Make-up, Personality and Types

Although a pleasing external appearance was admired, women in the nineteenth century were often told that ‘true beauty’ came from within.

The first lesson to be learned, therefore, by the girl or woman who seeks the development of her own beauty, is that enduring beauty comes from within, that lovely thoughts create curves of loveliness in face and form, and that the more susceptible she becomes to their elevating influence, the greater is their vitality, and the more effective the work of the refining chisel.

(Fletcher, 1899, p. 14)

As more women entered the workforce in the twentieth century they soon realised – or were told by beauty writers, fashion columnists and advertisers – that appearance was at least as, if not more important than good character for success at work and in their personal and social life.

Now the first thing of which we are aware when we meet a woman is her looks. When we say Mrs. So and So is beautiful, we are referring always to her appearance. Beauty of character, wit, intelligence, these are recognized later. But, human nature being what it is, it is our appearance by which we first are judged. Appearance may be called by other names, we may speak of charm, of personality, of individuality, but each of these terms is summed up in the one word, beauty.

Yet beauty alone not sufficient to warrant our admiration. Beauty must have its proper setting. You have met one woman whose features perhaps are not regular, whose proportions are not equal to those of the Venus de Milo, yet because she has understood the art of enhancing her appearance by the right clothes, by a hair arrangement that is smartly becoming, by a hat that is perfect for her, she will call forth your admiration where another woman of greater natural beauty but less knowledge of dressing will not.

In such a case, one speaks of the first woman as having that intangible quality we call charm or personality. What then constitutes charm or personality? To my way of thinking, charm consists in the possession of an intelligence, which, when applied to the dressing and care of one’s self results in making the most of the features Nature has given one.(Stote, 1926, pp. 4-5)

Appearance became more critical for women during the depression years of the 1930s when competition for employment increased, or that is what women were told.

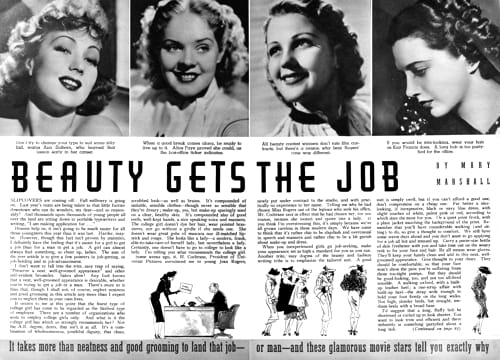

Above: 1937 Beauty Gets the Job (Marshall, 1937, pp. 44-45).

In the United States individuality was also stressed. Women there were advised to select clothing, hair and make-up that reflected their personality in addition to making them fashionably attractive; in other words, to develop a personal style (Berry, 2000). This was a new idea at the time and one particularly stressed by fashion experts.

One way for a fashion colomnist to advise women on developing a personal style was to describe a range of ‘types’ women could select from. These types included physical features such as body shape and colouring but often included personality traits or temperaments. For example, in her 1938 book, ‘Designing Women’, Margaretta Byers describes six fashion types – Coquette, Sophisticate, Romantic, Patrician, Gamine and Exotic – and suggested suitable clothing for each.

The Coquette

Examples: Billie Burke, Elizabeth Arden, Lily Pons.

Physical characteristics: petite figure, retroussé features, curled coiffures.

The Sophisticate

Examples: The Duchess of Windsor, Ina Claire, Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt.

Physical characteristics: trim, slender figure, irregular but striking features, sleek coiffure.

The Romantic

Examples: Princess Matchabelli, Greta Garbo, Princess Paley.

Physical characteristics: pre-Raphaelite figure, chiseled features, wistful eyes, artistic unstudied coiffure.

The Patrician

Examples: Mrs. Harrison Williams, The Duchess of Kent, Lynn Fontanne.

Physical characteristics: slender curves, exquisite skin and hair, soft coiffure.

The Gamine

Examples: Katharine Hepburn, Elsa Schiaparelli, Beatrice Lillie.

Physical characteristics: boyish almost gauche figure, impudent features, rebellious hair.

The Exotic

Examples: Marlene Dietrich, Tallulah Bankhead, Helena Rubinstein.

Physical characteristics: svelte figure, pale features, large eyes, extreme coiffures.(Modified from Byers, 1938, pp. 117-133)

If a woman identified with a particular type she could then follow the fashion advice given for it as the basis for a personal style. Although useful, this approach contained an inherent contradiction: the idea of expressing individuality by conforming to a type.

Make-up and types

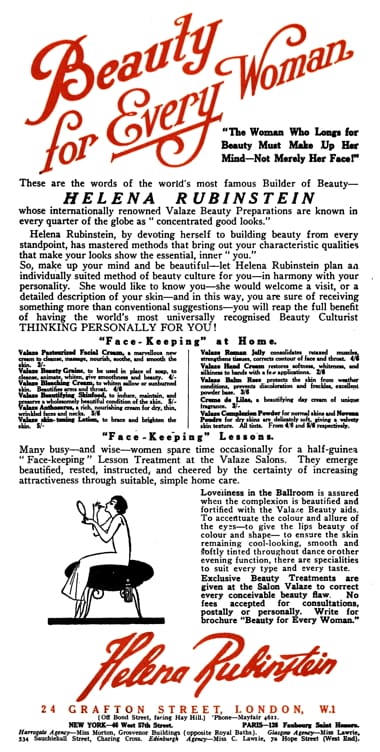

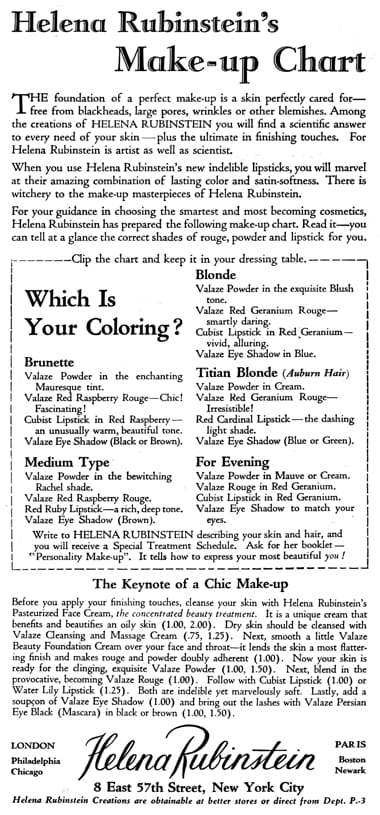

Although advice columnists often concentrated on clothing when discussing a personal style, hair and make-up were also considered. Beauty Culturists had long been preaching the idea that women should make the most of their beauty and that any woman could look attractive with the right treatments. Some, such as Helena Rubinstein [1871-1965], were keenly aware of the benefits to their business of suggesting that their beauty treatments harmonised with, and brought out, a client’s personality.

Helena Rubinstein, by devoting herself to building beauty from every standpoint, has mastered methods that bring out your characteristic qualities that make your looks show the essential, inner “you.”

So, make up you mind and be beautiful—let Helena Rubinstein plan an individually suited method of beauty culture for you—in harmony with your personality.(Helena Rubinstein advertisement, 1924)

Beauty Culturists were also familiar with the use of types, at least on the small scale, having long referred to skin types – viz., normal, dry or oily – to help women select a suitable skin-care product. As the use of make-up became more widespread, types were also used to describe how make-up could enhance specific facial features such as the eyes, lips or the shape of the face. For example, women could be shown a range lip shapes created with lipstick and then select the type they thought best suited them.

Above: 1921 Lip shapes or types (Photoplay magazine).

In the 1920s and 1930s, cosmetic companies also used types to sell make-up. Although most only had a limited number of shade in their ranges the possible colour combinations of powder, rouge, lipstick and eye make-up were still daunting for the inexperienced. In addition, although many companies used the same shade names – e.g., Natural, Rachel or White – this was no guarantee that the colours would be the same in different brands. This meant that each brand had to educate their clients/customers on how to select and coordinate appropriate shades of make-up to best effect. This was where types proved useful.

Make-up and colour

The types developed by cosmetic companies to colour coordinate their cosmetics were usually based on hair, eye and skin colour, as for example this set described by Helena Rubinstein:

Because each separate type of beauty demands a different coloured rouge and lipstick, a different shade of powder and eye pencil, I am giving below a beauty chart. Pick out which type you are and I can then advise you the proper shades you should use to enhance your natural loveliness:

Nordic Blonde: Fair hair, blue eyes, fair skin.

Anglo-Blonde: Ash-brown hair, brown eyes, creamy skin.

Celtic Blonde: Medium-brown hair, hazel or gray eyes, ivory skin.

Titian Blonde: Auburn hair, brown eyes, white skin.

Anglo-Brunette: Brown hair, brown eyes, fair skin.

Mayflower-Brunette: Brown hair, hazel, blue or gray eyes, ivory skin.

Latin-Brunette: Black hair, dark eyes, olive skin.(Reilly, 1929, p. 103)

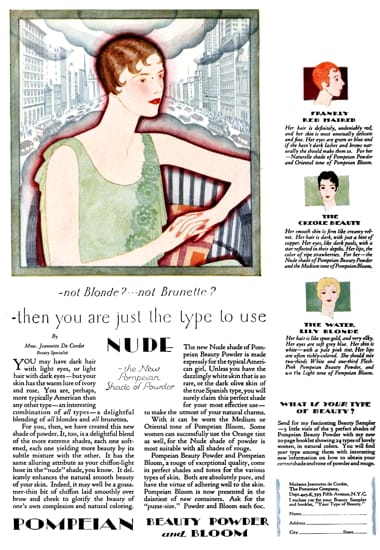

One issue with this approach was that many women did not recognise themselves amongst the types listed. Some cosmetic companies used a larger range of types but whole groups of women – such as those with very dark skins – were still left out. In 1927, for example, the Pompeian Manufacturing Company created a set of twenty-four beauty types – including Dresden-China Blonde, Watteau Blonde, Wild-Rose Girl, Frankly Red-Haired, Spanish Brunette, Cleopatra Brunette, Auburn Beauty, Creole Beauty and Coquette – to explain how its Pompeian Beauty Powder and Pompeian Bloom (rouge) were to be selected and combined.

Auburn Beauty

Her hair is reddish brown. She has a fine warmth of tone to her skin. Her eyes exactly match her hair. They look almost like sherry they are so limpid, and so nearly its color. (For her—2 parts Nude to 1 part Flesh-Pink with Orange or Oriental tone of Bloom.)

Creole Beauty

Her beauty is a direct inheritance from her French and Spanish forebears. There is in her face all the vivacity of the French, all the romance of the Spanish. Her skin is like creamy velvet. Her hair is dark, sometimes with just a hint of copper. Her eyes are like twin dark pools, with a star reflected in their depths. (For her—the nude shade of Pompeian Beauty Powder, and Medium tone of Bloom.)(Pompeian advertisement, 1928)

See also: Pompeian Manufacturing Company

Make-up and personality

Although concentrating primarily on colour, cosmetic companies frequently included personality traits or temperaments when constructing their beauty types as this made using their make-up seem more exciting. Some of the categories described by Pompeian show evidence of this:

Dresden-China Blonde

Quaint and flirty, young and alluring. Her skin is white with the faintest pink shining through. Her eyes are blue and wide and round. (For her—White Pompeian Beauty Powder with Light tone of Bloom.)

(Pompeian advertisement, 1928)

In 1929, the Armand Company went further and tried to ‘scientise’ the link between personality and make-up. Armand engaged a psychologist to work with a beauty expert and came up with a scheme to give the impression that Armand make-up was customised to match a woman’s personality. Armand then developed a booklet – aptly titled ‘Find Yourself’ – which supposedly allowed women to match their make-up with their personality.

This booklet is based on the principle that you must study your own type in order to learn the proper use of cosmetics. This is accomplished by the simple process of asking yourself a few questions. Truthful answers will enable you to work out your own Number, under which you will find revealed, as though the booklet had actually seen and heard you, interesting facts about your appearance and psychology, as well as a specific discussion of your individual problems. The knowledge gained from this discussion will start you on the road to Beauty. And that way lies Happiness.

(Armand Company, 1929, p. 3)

Using a short questionnaire, women could determine their key number which would lead them to an insight into their personality along with the shades of Armand lipstick, powder and rouge that best suited them.

Key No. 2

Your answers indicate that you are alert and up-to-date, that you are already giving your skin the attention it deserves and realize that keeping a youthful appearance is part of the capable handling of life. Your skin would be best suited by the Starlight or Creme tint of powder, or possible the Natural. Do not attempt the sunburn style. Either Zanzibar or Afterglow rouge and lipstick should suit you. If it amuses you to change your appearance from day to day, keep both on hand. Silver and gold are becoming to one of your colouring and when you look your best you suggest the ethereal freshness of a clear and dewy dawn. Yours is the type that catches and holds the masculine eye.(Armand Company, 1929, p. 9)

Also see the company booklet: Find Yourself

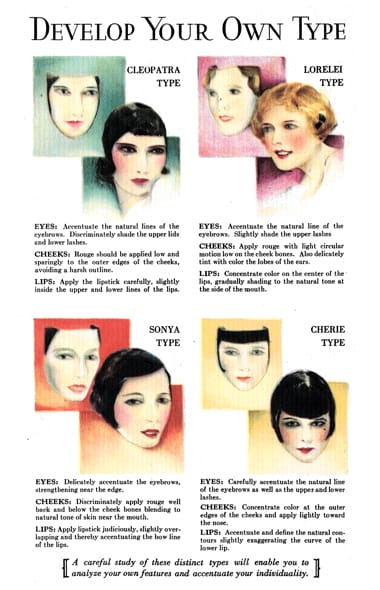

Once they knew what make-up shades they should use, these were applied according to one of eight beauty types created by Armand – Cleopatra, Lorelei, Sonya, Cherie, Sheba, Godiva, Mona Lisa or Coleen – as illustrated in the centre of the booklet. Although a good deal of effort went into this booklet it did not appear to get many women to switch to Armand make-up and the idea was not subsequently followed-up.

See also: Armand Company

Make-up, types and movie stars

The development of the motion picture industry and the rise of Hollywood through the 1920s and 1930s had a growing influence on fashion, hair and make-up. Actresses made ideal subjects for make-up types for a number of reasons. First, most of the leading actresses – and actors for that matter – contracted by the various Hollywood studios suffered from a degree of type-casting which meant that their physical appearance was associated with a particular personality or temperament type and they played the same character type through most of their movies. Second, actresses were increasingly subjected to the dictates of studio make-up artists who made them up according to a Hollywood style. This meant they maintained a fairly consistent style of make-up through all of their movies. There were some exceptions to this; e.g., a player was made up to look aged or had their make-up altered for an historical picture. Together, these two factors meant that identification with a movie star frequently included perceived similarities with the look and personality of the star on the screen.

Somewhere in Hollywood you have a double. If she doesn’t resemble you closely enough to be taken for a twin sister, you and she at least have enough facial features in common to make your friends think of you when they see her picture cast on the screen. The chances are that this hollywood double of yours not only resembles you in appearance but that she and you are something alike in your tastes and disposition, since superficial appearance is usually a reflection of innate characteristic.

(“Which type are you?,” 1935, p. 30)

Above: 1935 Which type are you?

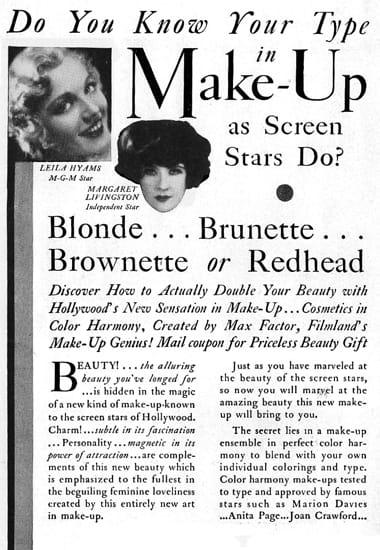

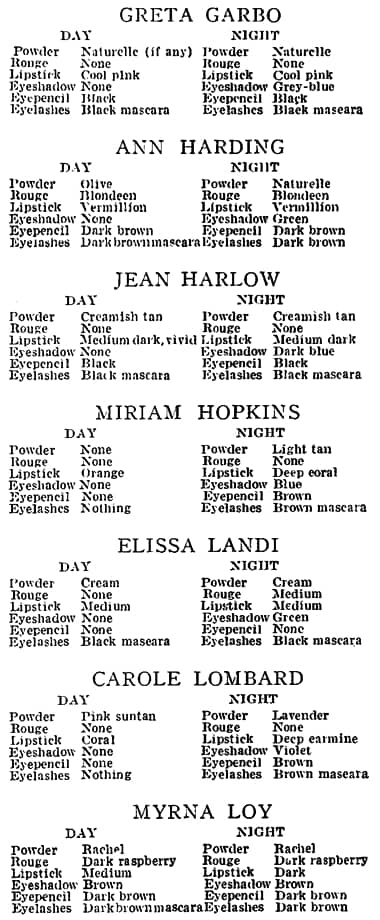

No one combined types and Hollywood movie stars to sell make-up more effectively than Max Factor. He recommended selecting and coordinating shades of make-up by beauty types based on hair colour: Blonde, Brunette, Redhead and Brownette, the last being a personal invention. Each of the four beauty types could select from a number of different shades of lipstick, face powder, eyeshadow and other forms of make-up but rather than complicating matters by introducing a wider range of types, Max Factor used individual actresses to demonstrate possible variations.

Above: 1931 Max Factor Color Harmony Make-Ups for Redheads.

By doing this Max Factor kept his range of beauty types relatively simple and included a personality factor all tied to the glamour of Hollywood. Women who identified with a particular movie star – by look, temperament or some other reason – could follow the guides Max Factor set out for that film star. He had a huge stock of actresses under contract, so these examples could be updated as the popularity of particular actresses waxed and waned.

See also: Max Factor and the Max Factor company booklet: The New Art of Society Make-up (1931)

Types and transformation

As the use of make-up increased, its transformative power became more recognised. The motion picture industry played a role in this through the widely publicised makeovers that actresses undertook when starting their screen careers. Like the movie stars, women were increasingly encouraged to change their clothing, hair and make-up, to make themselves over and become the type of person they wished to be.

Cast yourself in a certain role and dress the part. This is the subtlest aspect of taste, the greatest aid in achieving distinction and incidentally the most fun.

(Byers, 1938, p. 116)

Cosmetic companies responded to this idea in a couple of ways. Some embraced the idea of the makeover while others focused more on the colour changes in the fashion cycle.

A good example of a company aligning itself with the fashion cycle was Elizabeth Arden. In the 1930s, Arden moved away from recommending make-up shades according to complexion, hair and eye colour. Instead of providing her clients with make-up charts based on types, Arden’s charts of the time cross-referenced shades of make-up – powder, eyeshadow, lipstick, mascara and the like – with current fashion colours. This supposedly enabled women to change their natural colouring sufficiently to allow them to wear the latest fashion shades; i.e., to circumvent the confines of their type. Arden later declared that “any woman can wear any colour” (Elizabeth Arden, 1936).

See also: Elizabeth Arden (1930-1945)

Some cosmetic companies also recognised the inherent contradiction in expressing individuality by conforming to a particular type and campaigned against it. For example, the Lady Esther Company, one of the leading sellers of face powder in the 1930s, used an aversion to types to help sell its face powder.

The reason you haven’t found this right shade long ago is probably because you’ve been choosing according to your “type”—a blonde should wear this, a brunette that. This is all wrong! You aren’t a type. You’re yourself. And how lovely that self can be—how vivid, alive and bright—you’ll never know till you try on all five of my basic shades in Lady Esther Face Powder.

(Lady Esther advertisement, 1937)

Going further, Lady Esther suggested that a new powder shade should not be used to reflect a type but rather to create “a New Personality—a New Glamour—a New Charm!” (Lady Esther advertisement, 1937).

Post-war types

Cosmetic companies who used types to sell make-up between the two World Wars generally based these on traditional European skin, eye and hair tones. After 1950, as Western cosmetic companies embraced customers that were more ethnically and culturally diverse, classifying women by type became more complex and the practice declined even further. This does not mean that types disappeared from make-up advertising altogether and the idea resurfaces every now and again.

Updated: 18th February 2019

Sources

Armand Company. (1929). Find yourself [Booklet]. Author.

Berry, S. (2000). Screen style: Fashion and femininity in 1930s Hollywood. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Byers, M. (1938). Designing women. The art, technique and cost of being beautiful. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Fletcher, E. A. (1899). The woman beautiful. A practical treatment on the development and preservation of woman’s health and beauty, and the principles of taste in dress. New York: W. M. Young & Co.

Frederick, C. (1929). Selling Mrs. consumer. New York: The Business Bourse.

Marshall, M. (1937). Beauty gets the job. Modern Screen, October, 44-45, 91-93.

Max Factor. (1928). The new art of society make-up. U.S.A.: Author.

Peiss, K. (1998). Hope in a jar: The making of America’s beauty culture. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Reilly, R. (1929). Bring beauty to every girl. Screenland, XVII(6), 70-71, 102-103.

Stote, D. (1926). Making the most of your looks. New York: Brentano’s Inc.

Which type are you? (1935). New Movie, 11(1), January, 30-31.

1921 Dorin of Paris. The advertisement asks the reader to “Intensify your type of beauty” and “Study your own coloring”.

1924 Helena Rubinstein. Beauty for Every Woman.

1926 What Style of Bob Suits Your Type? (Picture-play).

1927 Pompeian beauty types.

1929 Max Factor. Do You Know Your Type in Make-up as Screen Stars Do?

1929 Helena Rubinstein Personality Make-up Chart which explains how to “express your most beautiful you”. As beauty experts like Helena Rubinstein pushed the idea that a good skin-care routine and appropriate make-up could make any woman beautiful, looking one’s best became almost a duty.

1929 Armand. Develop Your Own Type.

1929 Max Factor. How to Emphasize Personality with Make-Up.

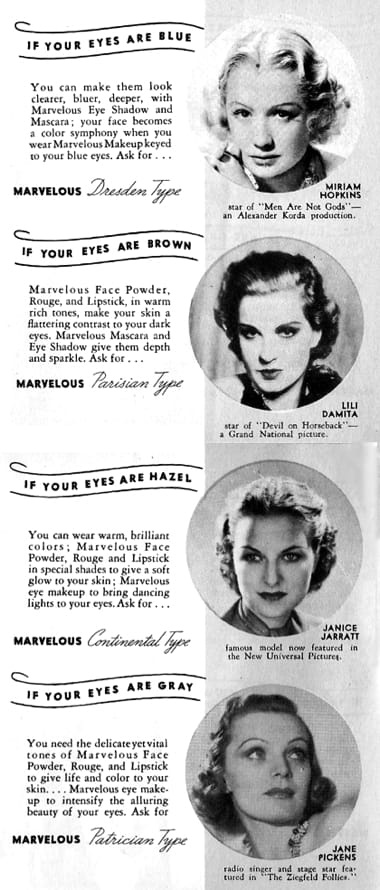

1931 Richard Hudnut beauty types based on eye colour.

1933 Eye Make-Up Styles For Types (Photoplay).

1934 Suggested make-up for movie stars (Photoplay). Movie stars were popular types on which to base a make-up regime.

1935 Let Your Perfume Reflect Your Personality (Modern Screen).

1936 Elizabeth Arden face powder and make-up chart for a range of dress colours.

1937 Lady Esther. Create a New “You”.

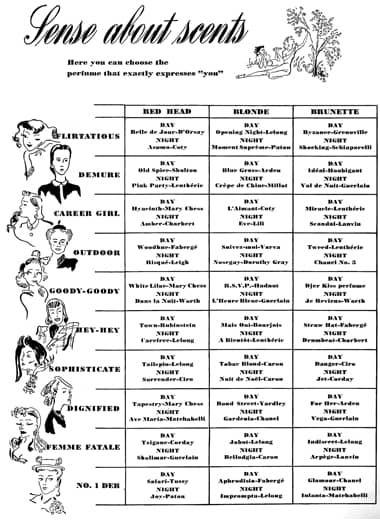

1941 Selecting perfumes by type.

1941 Woodbury Merle Oberon – Ivory Skin Type. Although Woodbury was using a strategy similar to Max Factor they used skin rather than hair to create their types. They also emphasised its dramatic aspect.

“To PLAY leading lady in Love’s drama—heed Hollywood directors. They say: ‘It’s skin, not hair, that determines type.’ That’s why they divide all beauty into five skin types. You are one of them.”

1949 Max Factor Lipsticks in shades suitable for the each of his four colour types.

2015 Clinique. Types are still used occasionally to sell make-up. Clinique’s recent ‘What’s Your Line?’ used a number of types – including Natural, Sophisticate, Flirt, Bombshell, Starlet and Superstar – to differentiate its eye make-up.