Hand Balms, Creams & Lotions

In Victorian times when a pale, flawless skin was considered desirable, a smooth, delicate, white hand was considered an important part of a woman’s charms.

A fine hand in male or female is always pleasing; and next to the charms of a beautiful face, a woman has an undoubted right to be proud of a fine delicately tapered hand, and a symmetrical and elegantly rounded arm.

(The toilette of health, beauty, and fashion, 1834, p. 137)

To protect their hands, women were advised to wear gloves when venturing outdoors and to apply soothing or softening preparations overnight. For clammy hands powders were suggested. Bleaches were recommended to lighten them but evening white could be smoothed on to make the hands look whiter when going out at night.

See also: Bleach Creams and Liquid Face Powders

Glycerine

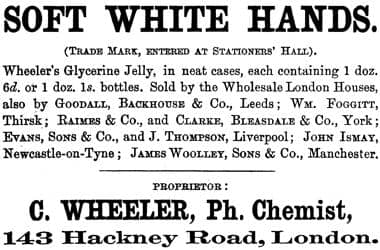

The soothing and softening power of cosmetics got a major boost with the introduction of glycerine in the late nineteenth century. It became an essential ingredient in many skin-care cosmetics including those used on the hands. Prior to this, greasy fats and oils were used to soften the hands overnight – applied under gloves to stop the grease from soiling the linen – with or without a whitening agent such as benzoin.

The use of “cosmetic gloves,” as they are called has long been known in some countries, and there are ladies who glove themselves as regularly on retiring to bed, as they do on the street. These gloves, when designed simply to soften and whiten the hands, are prepared by brushing inside a pair of stout kid or dog-skin gloves with the following mixture:—

Yelk [sic] of two fresh eggs,

Oil of sweet almonds, of each two tablespoonfuls;

Tincture of benzoin a dessertspoonful; Rose-water a tablespoonful.

Beat them well together, and keep in a closely corked bottle. The gloves should be freshly painted every night, and the same pair should not be used longer than two weeks.(Brinton & Napheys, 1870, pp. 154-155)

Glycerine was simple to use, did not have a greasy feel and could be worn under gloves during the day as well as smoothed on at night.

Since Baron Alibert’s time we have discovered something even better than the oil of Aix; it is glycerine. A bottle of pure glycerine—but chemically pure, remember, without any of those salts of lime or of lead which are found in much of the glycerine sold, and which will discolor and irritate the skin—should form an indispensable adjunct to every lady’s toilet set. A teaspoon of it in a pint of water will soften and protect the hands from the air. It should be rubbed in but not wiped off.

(Brinton & Napheys, 1870, p. 153)

Glycerine was commonly used to protect the skin from winter chapping. Its use was not restricted to the hands and most of the popular commercial skin-care cosmetics that contained it recommended its use on all parts of the body. Clark’s Glycola, for example, was suggested for the arms, face and hands.

Protect your skin using Clark’s Glycola—a little massaged well into the skin will keep your hands smooth, soft and youthful—used regularly before you go out at night, and in the morning, it will prevent ugly chapped hands and chilblains.

Glycola makes an excellent powder base and is economical in use. Before the dance or evening party massage a little on hands, arms and face, before applying powder.(Clark’s Glycola advertisement, 1933)

Glycola was not alone in this and until the 1930s many cosmetic lines used to soothe and soften the hands – such as Frostilla, Campana, Hinds, Jergens and Pacquins – were developed as general skin-care preparations. Consumers generally preferred liquid preparations (balms and lotions) to solids (creams) as these could more quickly and easily cover large areas of the body.

Balms

Many early preparations used on the hands were formulated as glycerine creams or jellies. Although some of these were called, or described as, lotions I will refer to all formulations of this type as balms to separate them from the liquid emulsions that became popular at a later date. A good example of this type of product was Campana Italian Balm, a Canadian cosmetic developed in the 1880s and first manufactured in the United States in the 1920s.

See also: Glycerine Creams and Jellies

Like their counterparts used to protect the face in cold weather most hand balms relied on glycerine as the anti-chapping agent. Commonly, they were made as a mixture of glycerine and rosewater with a gum (mucilage) added as a thickener. Early versions used natural gums – such as gelatine, karaya, tragacanth, quince seed, Irish moss, agar agar or gum arabic – with quince seed being the most favoured.

Jelly for the Hands (Monin) Gelatine 7 grams Glucose 30 grams Glycerine 180 grams Water 90 grams Oil of rose 5 drops (Durvelle, 1923, p. 257)

Later balms also used sodium alginate derived from seaweed, or synthetic gums such as carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) when it became available in the mid-twentieth century. Other additives sometimes included in these cosmetics included: boric acid for its antiseptic and soothing properties; alcohol to speed up the drying time; and citric acid as a skin lightener.

Hand Balm Lemon Lotion CMC Medium Viscosity 2.0% Glycerin 15.0% Citric Acid 4.0% Alcohol 8.0% Lemon Perfume 0.7% Water 70.3% (Keithler, 1956, p. 313)

Balms had a smooth, non-greasy feel when applied to the skin but they suffered from two major problems. First, even when alcohol was added, they took a relatively long time to rub into the skin and dry. Second, they often developed a slimy feel if the hands perspired or came into contact with water, even hours after the balm had been applied (Keithler, 1956).

Hand balms were still in some demand in the 1950s but by then their popularity had fallen well behind emulsified hand creams and lotions. However, they did not disappear altogether and glycerine balms are still being sold today, with Corn Huskers Lotion being a modern American example of the type.

Creams and lotions

In the 1920s, hand balms began to be supplanted by oil-in-water or water-in-oil emulsions. A good early example of a product of this type was Hinds’ Honey and Almond Cream, a liquid preparation advertised as both a hand and body lotion.

See also: A. S. Hinds

Commonly, formulations were modified vanishing (stearate) emulsions made up as a liquid cream (lotion). These were ‘greaseless’ and rubbed into the skin easily without rolling. Of course, women could simply use a vanishing cream on their hands and many did.

Before going out in winter days, rub a bit of vanishing cream into your hands. This will keep them soft. If you wear evening white on them when you go to parties, be sure to rub it in thoroughly and be equally sure to remove it before retiring as it is very drying.

(Hand yourself beauty, 1931, p. 104)

See also: Vanishing Creams

As with the balms, glycerine was still the primary emollient in the earlier preparations. Gums were often included to thicken them, help stabilise the emulsion and give the lotion a smooth feeling. Preservatives were also needed to prevent spoilage. An example formulation is given below:

Per Cent Stearic acid 3.00 Alcohol 5.00 Mineral oil 5.00 Triethanolamine 1.00 Glycerin 5.00 Water 76.85 Quince seed 3.50 Perfume 0.50 Preservative 0.15 (Chilson, 1934, p. 222)

Early hand lotions were dispensed from glass bottles so their consistency was an important consideration. If the lotion was too runny it would be difficult to use but if it was too stiff it would be hard to pour from the bottle. As well as adjusting the amount of gum in the mixture, the lotion’s consistency could be modified with substances such as ricinoleic acid: the more ricinoleic acid used the more fluid the lotion (deNavarre, 1941, p. 293).

Above: 1935 Assorted hand balms, lotions and liquid creams in glass bottles.

It was also possible to make a lotion along the lines of a traditional beeswax/borax cold cream. As these were water-in-oil emulsions they were not ‘greaseless’ but this would be less of a problem if they were spread on the hands at night under loose cotton gloves or applied to hands like a cleanser which was then rubbed in or largely removed with a cloth.

Per Cent Spermaceti 3.75 White beeswax 0.75 Glycerin 2.00 Pulverised neutral white soap 2.50 Borax 0.35 Almond oil 3.00 Quince seed 2.50 Alcohol 1.50 Water 83.00 Preservative 0.15 Perfume 0.50 (Chilson, 1934, p. 222)

Although not as popular as hand lotions, hand creams were also made. Like the lotions, most hand creams made in the 1920s were formulated along the lines of a ‘greaseless’ vanishing cream, with many including gums/mucilages their formulation.

Per Cent Stearic acid 10.50 Glyceryl mono stearate 2.50 Glycerin 4.50 Strong ammonia solution 2.50 Alcohol 3.50 Quince seed 2.25 Preservative 0.10 Water 73.65 Perfume 0.50 Procedure: [Soak the quince seed overnight in] two-thirds of the water; put the rest of the ingredients into a kettle and heat until a homogeneous solution is effected. Mix until the temperature drops to about 80° C. then stir in the quince seed mucilage and continue stirring until the temperature drops to 40° C. at which point add the perfume and preservative dissolved in the alcohol.

(Chilson, 1934, p. 105)

Hand creams were also made with added fats and oils or as water-in-oil emulsions. These could be used at night to soften the hands while sleeping or during the day on hands that were dry. Again, rather than buying a hand cream of this type, women could simply apply a cold cream or something similar.

Improvements in formulation

During the 1930s, American cosmetic chemists began to pay more attention to this class of cosmetics. This may have been due to an increase in consumer demand as housewives dispensed with their maids to save money as the Great Depression began to affect incomes (‘The Drug and Cosmetic Industry,’ 1932).

Last spring, when we were complaining about the status of hand preparations—and most explicitly hand lotions, something greater than the insight of the experts was pointing toward a change for the better. So it was no expert’s prediction that hand preparations would come through a renovation, and we take no credit, if any is ensuing.

Complaining about hand lotions we said, “gums aren’t healing at all; glycerine is overrated as an emollient; too little healing power in lotions when it is needed; why so much wax or cheap oil; and how about that free alkali . . . ”

The reaction that followed was so gratifying that we knew right then that work was being done on the problem.(deNavarre, 1935, p. 71)

As people became more budget conscious, preparations that had multiple uses also offered better value for money. Andrew Jergens, for example, also recommended its Jergens Lotion as powder base, a neck and arm softener, a sunburn and windburn protectant, an after-shave lotion in addition to it being a hand lotion and this may have boosted sales.

Also see the Jergens booklet: Your Skin and Its Care (c.1927)

The increased demand for hand cosmetics in the 1930s saw a number of cosmetic companies adding hand preparations to their skin-care lines during the decade. Most were creams which were easier to make than lotions although the consumer misconception that creams were more ‘powerful’ than lotions may also have been a determining factor. Examples included: Ogilvie Sisters Hand Cream, Cutex Hand Cream, and Marie Earle Hand Lotion (1932); Sofskin Crème, Pond’s Cream Lotion, and Helena Rubinstein Herbal Hand Balm (1935); Peggy Sage Gardenia Liquid Hand Cream, Elizabeth Arden Hand-O-Tonik, and Petalskin Hand Cream (1936); Rose Laird Shaperone Hand Cream, and Harriet Hubbard Ayer Hand Cream (1937); and Charles of the Ritz Velvet Glove Hand Lotion, and Revlon Hand Cream (1938). Even Campana followed the trend adding Campana Hand Cream to its existing Campana Balm in 1940.

Above: 1940 Campana Hand Cream.

The increased attention afforded to hand creams during the 1930s saw major improvements in formulations. Cosmetic chemists were helped by new research into the nature of emulsions and through the introduction of new raw materials such as lanolin absorption bases, glyceryl monostearate, triethanolamine compounds, acid emulsifiers and sulphonated fatty alcohols.

One important change was an overall reduction in the use of gums which, as mentioned earlier, could leave the hands feeling sticky when moist. The reduced reliance on gums now allowed many products to be advertised as ‘non-sticky’, an important consideration for many women.

Hand protectants

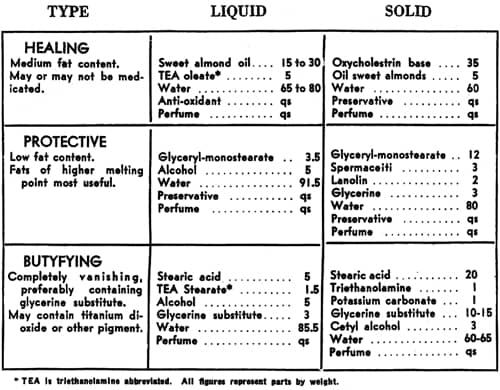

The healing, protecting and beautifying functions of pre-war hand preparations were nicely summarised by deNavarre.

Above: Formulation of liquid and solid hand cream preparations (deNavarre, 1935, p. 72).

The protective function of pre-war hand cosmetics was largely limited to reducing redness and chapping by applying a balm, cream or lotion after the household chores were finished. The development of protective hand preparations applied before the task was begun came about because of the Second World War.

Barrier creams and lotions

During the war there was an influx of women into heavy industry and other positions vacated by men inducted into the armed forces.

Above: Female factory worker in the 1940s.

Industrial work often resulted in the development of coarse hands or worse, industrial dermatitis. In many cases the problems were caused by scrubbing the hands with harsh cleansers after a shift was over rather than contact with chemicals during the working day. Men might put up with this but women doing similar work were generally not prepared to endure the consequences. Naturally women looked to hand preparations to help protect and/or restore their hands from the stresses of factory work but they often found that traditional hand creams and lotions did not function well enough. What was needed was a hand preparation that was applied before work as a protective barrier rather than smoothed on after work as a restorative.

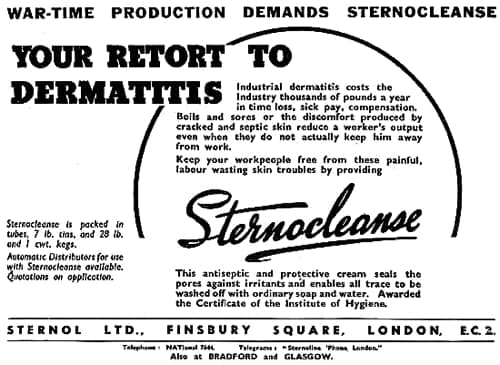

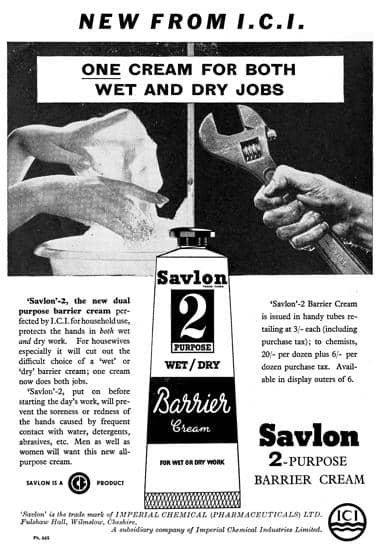

Britain entered the war over two years before the United States, and cosmetic chemists there became concerned about this problem well before their American counterparts. The Americans got more interested after 1942 and by 1945 a range of cosmetics that came to be known as ‘invisible gloves’ or barrier creams had been developed to help reduce the incidence of industrial dermatitis.

Above: 1940 Sternocleanse.

After the war some effort was made to convince women to use barrier creams in the home but, by and large, they failed to gain much traction in the domestic market.

See also: Barrier Creams & Lotions

Post-war

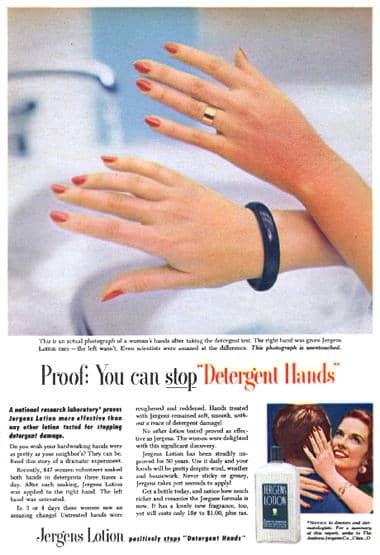

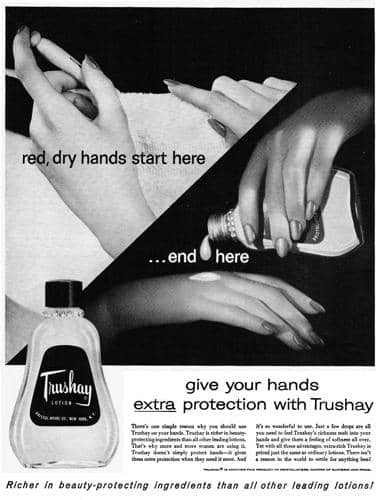

Women who came to appreciate the usefulness of a good hand cream or lotion during the war continued to use them in peacetime. Advertising of the period followed lines similar to those established before the war, accentuating the need to stop hands from becoming rough from housework and contact with ‘harsh detergents’. The idea of ‘harsh detergents’ was largely the invention of copywriters working for the large soap and detergent companies and there is little evidence that they were a significant cause of hand eczema or dermatitis.

As the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, hand preparations joined other skin-care cosmetics in highlighting their moisturising and anti-ageing qualities. Additives such as hormones, royal jelly and skin lighteners like hydroquinone were also used to try to give products a marketing edge and generate sales. However, as reported by Kalish, the readers of the American magazine ‘Good Housekeeping’ still considered effectiveness against roughness to be the most important quality for a hand cream or lotion (Kalish, 1959, p. 310).

Rough hands became less of a problem as new domestic appliances – such as washing machines and dishwashers – reduced the exposure of hands to chemical and physical insults during housework. However, as was the case before the war, many women used these cosmetics on other parts of their body. This may be the reason behind the continued popularity of hand lotions which were still outselling hand creams by at least three to one (deNavarre, 1975).

Decline

As the twentieth century continued to progress, cosmetic companies put more emphasis on general body-care cosmetics rather than products specifically for the hands. This remains the situation today. An examination of the cosmetic shelves at a local pharmacy, drug store, chemist or supermarket will reveal that body-care cosmetics now far outnumber those for hand-care, with products specifically labelled as hand lotions or creams relegated to a small section, often positioned on a lower shelf.

First Posted: 20th August 2017

Last Update: 2nd January 2022

Sources

Brinton, D. G., & Napheys, G. H. (1870). Personal beauty: How to cultivate and preserve it in accordance with the laws of health. Springfield, MA: W. J. Holland.

The chemist and druggist (1956). January 21, 66.

Chilson, F. (1934). Modern cosmetics. New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

deNavarre, M. G. (1935). Recent progress in materials and manufacture of hand preparations. The American Perfumer and Essential Oil Review, December, 71-72.

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston, MA: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.

deNavarre, M. G. (1975). Hand creams. In M. G. de Navarre (Ed.), The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 305-309). Orlando, FL: Continental Press.

Durvelle, J.-P. (1923). The preparation of perfumes and cosmetics. (E. J. Parry, Trans.). New York: D. Van Nostrand Company.

Hand yourself beauty. (1931). Screenland, February, 39 & 104.

Jannaway, S. P. (1936). Progress in hand creams. The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record, May, 208-210.

Jellinek, J. S. (1970). Formulation and function of cosmetics (G. L. Fenton, Trans.). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Kalish, J. (1942). Skin protective creams. Drug & Cosmetic Industry, 51(3), 279-280.

Kalish, J. (1959). Hand lotions and creams. Drug & Cosmetic Industry, 85(3), 310-311, 416.

Keithler, W. M. R. (1956). The formulation of cosmetics and cosmetic specialities. New York: Drug and Cosmetic Industry.

Lanzet, M. (1975). Cosmetic liquid emulsions. In M. G. de Navarre (Ed.), The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 397-419). Orlando, FL: Continental Press.

Lesser, M. A. (1940). Skin protectives. Drug & Cosmetic Industry, 46(3), 284-286, 323.

Poucher, W. A. (1959). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps with special reference to synthetics (6th ed., Vols. 1-3). London: Chapman & Hall Ltd.

Poucher, W. A. (1974). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (8th ed., Vols. 1-3). London: Chapman & Hall Ltd.

Ruggles, E. W. (1928). Working formula of Ruggles cream. Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology, 18(1), 136.

Strianse, S. J. (1957). Hand creams and lotions. In E. Sagarin, E. (Ed.). Cosmetics: Science and technology (pp.147-181). New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

The toilette of health, beauty, and fashion. (1832). London: Wittenoom and Cremer.

Van Alstyne, A. (1931). Hand yourself beauty. Screenland, February, 58-59, 104.

Wells, F. V., & Lubowe, I. I. (1964). Cosmetics and the skin. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

1875 Trade notice for Wheeler’s Glycerine Jelly.

1903 Trade advertisement for Campana Italian Balm, advertised as a specialist preparation for combating the drying effects of winter weather.

1906 Frostilla for face and hands.

1923 Sana-Balm.

1925 Thurston Hand Cream.

1925 Edna Wallace Hopper Youth Hand Lotion.

1927 Jergens Hand Lotion.

1931 Gymiel Jelly.

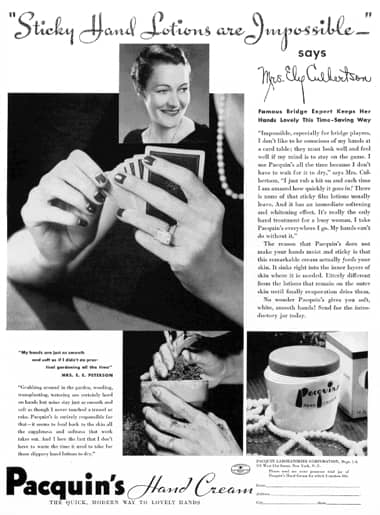

1932 Pacquins Hand Cream.

1932 Hinds Honey and Almond Cream.

1933 Larola lotion.

1934 Pacquins Hand Cream with suggestions that they have removed gums from the formulation to make their cream non-sticky.

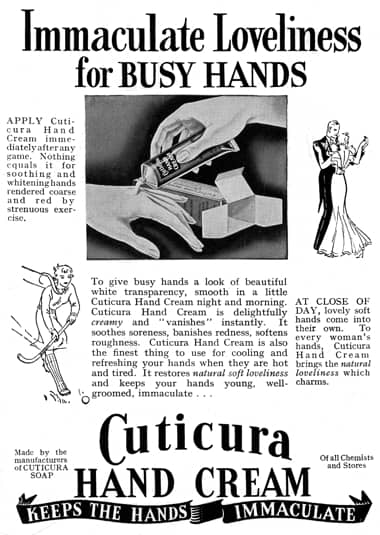

1939 Cuticura Hand Cream.

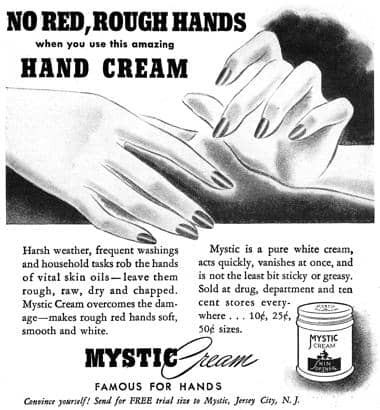

1939 Mystic Cream.

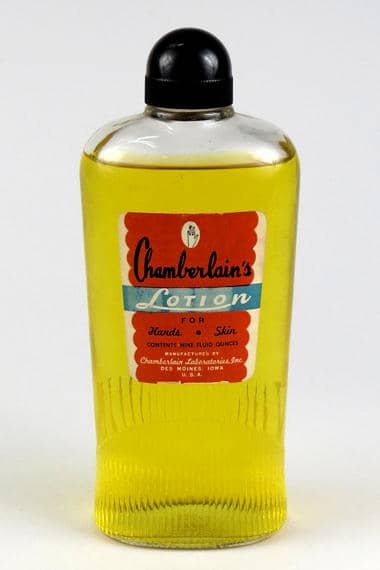

Chamberlain Lotion for Hands and Skin (Smithsonian). This is not a liquid-cream emulsion.

1942 Colgate Cashmere Bouquet Lotion.

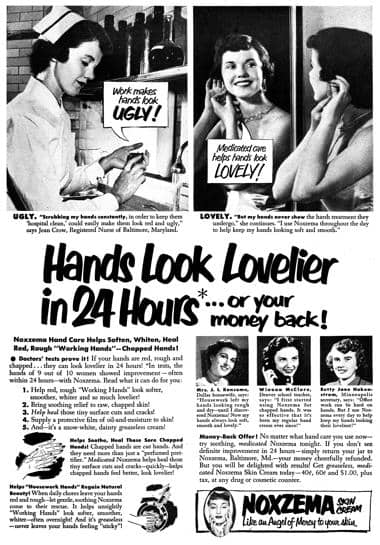

1951 Noxzema Skin Cream.

1953 Campana Italian Balm.

1955 Jergens Lotion.

1956 Savlon Barrier Cream.

1956 Trushay Lotion.

1956 Nulis (France).

1961 Pond’s Angel Skin Hand Lotion.

1965 Mitchum Esoterica Hand Cream with hydroquinone.