Queen Alexandra and Face Enameling

The death of Queen Victoria in 1901 ushered in the Edwardian age, with Alexandra of Denmark – who was 57 at the time – becoming queen-empress consort to King Edward VII in 1902. Edward was to die only eight years later in 1910. Alexandra – known as Alix to those close to her – supported Edward during his short reign, as she had done during the long period when he was the Prince of Wales. Edward made a number of questionable choices in his life but it was generally agreed that his decision to marry Alexandra was one of his better ones. Of her many assets, her beauty and grace were foremost in people‘s minds.

Bertie from the first was most anxious to fulfil all kinds of public engagements as Prince of Wales, and here, of course, he looked to Alix to support him. Her wonderful beauty and grace were a tremendous asset to him in such work, and however boring the work in hand he always felt inspired when she was with him and said the right thing to everybody and was affable to the right people.

(Tisdall, 1954, p. 60)

When the First World War ended in 1918, Alexandra was nearly 74 years of age. As the mother of King George V she still engaged in public appearances but – presumably to maintain her reputation as a beauty – took to wearing veils, wigs and apparently resorted to having her face ‘enameled’. Photographs of her were also doctored to remove wrinkles and other signs of ageing.

Alexandra was no stranger to being concerned about her appearance. The high chokers she made fashionable were apparently worn to cover up a childhood scar she had sustained on her neck and, like many women of her time, she probably used hairpieces (before resorting to a wig) to bulk up her hair under the huge hats popular in the period. Although the use of skin-whitening cosmetics was not uncommon, the source of Alexandra’s well-preserved appearance created a considerable amount of conjecture.

Among the younger postwar people, mention of Queen Alexandra used to be made with bated breath: they whispered of a fabulous woman like Rider Haggard’s She, incredibly old, with the beauty of a girl.

(Tisdall, 1954, p. 302)

Even if Alexandra did not ‘enamel’ her face, her use of cosmetics and other beauty aids sent a signal of approval to the members of the court and the wider public that may have helped make Beauty Culture more respectable.

Queen Alexandra was undoubtedly responsible for the stationary age edict; to the end of her days she was never old. Her slender neck, tightly collared, was stiffly upheld, to bow only at the approach of illness. Her cheeks were faintly pink and her hair acurl in a pointed peak upon a scarcely wrinkled forehead. Massage and cream, cosmetics and powder were constantly used by her attendants. The bonnet was taboo, the toque exalted—and the results remarkable. All England followed her lead; faces and figures were preserved, baldness banished and hair artistically replaced when necessary. The old women were extinct by order, precept and practice.

(Britannia, 1928, p. 68)

Enameling

The process is a form of face painting, the main aim being to achieve the look of younger, whiter skin. This was accomplished by applying a white base, followed by rouge for ‘rosy’ cheeks. Thin blue lines were sometimes added to mimick superficial blood vessels thereby giving the skin the appearance of translucency. It is probable that there were variations in how the process was done. Alexandra was reputed to have preferred an overall pink look.

In enameling the face, the skin is first prepared by an alkaline wash, after which all wrinkles and depressions are filled with a yielding paste. Then the face is simply painted, and artists in this line generally prefer to use the poisonous salts of lead for the purpose, as they produce more striking effects than any other pigment. After the white layer is applied, the red tinting is done.

(Butterick, 1892, p. 234)

It is hard to know how widespread the practice of ‘enameling’ was during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Leaving aside chorus girls, courtesans and other women of ‘ill repute’, it is possible that the practice was used by some older upper class women, was generally avoided by the middle classes, and not practiced at all by respectable, young, unmarried women. Social commentators generally disapproved of it.

The process of enameling is not to be recommended, as the ‘enamel’ must clog the pores of the skin for the time it remains upon the face; and besides it renders necessary perfect repose of the features, so that emotions, whether happy or sorrowful, must be repressed, thus giving a monotonous semi-melancholy expression to the face which cannot prove attractive and, owing to the cause, often occasions sarcastic criticism.

(Butterick, 1892, p. 234)

The salacious nature of the practice meant that it had a fascination that doubtless led to exaggeration; filling wrinkles and depressions with yielding paste being one of them.

A word about “enameling” the face.

There has been such a noise in the newspapers of recent years about “enameling” the face, that we are in duty bound to say a word about it. The most absurd stories are afloat. One we noticed asserted that the late actress, Madame Vestris, was obliged to sit “hours” by the fire to allow her “enamel” to dry. Another stated that certain New York belles visit Paris annually to have their complexions “made up” for the year. An enterprising rascal, taking advantage of popular credulity, advertises in various papers to enamel faces “to last a day or a year.”

Such paragraphs arise from ignorance. The so-called method of “enameling” is simply painting the face, and for this purpose the artists always prefer the poisonous salts of lead, as they yield much more striking effects. Practice often gives these persons a decided skill in their specialty, but their customers pay for it doubly, first in money and then in health.

The skin is usually prepared by an alkaline wash, wrinkles and depressions are filled with a yielding paste, and the colors are laid on to the requisite extent, first the white and then the red.

No such procedure can give a durable covering to the face, and no one should submit herself to the hands of the ignorant and unscrupulous parties who choose this for a business. The simple and harmless means which we have explained will suffice, if skilfully used, to conceal the ravages of years to any proper extent.(Brinton & Napheys, 1870, pp. 214-215)

Then there were those that did not think that it ever occurred.

Enameling the face and neck is impossible; it never has and never can be done. The reason that certain ladies, not excepting the most illustrious in the land, are stated to have been enameled, is because every woman, from the highest to the lowest, is exposed to the malevolent tongue of malice, slander and scandal. The slender base on which these rumours rest is the mere fact that in some books receipts have appeared under the headings, “Massage Enamel” and “Liquid Enamel,” and that in some case the preparations contain bismuth salts and other metallic preparations.

(Potter, 1908, p. 134)

Composition

A number of cosmetic companies had an émail or enamel in their product line. Marie Earle for example sold Émail 77 and Helena Rubinstein marketed Email du Visage. The description below is from a London firm.

Venetian Face Enamel.

This preparation has been swift to secure favour, and it can be relied upon absolutely to do what is required of it. It is a velvety substance, which, if applied to the face, neck or arms, will cover up blemishes and impurities on the skin, also redness, roughness, freckles and sunburn. It does not cure, but is a temporary and instant means of producing a fresh looking, spotless complexion, which is irresistibly attractive. Full directions for use accompany each bottle.(Bayard, Vane & Co, 1893, p. 31)

See also: Marie Earle and Helena Rubinstein

The composition of enamels varied and covered both liquid and cream preparations many of which could also be called liquid powders or liquid pearl powders.

See also: Pearl Powders and Liquid Face Powders

Those who were critical of enameling describe it as being “white lead in a cream base”. However, the harmful effects of lead were well known by the late nineteenth century, so zinc oxide or bismuth salts (bismuth oxychloride or bismuth subnitrate) were widely used as the whitening agent instead, bismuth subnitrate described by Durvelle as enamel white (Durvelle, 1923). The recipes below use a range of whites:

A preparation for whitening the face and neck, reputed to be most excellent, is made as follows:

Turpentine 3 grains. Oil of sweet almonds 4 ounces. Spermaceti 2 drachms. Flour of Zinc 1 drachm. White wax 2 drachms. Rose-water 6 drachms. Mix the ingredients in a water bath, and melt together. Zinc is generally considered a harmless mineral-white, and is often used in preparing healing ointments. It becomes fixed in the unguent or cream just mentioned and is thus easily applied. The preparation is a sort of enamel which does not need the baking so many people think necessary to professional enameling.

(Butterick, 1892, p. 234)

Enamels for the Face

According to “Beasley” this is one of the best formulae, and very closely resembles the so-called French enamels.

Freshly precipitated moist zinc oxyhydrate

(containing about 20 per cent.)1 oz. Glycerine 10 min. Concentrated essence of Trefle blanc. 4 min. This, when spread on the skin, leaves a semi-transparent film or enamel. It is infinitely superior to the ordinary zinc oxide or calamine lotion, which are quite coarse compared with the oxyhydrate.

The following are the perfumes used:—

Concentrated lilac essence 4 min. to each oz.

Concentrated violet essence 4 min. to each oz.

Concentrated white rose essence 4 min. to each oz.

Concentrated chypre essence 4 min. to each oz.(The Hairdresser and Beauty Trade, 1913, July, p. 1123)

Liquid Enamel.—Liquid enamels occupy a place midway between toilet powders and lotions. They vary considerably in cost. The better class are made with bismuth oxychloride, the cheaper with zinc oxide.

Take of

Bismuth oxychloride ¾ oz. Glycerin 2 fl.drms. Concentrated extract of violet (500) 5 drops Rose water to produce 2 fl. ozs. Take of

Zinc oxide ½ oz. Whitest talc ¼ oz. Eau de Cologne oils 7 drops Glycerin 2 fl. drms. Distilled water to produce 2 fl. ozs. If tinted enamels are required a trace of the tinting ingredients described under toilet powders may be added. Carmine, eosin or alloxan are sometimes recommended, but are not satisfactory. The skin is yellow, not pink or violet.

(Lucas, 1914, p. 282)

Recipes for the blue pigment used to paint the blue veins were also available. Applying these would have required a good deal of skill.

L’eu Végetal Pour Les Veines.

Venetian chalk 1 lb. Berlin blue 1¾ oz. Gum acacia 1 oz. To the powdered solids add sufficient water to form a mass to be rolled into sticks. For use, a pencil is breathed on, rubbed against the rough side of a piece of white glove leather, and the veins are marked with the adhering color on the skin coated with pearl white. Of course, some dexterity is required to make the veins appear natural by the use of this blue color.

(Askinson, 1923, p. 301)

Why the process was called enameling is unclear. The term seems to have arisen early in the nineteenth century to describe the application of “certain preparations to the face in order to impart the appearance of smoothness to the skin” (OED). Most likely, the word ‘enamel’ simply meant ‘paint’. The use of these words has changed over time and both have been replaced with the term ‘make-up’.

First Posted: 18th May 2009

Last Update: 23rd October 2022

Sources

Askinson, G. W. (1923). Perfumes and cosmetics their preparation and manufacture. A complete and practical treatise for the use of the perfumer and cosmetic manufacturer covering the origin and selection of essential oils and other perfume materials, the compounding of perfumes and the perfuming of cosmetics, etc. London: Crosby Lockwood and Son.

Bayard, Vane & Co. (1893). Beauty culture: What dermatology has to do with beauty. London: Author.

Brinton, D. G., & Napheys, G. H. (1870). Personal Beauty: How to cultivate and preserve it in accordance with the laws of health. Springfield, Mass: W. J. Holland.

Butterick Publishing Company. (1892). Beauty its attainment and preservation (2nd ed.). New York: Author.

Clark, F. M. (1883). Analysis of certain cosmetics. Proceedings of the Convention of Druggists and of the First Annual Meeting of the Michigan State Pharmaceutical Association. 156-157.

Cooley, A. J. (1866). The toilet and cosmetic arts in ancient and modern times with a review of the different theories of beauty and copious allied information social, hygienic, medical. New York: Burt Franklin.

Ellington, G. (1869). The women of New York or the under-world of the great city. Illustrating the life of women of fashion, women of pleasure, actresses and ballet girls, saloon girls, pickpockets and shoplifters, artists’ female models, women-of-the-town, etc., etc., etc. New York: New York Book Company.

Gunn, F. (1973). The artificial face: A history of cosmetics. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles.

The hairdresser and beauty trade. (1913). London.

Lucas, E. W. (1914). Toilet powders and lotions. Perfumery and Essential Oil Record. July, 283.

The old woman grumbles by Aunt Eliza. (1928). Britannia. 1(1) 68.

Potter, C. B. (1908). The secrets of beauty & mysteries of health. Being practical suggestions for the right care of the person together with a collection of valuable receipts pertaining to the health & beauty gathered during the author’s stage experiences & travels in all parts of the world. San Francisco: Paul Elder and Company.

Tisdall, E. E. P. (1954). Alexandra: Edward VII’s unpredictable queen. New York: John Day Company.

Queen Alexandra [1844-1925] (right) with her mother (centre) and eldest daughter, Princess Louise (left).

1902 Queen Alexandra’s coronation photograph untouched. She would have been about 56 years of age when this photograph was taken.

1902 Queen Alexandra’s coronation photograph retouched, to make her look much younger.

1923 Queen Alexandra, aged about 79, made up to look much younger than her age would suggest.

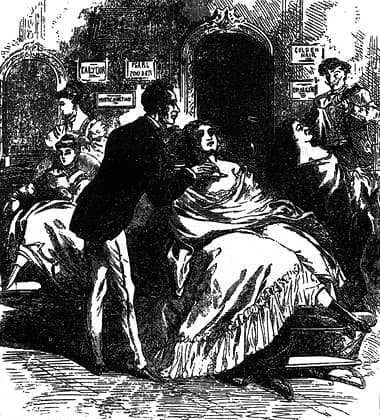

False faces—An enameling studio on Broadway

“Painting the face, shoulders, neck and arms is indulged in to a considerable extent by New York ladies. Indeed, there are regular enameling establishments in the city, one of which advertises to put it on so that it will stay for a year. We fancy this is stretching the matter a little, but the very idea is horrible. Imagine a lady going a whole year without washing her face! …

The business is carried on by a chiropodist of Broadway. Our illustration represents a scene in this “enameling studio.” The process may be described as follows: The lady is first carefully examined with a microscope, and any rough hairs or fuzz which exist upon the cheek or bust are at once removed with liniment or plaster, medicated soap, scissors or tweezers. The cheeks or bust are then coated with a fine enamel, which is composed of arsenic or white lead and other ingredients made into a semi-paste. An ordinary coating will last for a day or two, but to render the operation of permanent value, the process must be repeated once or twice a week.

The prices of enameling vary, but average about as follows: For enameling the face to last once or twice, from ten to fifteen dollars; for enameling the face and bust temporarily, from fifteen to twenty dollars; for enameling the face to endure one or two weeks, from fifteen to twenty-five dollars; for enameling the face and bust to last about the same period, from twenty-five to thirty-five dollars; for keeping the face for six months in an enameled condition, from two hundred to three hundred and fifty dollars; for keeping the face and bust in the same state for the same length of time, from four hundred to six hundred dollars.”

(Ellington, 1869, pp. 84-85)

1864 Hunt’s White Liquid Enamel.

1866 Chastella’s White Liquid Enamel.

1883 Hagan’s Magnolia Balm. This product, which is basically a calamine lotion, was regarded by some as an enamel.

1885 Hunt’s White French Skin Enamel.

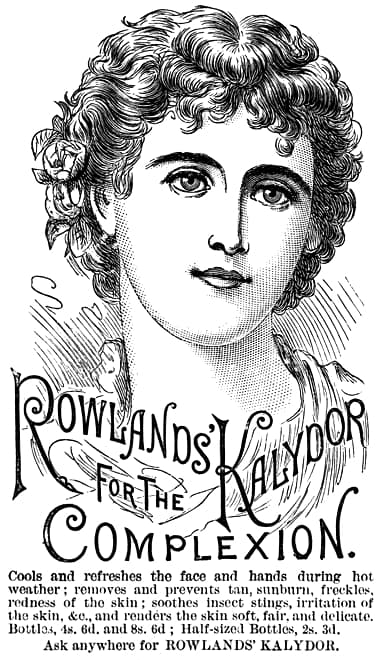

1887 Rowland’s Kalydor.