Pearl Powders

Powdered pearl has a long history of use in face and body powders. Pearls are usually white or bluish-grey in colour, with a fine lustre and, being expensive to own, highly sort after. Chemically, they are made up of layers of aragonite (a form of calcium carbonate) held together by the protein conchiolin. This substance forms a soft, fine, white powder when ground.

The practice of powdering pearls for use in cosmetics may have started in China where it continues to this day. The pearl used was most likely garnered from fresh-water molluscs rather than the more expensive salt-water oysters. There were also versions made from the mother-of-pearl from the nacreous internal lining of shells. After being made in the East, the powders made their way to Europe to become one of many exotic materials found in well stocked apothecaries, sold separately or in cosmetic kits.

Pearl Powder. Of these powders there are several sorts; the first and finest is a magistery made from real pearls, and is the least hurtful to the skin. It gives the most beautiful appearance, but is usually too dear for common sale or use: still the good perfumer ought never to be without it, for the use of the curious and the rich.

Imitated by other kinds of powder, some of which are made from mother of pearl, and some from oyster-shells; but, as the magistery made from these is never so impalpably fine as the former, they leave a shining appearance on the face, which shows the art that has been used on the very first view.(Rennie, 1826, p. 293)

Chinese boxes of colours

These boxes, which are beautifully painted and japanned, come from China. They contain each two dozen of papers, and in each paper are three smaller ones, viz. a small black paper for the eyebrows; a paper, of the same size, of a fine green colour, but which, when just arrived and fresh, makes a very fine red for the face; and lastly, a paper containing about half an ounce of white powder (prepared from real pearl) for giving an alabaster colour to some parts of the face and neck.(The art of beauty, 1825, pp. 192-193)

The use of pearl was not confined to face and body powders. Like many other precious materials, they were considered to have health benefits; for example, it was one of many exotic ingredients used in the eighteenth-century to make a cold nostrum referred to as Gascoign’s powder. Even today, many health benefits are ascribed to it. When taken orally, it is said to have ‘anti-ageing properties’ and when applied to the skin it is believed to be able to “tone and rejuvenate complexion, heal blemishes, minimize large pores and reduce redness”. However, although attempts have been made to find health benefits in conchiolin, none of these claims have been scientifically verified.

In the nineteenth-century, the use of imported powdered pearl was a luxury only afforded by a few. However, this did not stop the manufacturers of face powder invoking its name. Pearls are a symbol of whiteness, purity and costliness, which is perhaps why the entrance to Heaven was said to be through the Pearly Gates. By associating their powders with pearls, the manufacturers hinted that they had all these qualities, even when they were made of less expensive materials.

Blanc de Perle (Pearl white)

Is levigated talc mixed with a little almond oil and mucilage of gum tragacanth, and spread upon porcelain disks for convenient use.(Cristiani, 1877, p. 151)

There were however, only a few powders that could mimic the softness and whiteness of real pearl, the most important of these being the ‘bismuth-whites’.

Bismuth-whites

Known for their soft skin feel and adhesive properties, these were either bismuth oxychloride (referred to as base chloride or subchloride in the literature of the day) or bismuth subnitrate; bismuth oxychloride had a pearly sheen, while bismuth subnitrate had the advantage of being more astringent. When mixed together with other materials they went by names such as pearl powder, pearl white, bismuthine cream, blanc de perles and fard blanc de bismuth.

Blanc De Perles Sec (Dry Pearl White). Venetian chalk 20 Ib. Subnitrate of bismuth 42 oz. Zinc white 42 oz. Oil of lemon 1½ oz. (Askinson, 1923, p. 306)

Health warnings

In 1883, the Michigan State Pharmaceutical Association issued compiled a list of products on sale in America, many of which could be described as being pearl powders or liquid pearls.

Dr. Felix Gourand’s Oriental Cream or Magical Beautifier.—Mild chloride of mercury in suspension or deposit in water. The liquid contained a very little mercuric chloride (corrosive chloride), possibly resulting from decomposition of the mercurous chloride in the watery mixture.

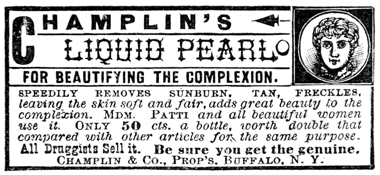

Champlain’s Liquid Pearl.—Oxychloride of bismuth (“pearl white”) and drop chalk, in highly perfumed water.

Stoddart’s Peerless Liquid.—Nearly the same as the article last above given. Oxychloride of bismuth, some preparation of chalk and water.

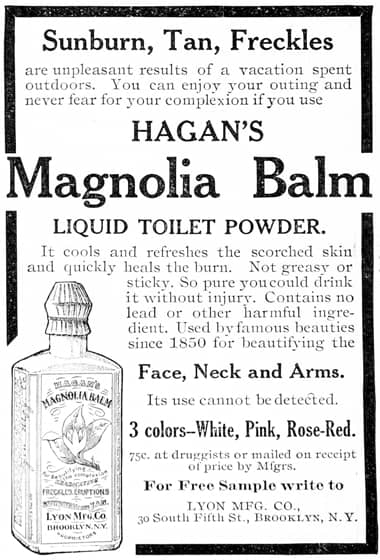

Hagan’s Magnolia Balm.—Oxide of zinc (zinc white) in perfumed water.

Laird’s Bloom of Youth, or Liquid Pearl.—Oxide of zinc (zinc white) and carbonate of calcium (as some grade of chalk) in perfumed water.

Excelsior of Beauty.—Lead white or flake white (basic carbonate of lead), drop chalk, chalk, carbonate of magnesia, and bay rum.

Youthful Tint.—Oxide of zinc (zinc white), essential waters. In another bottle, carmine and a prepared chalk.(Clark, 1883, p. 156)

Looking through this list, most are mixtures of white powders (only one of which contained lead) but some contained mercuric chloride and so would be better referred to as skin lighteners rather than whiteners. Given that lead pigment in powder was known to be harmful to health, some nineteenth-century writers also cautioned against the use of bismuth-whites.

The continued use of ‘bismuth-whites’ injures the skin, and ultimately produces paralysis of the minute vessels, rendering it yellow and leather-like – an effect which, unfortunately, those who employ it generally attempt to conceal by its freer and more frequent application.

(Cooley, 1896, p. 432)

Pearl-white is far more dangerous than rouge, as it is made of bismuth. Its use is most injurious to the skin, rendering it yellow and leather-like, and inducing paralysis if long continued.

(Modern etiquette, 1887, p. 167)

Some of this animosity may have been generated by the fact that these powders were sometimes associated with the practice of face enameling.

See also: Queen Alexandra and Face Enameling.

Fortunately, not all nineteenth-century writers agreed that the use of bismuth was a problem.

Some physicians have decried this metal in both these forms as injurious to the skin and unsafe to the general health. There is doubt about this opinion. We have given it for months, both internally and externally, without any ill results, and do not feel convinced that it is more objectionable on the score of health than French chalk.

(Brinton & Napheys, 1870, p. 208)

However, despite these more positive reports, the negative feelings associated with bismuth persisted. At the turn of the century, for example, Helena Rubinstein deemed it necessary to state that no lead or bismuth was used in her powders.

Valaze herbal face powder, contains no lead, chalk, or bismuth.

(Helena Rubinstein, 1906)

The bismuth-whites proved to be safe and went on to be widely used in the twentieth-century. Bismuth subnitrate – with its astringent properties – was used cosmetically in bleaching, freckle creams and hair dyes while bismuth oxychloride was incorporated into lipsticks, eyeshadows, and other cosmetics as a filler or synthetic pearl.

As well as doubts about their safety, bismuth-whites had another widely known drawback. Some forms tended to go grey when they came into contact with the sulphurous gas produced from coal fires or coal gas lighting.

It [bismuth] has, indeed, in common with all the metallic substances used for this purpose, one serious drawback. They are all changed by sulphurous gases into dark gray sulphurets, and as luck will have it, our coal fires and gas-pipes are constantly ready, whenever opportunity is allowed them to fill the apartment with just such gases. The consequence is that on not a few occasions, ladies, who at the outset of the evening displayed complexions which made their rivals ready to tear their hair with envy, have come to grief in the most unexpected manner, and been obliged to retire in confusion, with their faces of a dirty ash color, owing to some stupid servant mismanaging the furnace and allowing the gas to escape.

(Brinton & Napheys, 1870, pp. 208-209)

Other whites

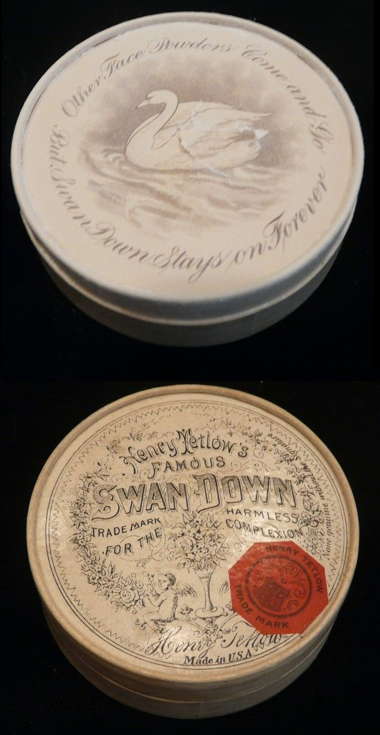

The use of bismuth compounds in face powders declined somewhat when zinc oxide was introduced. Henry Tetlow of Philadelphia was one of its early adherents, incorporating it into his face powders from 1866, including in the very successful Swan Down brand. Titanium dioxide was also used increasingly as a white pigment. It was a more brilliant white than zinc oxide and today is found in a wide variety of cosmetics.

Pearliness

As the twentieth century progress, cosmetic chemists became more interested in replicating the lustrous effects of pearls rather than their whiteness. Pearliness in the form of pearl essence – a product developed from fish scales – was first introduced into nail polish but other cosmetics soon followed. However, it was not until after the Second World War that ways were found to introduce the effect into powders.

See also: Pearl Essence

Updated: 4th February 2018

Sources

Askinson, G. W. (1923). Perfumes and cosmetics: Their preparation and manufacture (5th ed.). London: Crosby Lockwood and Son.

Brinton, D. G., & Napheys, G. H. (1870). Personal beauty: How to cultivate and preserve it in accordance with the laws of health. Springfield, Mass: W. J. Holland.

Cooley, A. J. (1866). The toilet and cosmetic arts in ancient and modern times with a review of the different theories of beauty and copious allied information social, hygienic, medical. New York: Burt Franklin.

Cristiani, R. S. (1877). Perfumery and kindred arts. Philadelphia: Henry Carey Baird and Co.

Modern etiquette in public and private. (1887). London: Frederick Warne and Co.

Rennie, J. (1826). A new supplement to the pharmocoepias. London: Baldwin Cradock and Joy.

Trying out pearl powder.

Freshwater pearls the source of modern pearl powder most of which originates in China.

An example of a contemporary product containing pearl powder.

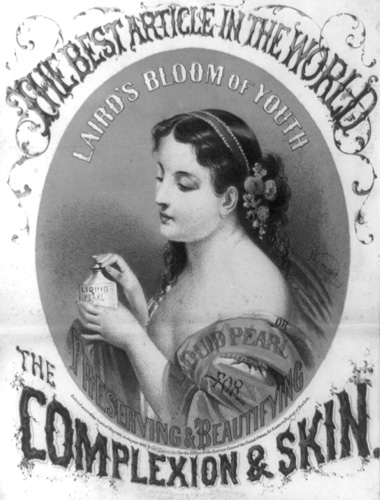

1863 Laird’s Bloom of Youth, or liquid pearl for preserving and beautifying the complexion and skin. The connection of pearls with whiteness, softness and purity is very evident. The product contained bismuth oxychloride (‘pearl white’) and calcium carbonate (chalk).

Tetlow’s Swan Down Face Powder.

1885 Champlin’s Liquid Pearl. It contained bismuth oxychloride (‘pearl white’) and calcium carbonate (chalk).

1910 Hagan’s Magnolia Balm. Made largely from zinc oxide (zinc white) this could perhaps be considered as a liquid pearl even though it was not described as such.

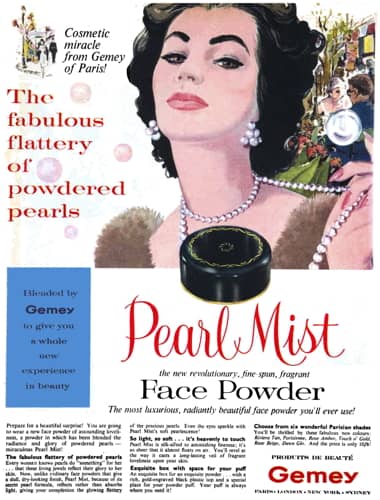

1959 Gemey Pearl Mist made with real pearl powder.