Powder Creams

Women who found that their face powder did not stay in place often applied a light coating of vanishing cream before powdering to help the powder stick to their skin. Vanishing creams could be made to look more attractive in the jar by tinting them with an oil-soluble dye like alkanet or a water-soluble dye like eosin. They could also be coloured with pigments and lakes to match the colour of the face powder applied over them. If enough powdered colour was included this would add an extra layer of coverage which could be useful to someone with blemished skin.

The stearate creams, so called day cream, and vanishing creams, and the many variations … are favoured because they are rapidly absorbed by the skin, and so provide a foundation for the application of face powders. … In some instances a cream is simply coloured to match the face powder or compact. On the other hand the cream may be tinted for the colour scheme, for the perfume, or, to supply a particular delicate blush.

(The colour in beauty creams, 1928. p. 383)

Although creams coloured with sufficient powdered pigments and lakes could help reduce visible flaws in a complexion, some manufacturers went further than this, suggesting that their ‘powder cream’ could replace the use of face powder altogether, thereby reducing two operations into one.

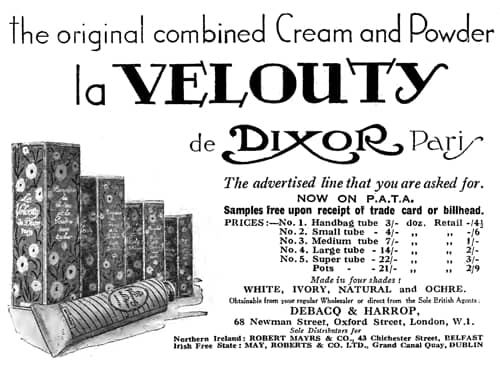

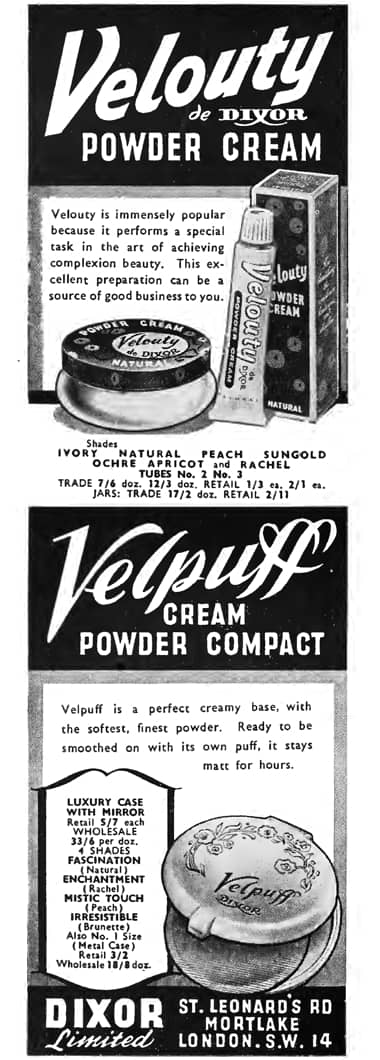

Above: 1931 Dixor Velouty Power Cream. This French company claimed to have made the first powder cream.

Although interest in powder creams peaked in the 1930s, a number of cosmetic companies made them up to and after the Second World War. They were sold under a variety of names with the terms ‘powder cream’ and ‘foundation cream’ being the most common; powder cream being more likely in Britain and foundation cream more usual in the United States. Unfortunately, there was no standard usage for either of these terms. Wells & Lubowe (1964) even distinguish between them.

Foundation Cream is a cream for day use. Its purpose is to provide a semi-matt, non-drying, sufficiently tacky “undercoat” film for superimposed face powder. Its color/pigment content is usually quite small, in the region of 2 to 5 per cent. (Some so-called Foundation Creams nevertheless more closely resemble the Powder Creams or even the Cream Make-Ups, in having a higher or much higher color/pigment content.)

Powder Creams represent an early attempt to combine creaming and powdering in a single operation, or at least to reduce the time and effort spent on subsequent powdering. Some powder creams are still on the market. They rate a pigment/color content of 10 to 20 per cent; rarely more.(Wells & Lubowe, 1964, p. 88)

Formulation

Most powder creams sold before the Second World War were made using some form of stearate, glycol or glycerol stearate vanishing cream.

A general formula for a powder cream:

per cent Vanishing cream 70.0 Talc 24.0 Titanium dioxide 5.5 Perfume 0.5 Color to suit.

Procedure: Make the vanishing cream in the usual way. Mix the talc and titanium dioxide and color and perfume. Add the cream and then run the entire mass over a roller mill.(Chilson, 1934, p. 308 )

Powder cream made with diglycol stearate vanishing cream:

parts Diglycol stearate 100 Water 300 Preservative q.s. Melt and mix at 170° F. and when thickening pour into Powder base 150 Glycerin 180 Colour q.s. Perfume q.s. (“Powder Creams,” 1939, p. 152)

Powder creams did not require any special machinery to make them and could be produced with equipment already employed in the manufacture of face powders and creams. However, they could not be made by simply mixing a good quality face powder into a vanishing cream. Dry powdered colours looked different when incorporated into a cream, so shade formulas required adjusting, and some ingredients – such as carbonates and zinc salts – had to be removed to avoid adverse chemical reactions when the powder and cream were combined.

Stearic acid: Vanishing creams normally contain free stearic acid which can react with any magnesium, calcium or zinc carbonates present in the powder. Most cosmetic chemists recommended leaving them out altogether or suggested they be substituted for with Osmo-Kaolin, colloidal china clay and/or amorphous silica.

Zinc salts: The white pigment zinc oxide had to be avoided in powder creams as it was known to chemically react with some emulsifying agents used in vanishing creams of the time, e.g., Tegin. In its place cosmetic chemists recommended titanium dioxide which was more chemically inert and had the added bonus of a greater covering powder.

Powder creams had relatively low levels of colour; much lower than the highly coloured make-up in use today. High levels of powder could not be used as they could destabilised the vanishing cream emulsion causing the oil and water parts to separate and the powder cream to ‘crumble’. This would also make it harder to spread the powder pigments uniformly across the face which would make the face look blotchy. Max Factor, for example, recommended that his Make-Up Foundation Cream – in White, Flesh, Rachelle and Natural shades – be applied very sparingly and blended well in.

Apply a small dab, half the size of a pea, of Max Factor’s Make-Up Foundation Cream to forehead, cheeks and chin. The less used, the more perfect the make-up. Now blend the Make-up Foundation over the skin until it seems to disappear. Blend away from the centre of the face. Wipe away any surplus. Dry with a tissue. The skin will retain sufficient foundation to hold the make-up for hours.

(“The new art of society make-up,” 1937)

Above: 1941 Blending Foundation Cream into the face with the fingers. To help get an even spread, some powder creams were applied with a sponge or were two-in-one, that is, they could be applied with the fingers or a sponge.

The low levels of pigment, and their restricted shade ranges, meant that most powder creams were used as an adjunct to, rather than a substitute for, face powder.

Other types of powder creams

Although most powder creams used an oil-in-water vanishing cream, others were made using some form of water-in-oil cream – such as a cold cream – or were created as water-free fat mixtures. Powder creams made with a vanishing cream base looked matt on the skin but if a water-in oil cream was used the resulting cosmetic had more lustre. These water-in-oil powder creams got a boost in the American market in 1934 when Dawn of Hollywood Inc. bought out Luminous Dawn and ushered in a vogue for shiny make-up.

Anhydrous (water-free) powder creams do not really deserve to be grouped with those made with oil-in water or water-in-oil emulsions. Anhydrous forms were not emulsions, so technically were not creams, and they could be made with much higher levels of colour so could easily function as a finished make-up.

After the Second World War powder creams continued to be sold but their use declined as new and better make-up bases came on the market. A case can be made that they morphed into something else. Pan-cake make-up (1937) has been described as a dehydrated powder cream and the newer pressed cream powders – epitomised by lines such as Pond’s Angel Face (1946) – also show some affiliations with them.

Updated: 30th July 2018

Sources

Allen, G. H. (1935). Cream and liquid face powders. The Manufacturing Chemist. December, 397-398.

Avis, H. W. (1933). Powder creams. The Manufacturing Chemist. December, 363-364, 373.

Chilson, F. (1934). Modern cosmetics. New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

The colour in beauty creams. (1928). The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record. September, 382-383.

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston, MA: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.

Harry, R. G. (1944). Modern cosmeticology (2nd ed.). London: Leonard Hill.

Hilfer, H. (1952). Foundation creams and lotions. The Drug and Cosmetic Industry. October, 466-467, 557.

The new art of society make-up [Booklet]. (1937). London: Max Factor Studios.

Redgrove, H. S. (1933). Powder creams. The Manufacturing Chemist. March, 77-79.

Powder creams. (1939). Manufacturing Perfumer. May, 512-513.

Wells, F. V., & Lubowe, I. I. (1964). Cosmetics and the skin. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

1923 Dixor Velouty Powder Cream. Dixor suggested it could be used instead of a liquid powder on the hands arms and shoulders as well as on the face.

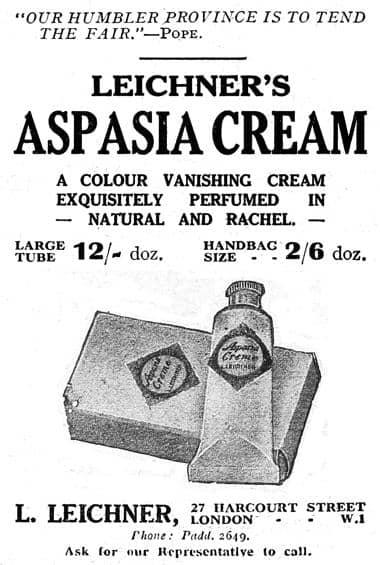

1926 Leichner Aspasia Cream. Shades: Natural and Rachel.

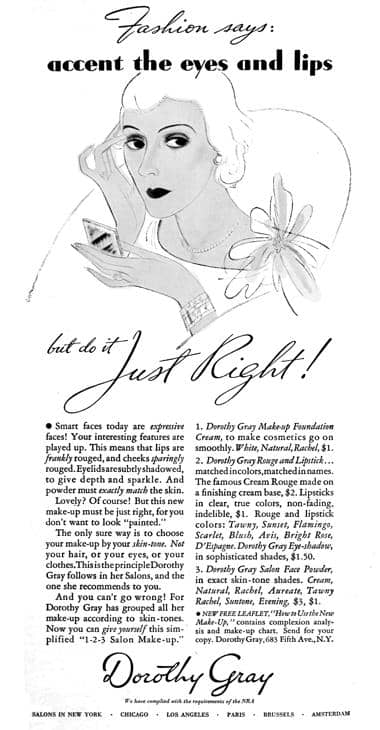

1934 Dorothy Gray Make-up Foundation Cream. Shades: White, Natural and Rachel.

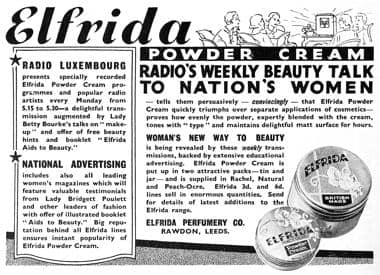

1937 Elfrida Powder Cream. Shades: Rachel, Natural and Peach-Ocre.

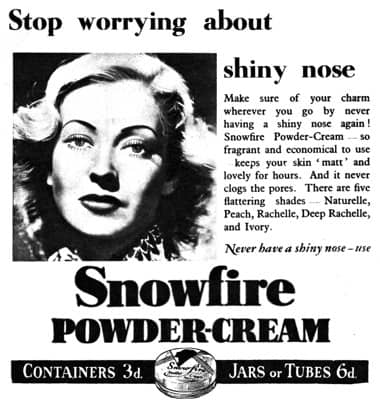

1938 Snowfire Powder Cream. Shades: Naturalle, Peach, Rachelle, Deep Rachelle and Ivory.

1949 Potter & Moore Powder-Cream.

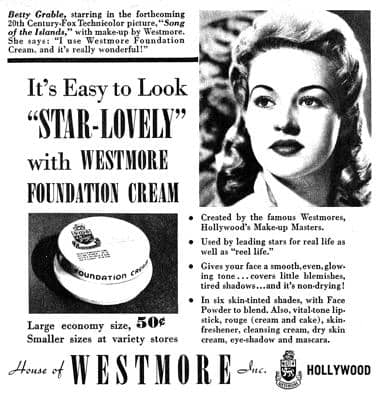

1942 Westmore Foundation Cream. Shades: Natural, Coral, Continental, Castilian, Rose Glow and Copper.

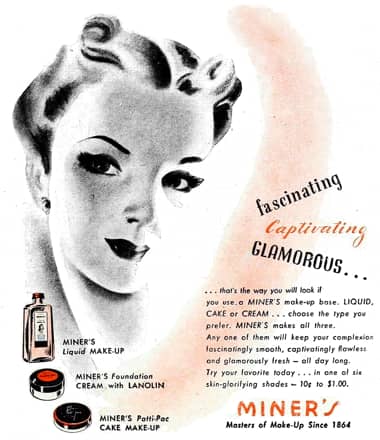

1943 Miner’s Foundation Cream.

1960 Dixor Velouty Powder Cream and Cream Powder Compact.