Barrier Creams & Lotions

Many industries use chemicals that are skin irritants which can lead to dermatitis with hands being a major point of contact. The consequences of exposure has been long standing issue with many occupations having names for specific problems; e.g., ‘baker’s itch’, ‘ink acne’, ‘zinc pox’ and ‘sugar itch’. It was also a widespread complaint. In 1938, 65% of all occupational disease in the United States, excluding accidents, were skin afflictions (Kalish, 1942, p. 279).

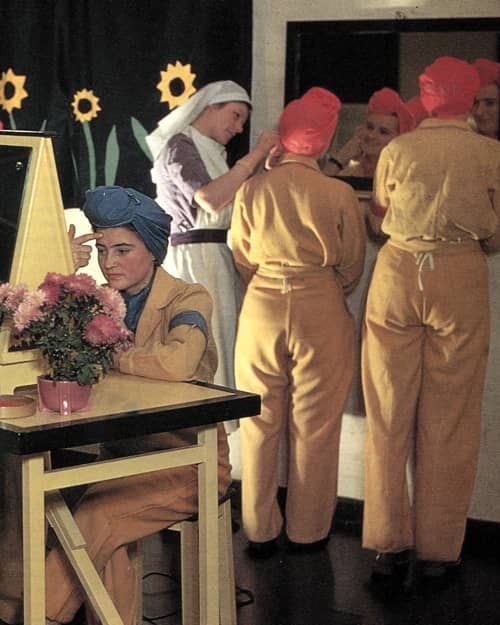

The expansion of the chemical industry during the Second World War and the introduction of new compounds focused attention on the issue. There were concerns that industrial dermatitis would reduce productivity and harm the war effort but it seems likely that the main impetus for change came from the influx of woman into industries to do work previously done by men.

We very strongly suspect that the recent greatly increased demand for products to protect the hands and permit them to be more thoroughly cleaned at the end of the day stems from the influx of women into war work. The rough and tough male mechanical operator would not do anything so effeminate as rubbing a cream on his hands and face before starting work. But he has been changing his mind recently, since he has seen his feminine co-worker, by the use of creams, continue her job untroubled by the imbedded grime and occupational dermatitis that have been bothering him.

(Kalish, 1942, p. 279)

One way to protect the hands was to wear gloves but this was not always feasible. Gloves could be uncomfortable, they could hinder delicate work and could cause skin irritation through excessive perspiration when worn for long periods.

Covering the hands with some sort of protective cream or lotion was another possible solution. This was an old idea. For centuries labourers in many industries had protected their hands by rubbing in clean grease before starting work. Some commercial products had also been produced. For example, Mir-A-Kal paste, sold by the Mooers-Wright Company of New York from the 1920s, claimed to protect the hands from dirt and grease when working automobiles.

Britain had been at war for over two years before the United States declared war, so chemists there became concerned about this topic well before their American counterparts.

Above: Women working in the Royal Ordnance factory during the Second World War applying make-up to help protect their skin from absorbing toxic chemicals such as 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT).

However, by the end of the war there were a number of protective hand preparations available on both sides of the Atlantic. These were generally referred to as ‘barrier creams’ in Britain and the Commonwealth but not in the United States. In America, most preparations of this type were sold under their trade name due to the misbranding conditions of the 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act (FDCA) which put cosmetic manufacturers using the words ‘protective’ or ‘barrier’ at risk of prosecution.

[W]ithin the past year, a number of so-called “protective creams” have appeared on the market. These products are not protective because the word implies too much. For example, such a cream will not protect the hands from being blown off as the result of an explosion, or from being cut by flying missiles. Yet such protection is implied by the title of the product. The creams therefore are mislabeled, and such mislabeling may bring these products within the purview of the Federal Trade Commission or the Food & Drug Administration, or both. They could more properly be called “industrial creams” or by a trade name such as “Sentry Hand and Face Cream” or “Guard” or “Patrol brand Industrial Cream.”

(deNavarre, 1942, p. 35)

Interest in industrial dermatitis did not cease with the end of the war. It continued to attract interest from governments and industry and it remains an issue to this day.

Above: 1950 Industrial Dermatitis by the U.K. Ministry of Labour.

Industrial cleansers

A major source of skin irritation came from the harsh cleansers, solvents and abrasives many workers used to remove grease, grime and other stains from their hands at the end of their shift.

Above: Deep fissures created by ever harsher cleansing methods used to clean dirt from fissures created by harsh cleansers. Men might be prepared to have their hands feeling rough after cleaning but this was not something most women would live with.

Therefore, part of the solution to industrial or occupational dermatitis included the formulation of skin cleansers tailored to the chemicals used in specific industries.

Formulation

Until the introduction of perfluoropolyethers in the 1980s, a universal barrier cream or lotion was not a consideration. The wide range of soils, solvents and other irritants used in industry – including petroleum oils and greases, explosives, fumes from soldering or welding, alkalis from cement and concrete, solvents, dyes, rubber, paints, varnishes and synthetic resins – meant that what would work as a protective in one situation could fail in another.

Despite the large range of chemical irritants, most barrier creams fell into one of two types: those that defended against water-soluble chemicals including detergents, and those that protected the hands from oil-soluble irritants, solvents and oils. Additional ingredients could be added to either of these to neutralise specific chemicals if appropriate compounds were available. It is not my intention to cover these in great detail as I am primarily interested in the application of barrier creams to households. However, below are listed four formulas recommended by the 1955 British Pharmaceutical Codex Sub-Committee which they thought were likely to afford some protection against the more common hazards:

Dust Barrier Casein (Rennet, Finely Powdered) 3 Sodium Alginate 2 Glycerin 6 Stearic Acid 10 Triethanolamine 1.55 Chlorocresol 0.5 Phenol 0.5 Distilled Water to 100

Water Barrier Hard Paraffin 25 Soft Paraffin 1.75 Liquid Paraffin 3.5 Cetostearyl Alcohol 5 Triethanolamine 0.7 Stearic Acid 1.8 Chlorocresol 0.2 Distilled Water to 100

Oil and Solvent Barrier Kaolin (Sterilized) 20 Bentonite 3 Hard Soap (Powdered) 12 Glycerin 6 Stearic Acid 2 Sodium Chloride 1 Chlorocresol 0.2 Phenol 0.5 Distilled Water to 100

Skin Conditioning Cream Monostearin, Self-emulsifying 10 Glycerin 6 Triethanolamine Ricinoleate 1 Wool Alcohols 6 Chlorocresol 0.2 Oleyl Alcohol 3 Distilled Water to 100 (‘British pharmaceutical codex—Barrier substances,’ 1955, p. 121)

None of these formulas contain silicones which came to be the most widely used water-repellant compounds.

Domestic market

As the Second World War came to an end, many cosmetic companies looked into household uses for barrier creams and a number of products were released onto the domestic market after the war.

Above: 1950 A scientist in an Innoxa laboratory demonstrating the effectiveness of a barrier cream.

Most of the household barrier creams and lotions were modified stearate or vanishing creams containing water-repellant silicones such as polydimethylsiloxane. A sample formula for a silicone lotion is given below:

(parts by weight) A Polydimethylsiloxane 350 ctks [centistokes] 5.0 Glyceryl monostearate (pure) 6.0 Mineral oil 65/75 2.0 Lanolin 1.0 Stearic acid XXX 4.7 B Glycerin 2.0 Triethanolamine 0.9 Water, q.s. 100.0 Perfume and preservative, q.s. Procedure: Heat A to 85°C. Heat B and preservatives to 85°C. Add A to B while mixing; perfume at 40°C. Mix well and package.

(deNavarre 1975, p. 317)

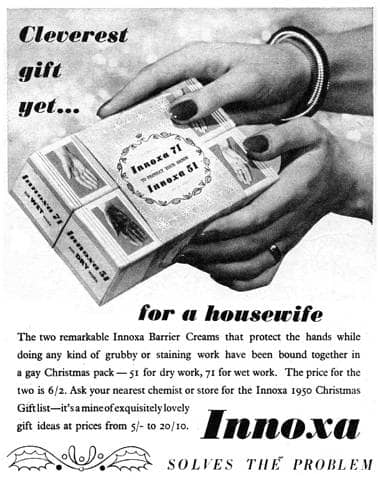

Barrier creams and lotions, or their American equivalents, were generally advertised as protecting the hands against the stresses of household chores and contact with soaps and detergents in particular. Some cosmetic companies, like Innoxa, marketed separate products for use in wet or dry situations but others developed products that were effective in both wet and dry situations.

As a group, hand cosmetics advertised as barriers were not successful in the domestic market. In 1956, ‘The Chemist and Druggist’ noted that although three out of four British women used a hand cream or lotion, only one out of ten had ever used a barrier cream.

The reason for the failure is unclear. It is possible that some were poorly formulated, did not contain the right silicone or enough of it to be effective or both (deNavarre, 1975, p. 312) but other factors may have been in play. Advertisers of the period may have found that women responded more positively to claims that hand creams were soothing, anti-ageing and moisturising and many women simply wore gloves when washing the dishes or doing housework.

Where products advertised as a barrier did find a ready market was in those designed to help prevent diaper rash.

Above: Revlon Baby Silicare Lotion. It contained glyoxyl diureide, polydimethylsiloxane and hexachlorophene (Smithsonian). The range also included Medicated Baby Silicare Powder.

However, even here the domestic need for barrier products may be in decline. The increasing use of disposable nappies – which draw fluid away from the skin – has made the regular use of a diaper cream less necessary.

See also: Hand Balms, Creams & Lotions

First Posted: 7th February 2017

Last Update: 25th May 2021

Sources

Alberman, K. B. (1964). Barrier creams and cleansers. The Chemist and Druggist. August 29, 200-201.

British pharmaceutical codex—Barrier substances. (1955). Occupational Medicine, 4(4), 121.

Cook, M. K. (1959). Barrier creams. Drug & Cosmetic Industry, 84(1), 32-33, 110-112.

deNavarre, M. G. (1942). Preventing industrial dermatitis. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review, December, 35-36.

deNavarre, M. G. (1975). Protective and barrier creams. In M. G. de Navarre (Ed.), The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 311-322). Orlando, FL: Continental Press.

Hopkins, S. J. (1947). Industrial dermatitis and the formulation of barrier creams. Manufacturing Chemist and Manufacturing Perfumer, 18(9), 389-393.

Kalish, J. (1942). Skin protective creams. Drug & Cosmetic Industry, 51(3), 279-280.

Kalish, J. (1959). Hand lotions and creams. Drug & Cosmetic Industry, 85(3), 310-311, 416.

Lesser, M. A. (1940). Skin protectives. Drug & Cosmetic Industry, 46(3), 284-286, 323.

Redgrove, H. S. (1941). Skin protective creams. The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record, January, 16-17.

Schwartz, L. (1943). How to protect the glamorous hands of industry. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review, August, 43-46.

Wells, F. V., & Lubowe, I. I. (1964). Cosmetics and the skin. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

1940s U.S. Employment Service’s poster encouraging women to take up places in industry.

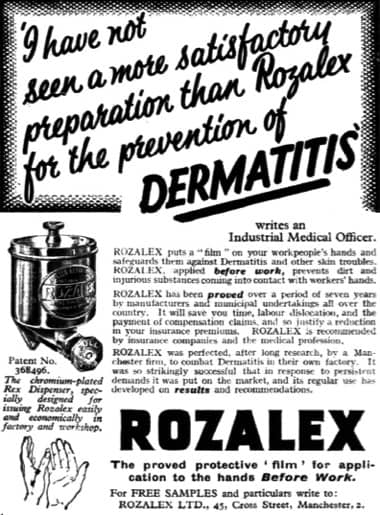

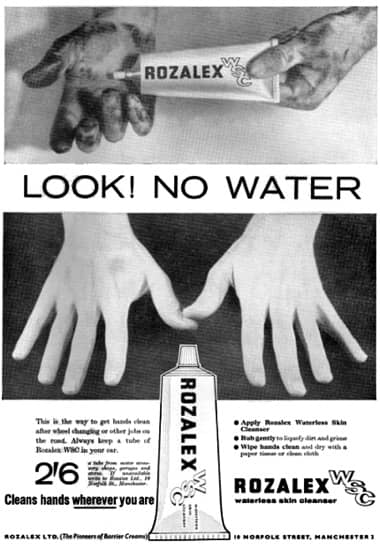

1937 Rozalex Barrier Cream.

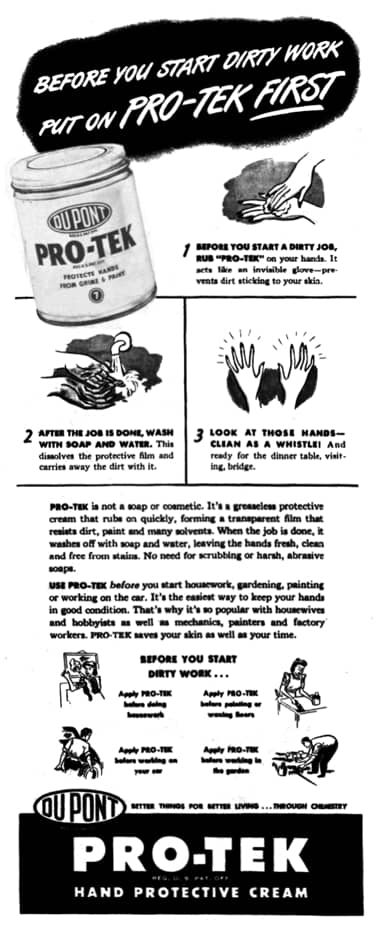

1945 DuPont Pro-Tek Hand Protective Cream.

1950 Innoxa Barrier Creams. Innoxa 51 for dry work and Innoxa 71 for wet work.

1952 Gauntlet Barrier Cream for wet and dry use.

1953 Lenthéric On Hand.

1953 Faulding “Barrier” Cream.

1957 Imperial Chemical Industries Savlon 2 - Purpose Barrier Cream.

1960 Rozalex Skin Cleanser. Specialist cleansers helped with controlling industrial dermatitis.

1961 Revlon Medicated Silicare. Developed in 1955 by the Pharmacal division of Revlon it contained polydimethylsiloxane and hexachlorophene.

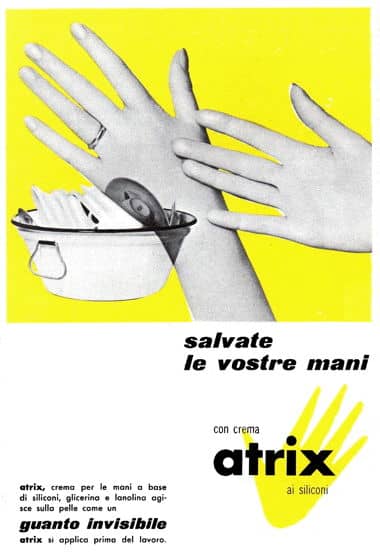

1961 Atrix guanto invisibile (invisible glove) ai siliconi (with silicones).