Corrective Make-up (Concealers)

Many forms of make-up can hide skin blemishes and pigmentation irregularities. In the 1920s, for example, women with marked suntan lines could disguise them with a liquid powder or powder cream.

See also: Liquid Face Powders and Powder Creams

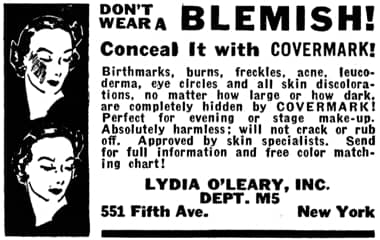

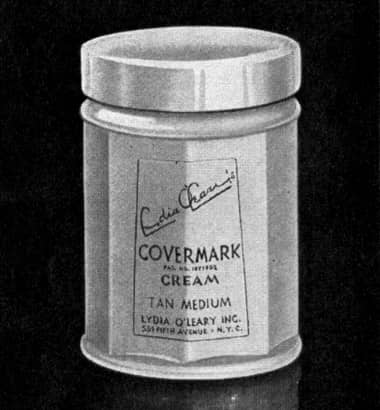

Towards the end of that decade, make-up specifically designed to conceal – now called camouflage make-up – was developed by Lydia O’Leary. Called Covermark, it could be used to cover larger skin blemishes such as prominent birthmarks, rosacea, varicose veins and large scars. Prior to this, the only commercial make-up that would cover these serious skin blemishes was greasepaint.

See also: Greasepaint and Covermark

Following the introduction of Covermark a number of other firms – most notably Clark-Milner’s – entered this market but sales of camouflage make-up were not large enough generate much interest from any of the major cosmetic companies.

As well as its small customer base, individuals using camouflage make-up had to be educated about the correct way to apply it to produce a pleasing result. This needed more expertise than was generally available from a department store beauty demonstrator or salon beautician. Lydia O’Leary was well aware of this issue and personally trained many women in the art. However, she was also a business woman and tried to widen the market for her products by suggesting that Covermark Cream could be used for more common problems such as dark circles under the eyes – one of the main uses for modern concealers. In 1936, she also introduced Spot-Stik, a stick form of Covermark specifically designed to be used by the general public for hiding minor skin blemishes. This means that Covermark is generally regarded as the first modern concealer.

Camouflage make-up was always going to be a niche product of little interest to the majors. Apart from individuals with major skin blemishes the only other group likely to use camouflage make-up were morticians. The idea of a concealer opened up greater possibilities and some of the majors added them to their make-up lines. Helena Rubinstein, for example, introduced Conceal in 1942, a cream that came in two shades (light and dark) to be used under regular make-up. On the whole, these products were only used to cover blemishes. This changed with the arrival of Ayer Magic.

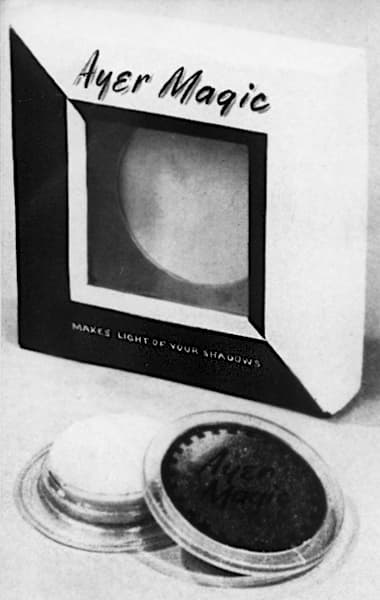

Ayer Magic

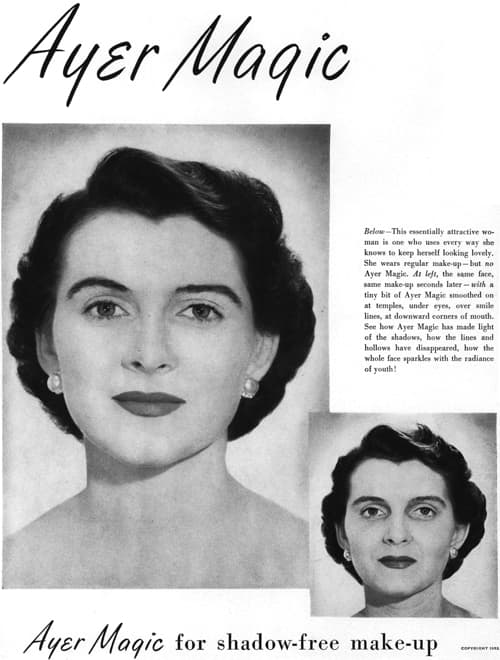

In 1952, Harriet Hubbard Ayer released Ayer Magic, a cream concealer. This ‘Shadow-Free Make-up’ – described as being the result of 20 years of research by the Hollywood make-up artist Kiva Hoffman [1903-1978] – used facial contouring practices employed by make-up artists in the film industry.

Ayer Magic is an new product and the key to the new Shadow-Free Make-up. Ayer Magic is light … light ln creamy form. It is applied to the shadows and hollows of the face … and the shadows and hollows seems to disappear. It gives the effect of perfect lighting on the face constantly!

(Harriet Hubbard Ayer Advertisement, 1952)

The product was applied over foundation along smile lines, under the eyes, down the corners of the mouth, and across the temples and then blended in with a foam sponge.

Apply your regular foundation but not your powder; moisten your own forefinger, clip a sparing amount of Magic cream and apply to the downward corners of your mouth, over the smile lines, under the eyes and at the temples. Blend Ayer Magic carefully into your foundation till it disappears, with the miniature airfoam sponge you will find in the box. Then apply your powder. Now look in the mirror, you won’t believe the difference!

(Harriet Hubbard Ayer Advertisement, 1952)

Advertising for Ayer Magic suggested that it would make you look 10 to 15 years younger. By advertising Ayer Magic in this way – rather than just for hiding blemishes – Harriet Hubbard Ayer opened the door to a wider customer base for concealers.

Above: 1952 Before and after photographs for Ayer Magic.

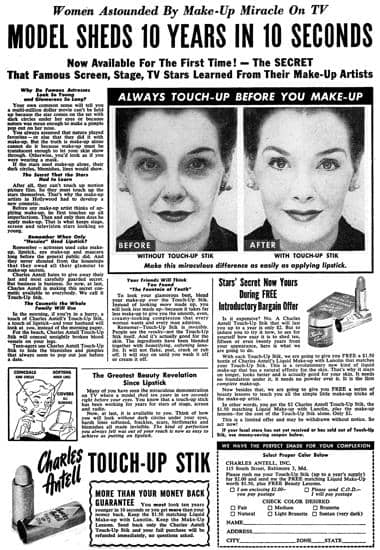

Following Ayer Magic, three new concealers were introduced into the American market in 1954: Charles Antell’s Touch-Up Stik, Max Factor’s Erace and Westmore’s Beauty-Stick. Unlike Ayer Magic, all of these concealers were produced as sticks and all were promoted through the new medium of television, with Charles Antell being particularly adept at using television advertising to best effect.

Charles Antell

Above: 1953 Leonard Rosen (front left), Charles Kasher (front), and Julius Rosen (front right) from Charles Antell each holding a hair-care product. In 1955, Charles Kasher sold his shares in Charles Antell to Leonard and Julius Rosen and went to work in advertising. The Rosen brothers later turned to real estate.

The heads of the Charles Antell company – Charles Kasher, Julius Rosen and Leonard Rosen – were big believers in television. Hazel Bishop’s Lasting Lipstick (1950) had achieved astonishing sales using television advertising and the Charles Antell Company had already used hard sell television and print campaigns to promote Charles Antell Formula No. 9 for the hair, Charles Antell Shampoo, and Charles Antell Hexachlorophene Soap earlier in the decade.

See also: Hazel Bishop

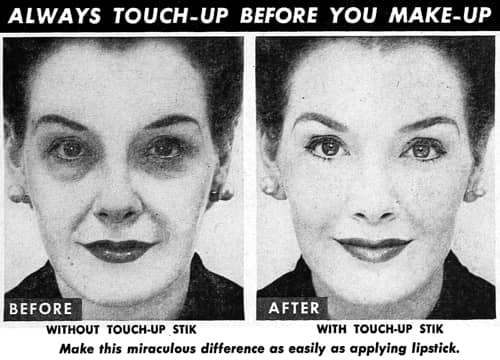

Despite receiving a ‘Cease and Desist’ order from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for many of its dubious product claims (Docket 6102, FTC, 1953) the executives of Charles Antell were not deterred and used similar tactics to promote its new Touch-Up Stik concealer. Their catchy tag line for Touch-Up Stik was ‘Always Touch-up before you make-up’.

Above: 1954 Before and after photographs for Touch-Up Stik.

Advertisements for Touch-Up Stik mentioned common blemishes like spider veins and pimples but, like Ayer Magic, Antell concentrated more on showing how the concealer could make you look younger by covering blemishes such as the dark areas around the eyes. Their sales pitch was made easier by the fact that concealers were an ideal product to sell through black and white television.

[T]elevison is a particularly dramatic and convincing medium for a product of this type. The model walks in front of the camera, looking haggard and tired; then, in front of one’s eyes, in the course of only a few seconds, she becomes many years younger-looking and infinitely more attractive.

(Sagarin, 1954, p. 233)

Max Factor’s marketing for Erace also targeted dark circles under the eyes and use a similar tag: ‘The cover-up used before make-up’. With all the television advertising it is easy to see why sales of stick concealers rose from thousands to millions of units in the United States in 1954. Although they may not have lived up to all that they promised, and repeat business was lower than hoped for, concealers now became part of many women’s make-up routines. The fact that stick concealers looked like lipstick and could be carried around in a purse to be applied when needed, only added to their appeal.

Formulation

Concealers in the 1950s – creams or sticks – were similar to foundations, only made more opaque. This was usually achieved by adding higher levels of titanium dioxide to the base. As the titanium dioxide is white, additional pigments – both inorganic minerals and lakes – were required to achieve a suitable shade. The higher levels of powder could lead to adsorption of air during grinding but his issue could be managed through the addition of ingredients that reduced surface tension and by carefully controlling the manufacturing process (Hilfer, 1953, p. 619).

Base

Cream concealers could be made using a base of petrolatum, mineral oil and paraffin but stick forms required the addition of extra waxes such as beeswax, ceresin, carnauba and/or candelilla wax. A recipe for a stick concealer is given below:

% Castor oil 29.4 Butyl stearate 14.0 Petrolatum, short fibre 5.6 Beeswax, yellow 10.5 Ozokerite, m.p. 85-88°C. 7.0 Paraffin, m.p. 54-58°C. 3.5 Titanium dioxide 25.0 Pigment–magnesium carbonate 5.0 Perfume q.s. Procedure: Heat the oils, fats, and waxes until homogeneous. Add the powders and pass the mixture through a colloid, ointment, or roller mill. Heat the mixture and stir slowly until all of the air is evacuated, and then pour into molds. The mold should be chilled to get greater contraction. It may also be necessary to use a mold release agent if the product has a tendency to adhere to the mold. To this end the molds may be coated either with a silicone mold release or a polyvalent fatty acid ester.

(Feilder, 1957, p. 270)

Colour

As with powders and foundations, a range of colours is needed so that the concealer could be matched to a person’s complexion. However, as they were used in conjunction with other forms of make-up the match did not have to be perfect and most concealers produced in the 1950s only came in 4-6 shades, well short of the range in Lydia O’Leary’s Covermark camouflage make-up.

A later development was the introduction of neutralising concealers. These were based on the idea that undesirable skin shades could be neutralised with a concealer of a complementary colour; e.g., green will neutralise redness and yellow will neutralise purple blotches. Marvin G. Westmore [b.1934] – the son of the make-up artist Monte Westmore [1902-1940] – suggests that this idea goes back to the 1920s but does not recommend the practice for everyday use.

Color theory tells us that when any two colors are mixed, the result is a third color. Mixing opposite colors on the color wheel, e.g., green and red, blue and orange, or yellow and purple, results in an unattractive grayish-green-brown color. This changes the intensity of the two colors and causes them to become dull. The cosmetic industry calls this neutralizing.

The makeup neutralizers/undertoners that are offered—green to neutralize redness, lavender to neutralize sallowness—do nothing more than create a third color, they do not create a skin color. This third color must then be concealed with a color that matches the skin, which adds an extra step and additional thickness to the makeup, not to mention the possibility of dirty-looking makeup.(Westmore, 2001, p. 409)

Medication

Another variation in concealers was the addition of medication. Pimples are a perennial issue for many young women and make-up was used by them to cover them. When cosmetic companies got more interested in the youth market in the 1950s and 1960s many created make-up lines specifically for this demographic and, on occasion, medication was added to concealers. However, this meant that they were now classified as drugs and were subject to greater regulation.

Some pimple cures that were not make-up, such as Clearasil, worked from the other direction and made some attempt to hide themselves by adding colour to their formulation.

Recent developments

Concealers are now available in a myriad of forms. Cream concealers come in pots and tubes and stick concealers are sold in sizes that range from large crayons through to fine pens. A more recent development has been the creation of powder concealers. In the 1960s, the ability to create very fine powders led to the development new forms of powdered make-up – eyeshadows, blushers and blending powders – that were applied with some form of brush or sponge. This led to brush-on ‘mineral make-up’ which some manufacturers claim has a concealing power equivalent to camouflage make-up.

See also: Corrective Make-up (Contouring)

First Posted: 2nd March 2016

Last Update: 19th January 2021

Sources

Draelos, Z. K. (1990). Cosmetics and dermatology. New York: Churchill Livingston.

Feilder, J. G. (1957). Foundation makeup. In E. Sagarin, E. (Ed.). Cosmetics: Science and technology (pp. 262-270). New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

Hilfer, H. (1953). Blemish-hiding creams. Drug and Cosmetic Industry, 73(5), 619, 712.

Sagarin, E. (1954). Letter on cosmetics from overseas. The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record, July, pp. 232-234.

Westmore, M. G. (2001). Camouflage and makeup preparations. Clinics in Dermatology, 19, pp. 406-412

1935 Lydia O’Leary Covermark Cream.

1936 Lydia O’Leary Covermark Cream. Shades: Flesh, Pink Medium, Tan Medium, Dark Olive, Peach, Brunette, Dark and Sun Tan.

1936 Preferred Chemical Blemish Concealer.

1936 Clark-Milner Hide-It Cream.

1937 Clark-Milner Hide-It in cream and stick form. Shades: Light, Medium, Brunette and Suntan.

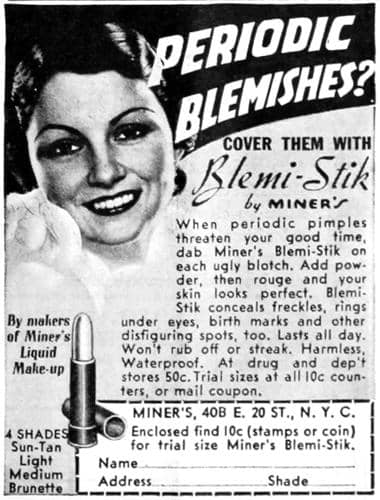

1937 Miner Blemi-Stik. Shades: Light, Medium, Brunette and Sun-Tan.

1938 Lydia O’Leary Spot-Stik. Shades: Light, Medium and Dark.

1943 Kay Preparations Formula 301.

1952 Ayer Magic.

1953 Ayer Magic cream concealer.

1954 Charles Antell Touch-Up Stik. Shades: Fair, Natural, Medium, Light Brunette, Brunette, and Suntan.

1954 Max Factor Erace. This concealer was produced as part of Max Factor’s development of make-up for RCA compatible colour television. Shades: Fair, Natural, Medium, Deep Natural, Tan, and Deep Tan.

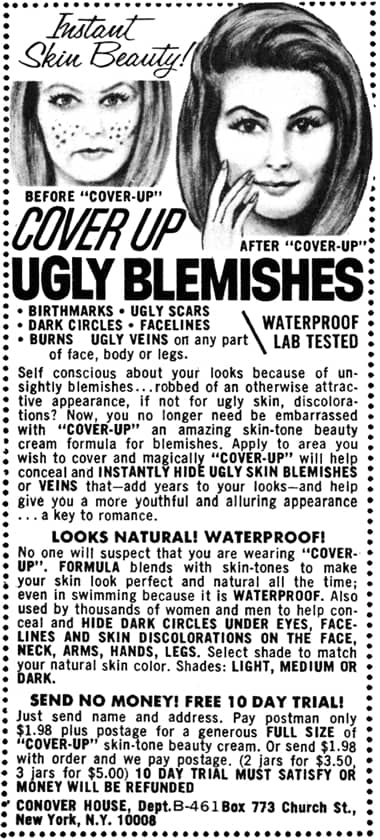

1971 Conover House Cover-up blemish concealer.