Electrolysis

Nineteenth-century physicians knew that hair grew from a ‘pulp’ at the base of the hair follicle and that eliminating it would permanently remove the hair. A variety of methods were used to destroy the ‘germinal papilla’ including hypodermically injecting carbolic acid, twisting barbed needles (Hinkel & Lind, 1986, p. 150) and inserted needles heated with red-hot curling irons (Wagner, Brysk & Tyring, 1997, p. 949). These methods were crude at best and usually resulted in visible scars.

A new treatment

Ophthalmologists of the time were also interested in permanently removing hair. Ingrown and other aberrant eyelashes could irritate the eye, resulting in chronic inflammation and even blindness. Dr. Charles Michel was one such ophthalmologist and he tried removing aberrant eyelashes with heated needles, surgery and twisting needles but found that they all produced unsuitable body reactions and scarring. Eventually, he modified a process which had been previously used in general surgery – chemical decomposition through electricity – known as electrolysis or electro-coagulation. He connected a gilt needle to the negative electrode of a battery, inserted the needle into the hair follicle of the eyelash, applied a current for a few seconds and successfully killed the hair follicle with the sodium hydroxide (lye/caustic soda) produced at the negative electrode.

The agent employed is electricity, (a constant current battery of 8 to 20 medium sized cells is all-sufficient) the form, electrolysis. I simply pass a fine, gilt needle into the hair follicle and allow the current to produce the electrochemical decomposition of it and its papillae.

(Michel, 1897, as reported in Wagner, Brysk & Tyring, 1997, p. 947)

Following his success with eyelashes, Michel also used the technique to permanently remove eyebrow hair and then published a report detailing his electrochemical decomposition of hair follicles in the St. Louis Clinical Record in 1875. After reading Michel’s report, the editor of the journal, Dr. William A. Hardaway [1850-1923], decided to try the technique in his own practice. Using Michel’s procedure, he successfully treated patients with excess body hair and presented his results at the second meeting of the American Dermatological Association.

After this, other physicians took up the practice and the treatment spread. At first, the hair was removed before the follicle was destroyed but, in 1882, the dermatologist Charles Henry Fox began practicing electrolysis with the needle introduced alongside the hair (Colwell, 1922, p. 89), the practice commonly employed to this day.

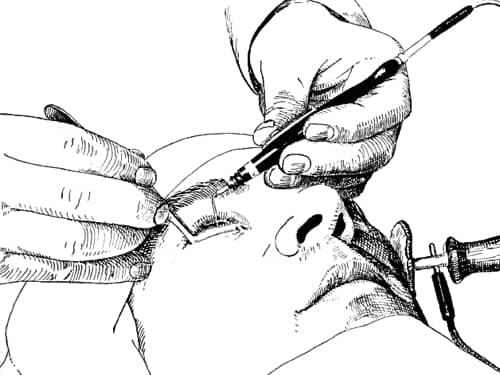

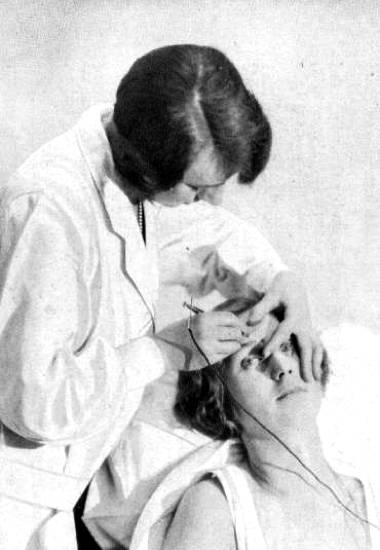

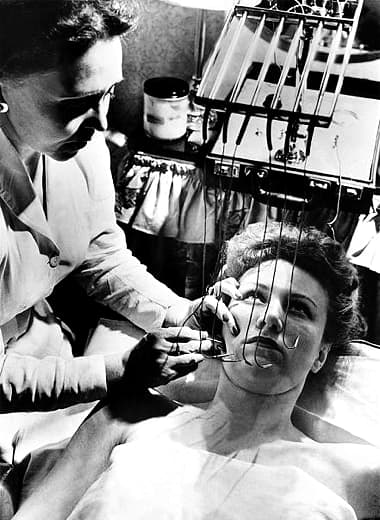

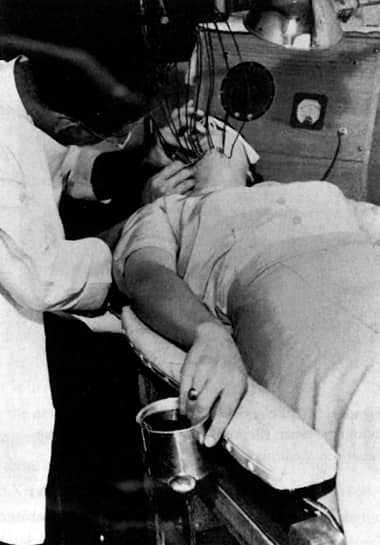

Above: 1915 Using electrolysis to remove an eyelash. Note the positive electrode placed against the cheek of the patient.

Even after electrolysis had become widespread some retured to non electrical practices. For example, in 1894, John H. Woodbury [1851-1909] suggested using fine needles tipped with some sort of corrosive liquid to kill hair follicles in place of electricity.

My latest method of removing superfluous hair consists, first, in the application of a powerful, penetrating fluid to the base of each strand of hair or external aperture of each hair follicle. By means of a very fine needle, whose point has been wet with the same solution, I open and at the same time penetrate the follicle, thus allowing the fluid to come in direct contact with the nutrient blood-vessel and nerve of the hair bulb, instantly destroying them and rendering it utterly impossible for another strand of hair to grow from it. The operation is somewhat lengthy, it is true, because each follicle is separately treated, but the good results obtained and the comparative freedom from pain are a sufficient compensation for the length of time.

(Woodbury, 1894, pp. 116-117)

See also: Woodbury

Early electrolysis machines

The electrolysis machines developed by Michel, Hardaway and others were battery operated, generating what medical practitioners of the day called a ‘galvanic current’, named after Luigi Galvani [1737-1798]. Many nineteenth-century physicians were familiar with galvanic batteries and electro-therapeutics, so it was relatively easy for them to set up a working electrolysis machine. If the necessary parts were not available in their surgery, they could be easily obtained from a medical supplier.

See also: Galvanic Treatments

As the use of electrolysis grew, some manufacturers combined all the required parts into complete kits containing a battery along with all the necessary cords and electrodes and advertised them in their catalogues. To make them easier to use, detailed instruction manuals were often included which outlined the processes involved in removing hair by electrolysis.

Schall & Son London

No 675. Complete set for epilation, consisting of 9-cell battery with collector inserting the cells one by one bracelet electrode No. 412, needle-holder No. 664, forceps No. 666, a packet of needles and collecting wires £3.0.0

Explicit directions for use are sent with this outfit.(Schall & Son, 1913)

Lay operators

Manufacturers were naturally keen to sell as many electrolysis machines as possible. Street/mains electricity was absent from most cities in the early part of the twentieth century but as the equipment was battery powered, and very portable, this was not an issue. In addition, their operation was not regulated so, before long, these electrolysis machines were being used by individuals outside the medical profession. The attitude of many physicians helped. Some doctors could see the distress that excess hair was causing their patients but others viewed electrolysis mainly as a beautifying practice – the correction of a ‘cosmetic defect’ rather than a cure for a ‘serious disease’ – and discounted it as a medical procedure, leaving it to others to provide the service.

By the end of the nineteenth century, electrolysis treatments could be readily obtained from a number of non-medical practitioners – both men and women – including specialist operators, as well some barbers, hairdressers and beauty specialists. These lay operators also adopted other medical uses for electrolysis and began treating other facial blemishes such as moles, warts, spider veins (telangiectasia), birthmarks, pimples, blackheads and acne. Some branched out even further and became Beauty Culturists. Marie Earle and Jeannette Scalé (Mrs Pomeroy) are two examples of beauty businesses appear to have started this way.

Superfluous hairs on the face can only be really eradicated by electrolysis, and those who wish to undergo this little process should always be most careful to go to a qualified person. I can most thoroughly recommend Mrs. Pomeroy, 29 Old Bond Street, for the removal of these and other facial blemishes in a skilled and competent manner.

(Browning, 1898, pp. 216-217)

See also: Mrs. Pomeroy and Marie Earle

Beauty salons that did not start up offering electrolysis, such as Helena Rubinstein, soon introduced the treatment as it was a valuable source of clients and revenue.

See also: Helena Rubinstein

Operator skill

Despite the helpful literature supplied by manufacturers, practitioners (both lay and medical) soon realised that using the machines to produce satisfactory results without scarring or pitting the skin was not a simple matter – skill and experience counted.

In no operation where human life is not involved does experience count for more than it does in this comparatively simple and easily executed procedure.

Whenever it is possible to watch the operation as performed by an experienced cosmetiste, it is advisable that this should be done. There are many little points in the technic of the operation that contribute materially to its success which can be better mastered by observing the operation than reading any description of it.

It is recommended that the beginner attempt the removal of hair on portions of his or her own body rather than the face and that no attempt be made on the face until the student is sure that he understands at least the working principles of electrolysis. Only partial experience can be gained in this manner however.(W. M. Meyer, 1936, p. 349)

Concern about the expertise of operators came from a number of sources: legislators, manufacturers, the medical profession and lay operators were all interested in this area. In France, lay operators were banned and patients were required to seek medical assistance. In the U.S. and Britain the situation was more open. As lay operators became more common, some authorities began to regulate the practice but this varied from country to country and from state to state. The arrival of professional associations and training schools helped set standards and supervised training programs. Manufacturers were also an important source of training. For example, when multiple-needle electrolysis machines were introduced, the company set up to manufacture them also trained operators in their use.

Limitations of electrolysis

Although electrolysis was a significant improvement over previous treatments it had a number of problems. Some of these were due to the technical limitations of the equipment used, others were inherent to the method. As well as introducing the possibility of infection, the process was very slow, often painful, could produce noticeable scars if rushed or done incorrectly, and/or create pigmentation problems in the treated areas of some clients. Patient forbearance, variation in skin and hair types, operator fatigue, acuity of vision and the cost of treatments were all factors affecting the successful outcome of a treatment regime. The fact that patients endured all these drawbacks gives us some idea of how desparate they were to get rid of the unwanted hair.

Treatment times: Electrolysis was inherently slow. Even skilled operators had to wait for the production of sufficient sodium hydroxide to destroy the papilla. The process could be speeded up with a stronger current but this increased the risk of scarring – an ongoing problem. Removing the needle too early would only lead to regrowth.

An experienced operator could probably average removing about 60 hairs an hour, although this depended on whether hair was being removed from lip, cheeks, chin or neck. Patients with difficult hairs would have lower removal rates.

One way around this problem was suggested by the father of demabrasion, the German dermatologist Ernst Kromayer [1862-1933] in 1908 – use multiple needles. However, for individuals with severe problems, treatments could still go on for months or longer.

Multiple-needle electrolysis

A 1909 report of Kromayer’s technique described the process:

Usually electrolytic epilation is performed with one needle at a time, but he [Kromayer] sees no reason why several may not be employed simultaneously. He therefore has his needles connected with 15 cm. of the thinnest copper wire, which can be brought in contact with the copper wire of the other needles. Having formed a bundle of such needles,he seizes each one in rotation by artery forceps and inserts it into the hair follicle. When all the needles required are in place the wires are connected with the battery and the current turned on. In applying a number of needles simultaneously it is necessary to adjust the current according to the number of needles acting. It has been found that a current of 5 milliamperes destroys a hair completely in one minute. The complete destruction of the hair can be ascertained by pulling lightly on the hair shaft. The hair will be found to be held tight. On pulling somewhat more strongly, the hair comes away and is found to end sharply, as if cut off. No trace of the hair bulb may be found,as this should have been destroyed by the electric current. Before the process is complete a hardening around the needle is felt, and soon a definite nodule is seen. If this nodule begins to be transparent, it is time to remove the needle, as there is danger of the cutis becoming involved in the necrosis and of the skin “burning through.” If five needles are applied at one time the current will be divided into fifths, and it will therefore be necessary to allow a 25 milliampere-minute current to act. It is wise to apply the strongest current well tolerated, and the author usually begins with 1 milliampere, and increases this up to 5, 10, 20, and 40. The highest he has used was 50 milliamperes. It must be remembered that the stronger the current the shorter will be the time during which it is necessary to apply the current to destroy the hair bulb. … At times he finds it wiser to use only a few needles, for example five, and to apply them continuously. After one has done its work on one hair bulb it is withdrawn, and is inserted into another follicle, and so on. In this way there are always five needles acting.

(An epitome of current medical literature, 1909, pp. 83-84)

The multiple-needle technique seems to have been used in some European salons before the war. Helena Rubinstein looks to have introduced it into her Paris salon in 1914.

See also: Helena Rubinstein

Kromayer’s idea was taken up by Professor Paul M. Kree [b.1888] in the United States. In 1918, he patented a multiple-needle electrolysis machine (US: 1445961), established a business to manufacture them, and a school to teach the technique.

See also: The Drilling Machine

Scarring: Applying a current for too long could result in the development of a visible scar. Practitioners would sometimes curtail the application of electricity but this could reduce their success rate and lead to regrowth. Ernst Kromayer had a suggestion for this as well and recommended that insulated needles should be used.

Kromayer states that the ordinary method of destroying hairs by electrolysis has the disadvantage of producing a scar which remains visible. In order to limit this unsightly appearance it is usual to interrupt the process before the hair is completely destroyed, and in this way so-called “recurrences” are frequently seen (Deut. med. Woch., December 24th, 1908). Even when the superficial layer of the hair bulb is destroyed the hair may grow again. He therefore considers that it would be better if the whole process could be carried out subcutaneously, so that it would not be necessary to interrupt the action until the hair was completely and finally destroyed. For this purpose he has constructed electrolytic subcutaneous needles, which are coated up to within from 2 to 10 mm. of the point with varnish. This coating is so thin that it does not hinder the introduction of the needle.

(An epitome of current medical literature, 1909, pp. 83-84)

Time: The length of the treatment session was also a limiting factor. Sessions were generally between a half and a full hour. Even if the patient could continue, treatments rarely lasted longer, as the operator would become fatigued. This meant that very few hairs were removed at each sitting. Given that some removed hairs grew back, patients were often discouraged by a perceived lack of progress and it was necessary to reassure them that progress was being made.

As has already been hinted, there occur times of discouragement, and these times are sure to come if you have not forewarned your patient that some hairs will return. You must remember that your patients are morbid on the subject of what they consider a facial blemish; so much so that they are determined to have you remove all of the lanugo hairs that may be found upon the face. Again, they forget their appearance when they first came to you.

I have had patients come into my office and tell me that the work was a failure, that all the hairs removed had returned, and they, to say the least, were very much dissatisfied; almost without exception I have been able to convince them that their condition was much better than when they first came to me, and that it would require but comparatively little work to make the operation a complete success. These patients have subsequently become my warmest supporters.

Were it possible to prevail upon patients to have a photograph taken before the operation of the part of their face where the growth had been, the comparison would aid very materially in overcoming the discouragement. In every case we can absolute promise that eventually every hair will be permanently removed.(Hayes, 1904, pp. 81-82)

Pain: Patients showed a range of tolerance to pain. The pain generated also varied depending on the area of the body undergoing treatment.

In early machines, the galvanic current was produced by cell batteries and regulated not by a dial (rheostat) but rather by connecting more or fewer cells to the circuit. Voltage regulation was limited and the intensity of current used was higher and therefore more painful. Later machines did show improvements with the addition of regulating devices (rheostats), amperage meters and the use of mains electricity but there was no way to avoid the production of sodium hydroxide and the associated pain.

Needles were also an issue. They were not the thin, disposable needles in use today. Platinum and gold needles were expensive and tended to deteriorate with reuse, so steel was preferred. Some commercial operators used thick sewing needles to reduce costs but even electrolysis needles purchased though supply companies were much thicker than those currently in use, adding to patient discomfort.

Some physicians tried topical anaesthetics such as cocaine to reduce the pain with mixed results.

Dr. A. D. Rockwell, of New York, said … he had employed cataphoresis extensively in the removal of hair, and had found that by using cocaine cataphorically this ordinarily uncomfortable treatment could be applied without causing any pain. Recently, however, during the application of cocaine in this way the patient suddenly became unconscious, and was at first thought to be dead, although she eventually recovered. This had made him hesitate to use cocaine as frequently as formerly.

(Transactions of the American electro-therapeutic association, 1899, p. 89)

Commercial operators also tried to minimize the pain but generally steered clear of local anaesthetics.

Should the patient be very sensitive to the electrical current, less pain is produced when the needle is introduced before the current is completed. The patient is then directed to put fingers into the solution, and before the needle is removed, is requested to remove the fingers from the solution. By this means, the slight shock on making and breaking the current is much less than when the needle is introduced without the current having been broken … The needle is however more easily inserted if a small amount of current is on while inserting.

(W. M. Meyer, 1936, p. 346)

Cost: In the early part of the twentieth century a commercial operator in the U.S. might earn between six to ten dollars an hour, more than a day’s pay for many other workers (Herzig, 2008, p. 871) making the treatments out of the reach of many. Treatments could extend over many months so some women were forced to abandon them before completion and return to shaving, depliators, tweezing and other methods of removing unwanted hair, because they ran out of money.

See also: Hair Removers

Cost pressures also had effects on the operators. This was particularly so in the early history of electrolysis, when the technique was slowest. When working on wealthy women, operators could take more time and use lower current levels, thereby reducing the risk of scarring.

“[P]atients whose time and money are limited,” wrote Dr. Sorenson in 1893, “will urge the doctor to take out hairs that are too close together to be operated upon with good results in one day, or even on two successive days … Affluent women were easier to treat than poor women, another physician argued at a gathering of dermatologists, since “We could take our time in treating these cases, using an amperage of low intensity … with less tendency to scarring.”

(Herzig, 2008, p. 876)

Poorer patients tended to pressure operators to use higher current flows and traded off an increased chance of scarring for a larger number of hairs being treated at each session. Fortunately, as the levels of prosperity rose in the twentieth century and new technologies for hair removal arrived this trade off became less of an imperative.

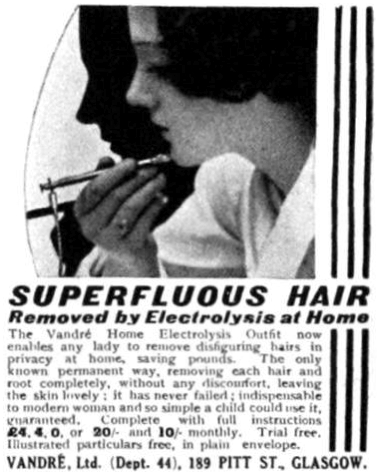

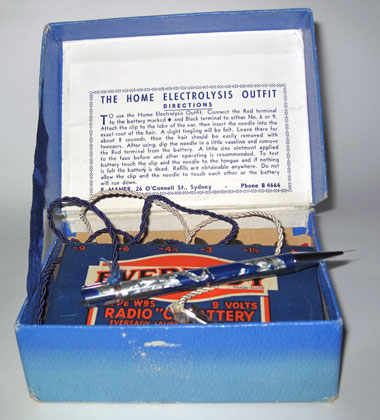

One way to reduce the cost was to treat yourself. Electrolysis units designed for home use were available before the First World War and continued to be advertised right through most of the twentieth century. However, they have a number of problems. First, even if you have a stready hand, good eyesight and a steely resolve, it is not easy to treat yourself in front of a mirror; results are always better if someone else operates the machine. Second, the machines produced for the home market are never as effective as those used commercially. Today, self-treaters recommend the purchase of second-hand commercial machines. Third, even if the needle is correctly inserted timing the current flow incorrectly can result in failure if the timing is too short or scarring of the timing is too long.

One other problem was skin discolouration caused by black deposits produced by a chemical reaction between hydrochloric acid and the metal in the needle if, by chance, the operator used the wrong polarity. The problem was easily avoided by using needles made from gold or platinum alloy, or stainless steel, but some electrologists in the past failed to do this and mistakes happened. Fortunately, this is not an significant issue today.

X-rays

The issues associated with permanent hair removal by electrolysis – cost, pain and time – saw many women opt to have their hair removed with X-rays, with disastrous consequences.

See also: X-rays and Hair Removal

Enelectrolysis

In 1905, in an article to the Lancet, Balmanno Squire outlined an alternative method to the standard procedure. Rather than inserting the needle, applying current, and then removing the hair, he suggested that the hair should be pulled out first and the needle then inserted down the hole left after the hair was extracted. He called his method enelectrolysis. His observations that it less was likely to puncture the wall of the follicle must be tempered by the fact that he used the blunt end of a No. 12 sewing needle during enelectrolysis, whereas doing electrolysis, he had been using the sharp end. His statements that it was more expeditious must also take into account that he suffered from myopia, which presumably made it easier for him to identify the opening to the hair follicle once the hair had been removed. Needless to say his method did not catch on.

Alternatives

Reliable high-frequency machines which killed hair follicles by heat (thermolysis or diathermy) rather than chemical decomposition (electrolysis) came into operation in the 1940s. The new technique removed hairs at a more rapid rate and many practitioners switched from electrolysis to thermolysis or to the later Blend Method which combined electrolysis and thermolysis in the one operation. However, these new methods were not without their own problems and electrolysis remains the preferred procedure for many electrology practitioners today.

See also: Thermolysis and the Blend

First Posted: 17th May 2010

Last Update: 2nd May 2023

Sources

An epitome of current medical literature. (1909) The British Medical Journal. May 22, 1(2525), 81-84.

Browning, H. E. (1898). Beauty culture. London: Hutchinson & Co.

Colwell, H. A. (1922). History of electrotherapy and diagnosis. London: William Heinemann.

Foan, G. A., & Bari-Woolls, J. (Eds.). (n.d.). The art and craft of hairdressing: The standard and complete guide to the technique of modern hairdressing, manicure, massage and beauty culture (2nd ed.). London: New Era Publishing.

Fox, G. H. (1886). The use of electricity in the removal of superfluous hair and the treatment of various facial blemishes. Detroit, MI: G. S. Davis.

Hayes, P. S. (1904). Electricity and the methods of its employment in removing superfluous hair and other facial blemishes. Chicago, Ill: McIntosh Battery and Optical Co.

Hinkel, A. R., & Lind, R. W. (1968). Electrolysis, thermolysis and the blend: The principles and practice of permanent hair removal. Los Angeles, Ca: Arroway.

Herzig, R. (2008). Subjected to the current: Batteries, bodies, and the early history of electrification in the United States in Journal of Social History. Summer; 41, 4. Academic Research Library.

Moler, A.B. (1906). The manual on barbering, hairdressing, manicuring, facial massage, electrolysis and chiropody as taught in the Moler system of colleges.

Müller, R. W. (1916). Hair. Its nature, growth, and most common afflictions, with hygienic rules for its preservation. New York: William R. Jenkins Company.

Schall & Son. (1913). Electro-medical instruments and their management and illustrated price list of electro-medical apparatus. (15th ed.). Stonebridge: John Wright & Sons Ltd.

Squire, B. (1905). Enelectrolysis: An improved method of operating on superfluous hair. The Lancet. 165(4252). 493-494.

Mould, R. F., Robison, R. F., & Van Tiggelen, R. (2010). Louis-Frédéric Wickham (1861-1913): Father of radium therapy. Journal of Oncology. 60(4), 79e-103e.

Transactions of the American electro-therapeutic association. (1899). Buffalo, NY: Author.

Verni, M. (1946). Modern beauty culture (2nd ed.). London: New Era Publishing.

Wagner, R. F., Brysk, H., & Tyring, S. K. (1997). Revisiting the Michel/Green controversy of 1879: Was Carron du Villards the first to use probe/needle electrolysis for permanent hair destruction? International Journal of Dermatology. 36. 947-951.

W. M. Meyer Co. (1936). The cosmetiste: A textbook on cosmetology with special reference to the employment of electricity in the care of the hair, scalp, face, and hands, also permanent waving and hair curling. Chicago, Ill: Author.

Woodbury, J. H. (1894). What dermatology has to do with beauty: How to remove all imperfections of the skin. New York: Fless & Ridge Printing Company.

Major Charles Eugene Michel [1833-1913] when he was serving in the Confederate army as a surgeon in the field. After the war he settled in St. Louis and set up his own opthalmology practice. He was also professor of ophthalmology at the Missouri Medical College from 1869 to 1907 (Missouri History Museum).

George Henry Fox [1846-1937], the first dermatologist to practice electrolysis with the hair in place.

1888 Mrs. Blake electrolysis treatments.

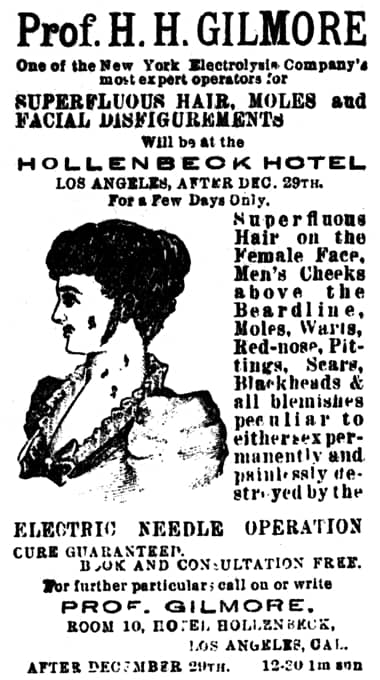

1894 Prof. H. H. Gilmore. Not all early lay practitioners were women. Prof. Gilmore appears to be travelling the country offering electrolysis services out of hotel rooms.

1903 Using electrolysis to remove superfluous hair in a Marinello salon. Note the positive electrode being held by the client.

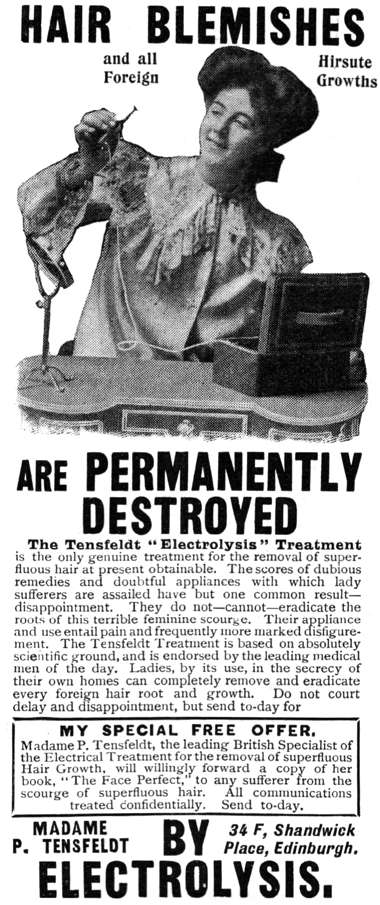

1906 The Tensfedt “Electrolysis” Treatment. An early home treatment machine.

1909 Part A: McIntosh electrolysis kit with battery, cords, electrodes and instruction booklet for use by an American barber (Moler, 1909).

1909 Part B: Drawing demonstrating electrolysis in operation in an American barber shop (Moler, 1909).

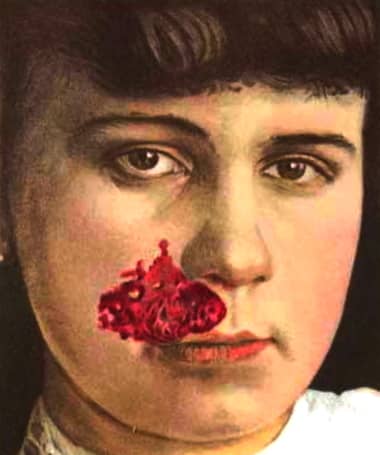

Electrolysis was not without risk. This 18-year old patient was treated in 1907 for a ‘naevus with cicatrices following electrolysis’ (Mould, Robison & Van Tiggelen, 2010).

1914 Electrolysis treatment.

1915 Zenobia Sisters advertising antiseptic electrolysis treatments. The local anaesthetic they used was probably cocaine.

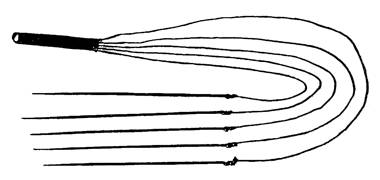

1916 Kromayer’s needles. These were first reported in 1908.

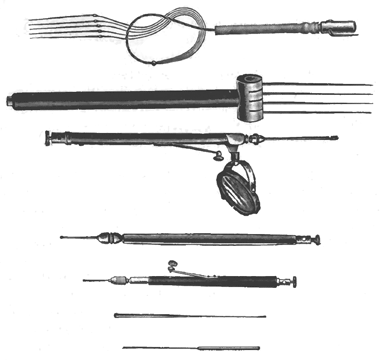

1919 A range of needles used in electrolysis. Not all of these would have been used in hair removal. Other facial blemishes such as moles, warts, spider veins, birthmarks, pimples, blackheads and acne were also treated using electrolysis. The size, shape and material composition of the needle were important considerations in the electrolysis treatment.

1924 Electrolysis procedure on eyebrow hair.

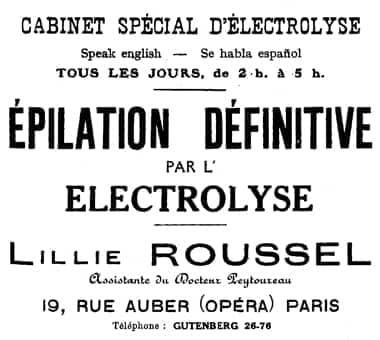

1928 Lillie Roussel (Assistant to Dr. Peytoureau).

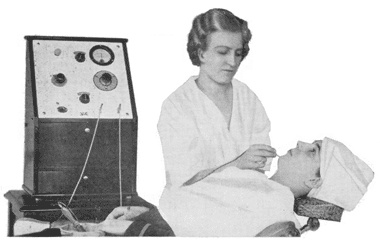

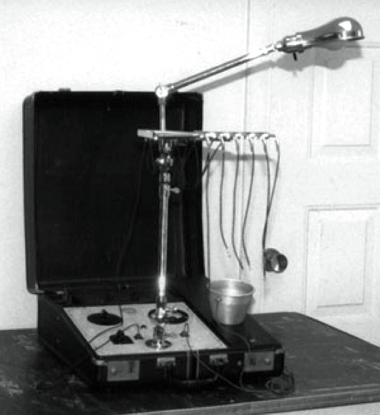

1936 Single needle electrolysis machine in operation. The machine in use is an improvement on earlier models. It has a dial to control current flow and an ammeter to measure it. The client has her hand in a bowl to complete the circuit (W. M. Meyer, 1936).

1936 Multiple needle electrolysis machine with an ammeter and a step rheostat to alter current flow as additional needles are added. The client has her hand in a bowl of water to complete the circuit (W. M. Meyer, 1936).

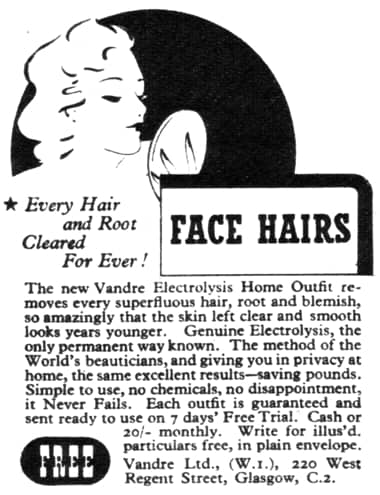

1935 Vandré Home Electrolysis Outfit.

1946 Illustration of the removal of a mole or wart through electrolysis (Verni, 1946).

A Kree multiple-needle electrolysis machine similar to the one patented in 1918. Paul Kree is often credited with inventing the multiple-needle technique in 1916, but the German dermatologist Ernst Kromayer had been using multiple needles since 1908, almost a decade earlier.

1946 Multiple-needle electrolysis treatment using a Kree machine.

A home electrolysis outfit produced in Australia, possibly from the 1940s. The kit consists of a 9 Volt battery, a clip to be attached to the ear to close the circuit and a pen with retractable needle to be inserted in a hair follicle. Directions for use:

“To use the Home Electrolysis Outfit. Connect the Red terminal to the battery marked + and the black terminal to either No. 6 or 9. Attach the clip to the lobe of the ear, then insert the needle into the exact root of the hair. A light tingling will be felt. Leave there for about 8 seconds, then the hair should be easily removed with tweezers. After using, dip the needle in a little Vaseline and remove the red terminal from the battery. A little zinc ointment applied to the face before and after operating is recommended. To test battery touch the clip and the needle to the tongue and if nothing is felt the battery is dead. Refills are obtainable anywhere. Do not allow the clip and the needle to touch each other or the battery will run down.”

1952 Vandre Electrolysis home Outfit.

Multiple-needle electrolysis treatment (Herzig, 2008).

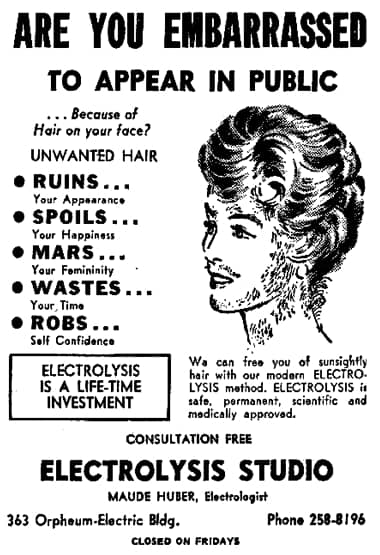

1968 Maude Huber Electrolysis Studio.