often reveals otherwise undiscernible faults of detail, such as the gumming-up of a moustache, which may take half an hour to adjust accurately.

Wigs for the screen differ from wigs for the stage inasmuch as the latter all have ‘temples,’ whereas in the former case the join, however carefully plastered, would always become visible on the film. Screen wigs are therefore always specially cut, and never protrude beyond the natural hair.

The ear is an important but often neglected detail, through which the whole character of the face may be accentuated or altered. By colouring the lobe of the ear facial defects may be considerably modified—a point carefully studied by French actresses, including Sarah Bernhardt.

Many have wondered how the faithful representations on the screen of well-known historical personages have been accomplished. It is done in the following way: A large company of competent actors are engaged on trial. These are studied by myself or my assistant. We choose the type of face which contains the essential features that cannot be wholly manufactured, but which serve as a basis for working upon. We then proceed to alter and complete the minor features with paste, paint, and sometimes a false part, to secure the necessary likeness.

There is no doubt about it, British productions have beaten American in the question of make-up and costume. The Americans rely upon broad effects and masses of players, but here we have made personal appearance a fine art. You may generally take it for granted that the costumes and settings employed in any period film by a recognised British company are historically accurate.” (Clarkson, 1918, p. 95).

Frank Hall Crane [1873–1948] with his opinion on the best make-up for the screen.

“I have experimented with many different tones of grease paint and powder to get natural results on the screen, but have settled on 1½ paint and a light pink powder as the make-up most satisfactory for general purposes. Many directors use this combination and agree with me that it cannot be beaten. This make-up supplied by the producing company, should be used by the entire cast to get a general uniform effect. The paint should be of one make and from one manufacturer, while the powder should be mixed in large quantities at the studio. I always mix it myself, using a heavy mortar and pestle to grind it as fine as possible. The make-up for both exterior and and interior scenes should be the same.” (‘The kinematograph weekly,’ September 30, 1922, p. 57)

Raymond William Hatton [1887-1971], a character actor, gives his views on applying make-up colours.

“For a straight character I use a number five, which I can best describe as a rather light brownish-yellow.

… Above my eyes, in straight make-up, I use a thin, smooth shading of brown. My eyelids are lined with the same color. Many players prefer black for the eyes and never vary from it, but it has been my experience that the brown gives a much softer screen tone which is far more desirable. This again is a matter of personal preference as well as a matter that depends on the natural coloring of the individual, and there can be no set rule.

Many players, even the most experienced, I think, ruin what is otherwise a perfectly splendid make-up by using too heavy color on the lips. My preference is for a rather light red and I use an extremely thin coat of that. In fact, the grease on my lips does little more than accentuate the natural shape of the mouth. The resultant screen tone is a soft dark gray, that suggests the real color of one’s lips much more accurately than the hideous black so often seen on the screen. The black, of course, comes from too heavy a coat of too dark a red and is something you should be careful to avoid.

Last, and entirely as important as any other feature of the make-up, is the powder. My powder is a shade that corresponds to the number five paint.

… Generally speaking, women use lighter make-up than men. Mrs. Hatton uses a number two grease paint, which is about the average for women in straight make-up, although women must vary their shades of grease with type the same as men. Mrs. Hatton has found after much experimenting that a blend of this number two grease paint with a number seven powder quite dark gives the best possible results. Her make-up for her mouth and eyes is quite like mine.” (Hatton, 1922, pp. 22-24).

1922 Pola Negri [1897-1987] applying make-up. She appears to be using a palette of four colours and applying them with a brush. There is a greasepaint stick next to the basin.

1922 Leichner Special Greens and Mauves for film work (Britain). Leichner referred to No. 5 (Chinese) as its Principal Cinema Shade.

Make-up comparison showing how to make-up for black and white and colour films. There were a number of experiments with colour film systems through the early part of the twentieth century. Unfortunately, I do not know the type of colour film stock this make-up was designed for. Given the make-up colours used for the black and white make-up it would appear that the suggested black and white make-up is for blue-sensitive or orthochromatic film.

1927 Makeup artist Jack Dawn [1892-1961] trimming the sideburns of the actor Tim McCoy [1891-1978] during the filming of California (MGM, 1927).

Max Factor’s Supreme Greasepaint packed in hygienic green tubes.