Face Skinning

In the nineteenth century, little could be done for individuals who suffered from pot-marks and other facial disfigurements. Marks, scars and blotches came in many forms, including pigmentation irregularities associated with melasma/chloasma, and the visible pitting produced by acne, smallpox or syphilis. Numerous remedies were published on the subject and newspapers of the time were full of advertisements for dubious products promising cures.

Dermatology and chemical peels

Dermatology was an established medical field by the nineteenth century, although more involved with syphilis and other venereal diseases than it is today. To help clients with severe skin problems some dermatologist experimented with chemical peels, using previously known agents as well as novel compounds produced by the developing petrochemical industry. Tinctures of iodine and lead, lime compresses and chemicals such as salicylic acid, resorcinol, phenol, croton oil and trichloroacetic acid were all explored as peeling agents. The German dermatologists Ferdinand von Hebra and Paul Gerson Unna were innovators in this area. However, like other dermatologists of the time, they only used peels to treat pigmentation and scarring problems; they did not regard ageing and wrinkles as signs of disease and therefore worthy of treatment.

Ecorchement

Although Ferdinand von Hebra and Paul Unna may have been unwilling to use face peeling for strictly cosmetic reasons, some French doctors were reputedly not so reticent. Face peeling was apparently a speciality of the St. Louis Hospital, Paris, where cosmetic improvements were considered to be of equal importance to disease (Covey, 1916, p. 254). The peeling procedure was referred to as ‘ecorchement’ which is literally French for ‘skinning’ – both terms that would disappear during the twentieth century to be replaced by the less drastic sounding term ‘peeling’.

Covey suggests that it was from Paris that the practice of ecorchement spread to the United States.

Some speculative “Yankee physician” managed to secure the process, and brought it to this country, where he disposed of it, in several cities, to beauty specialists for several thousand dollars. It is estimated that in one year he made over thirty thousand dollars by the sale of these formulas in different cities. The French gave it the name “Ecorchement,” but on this side of the water it is often referred to as the rejuvenating treatment, derma vita, desqua dermia and other coined names, bearing upon new life to the skin, and is the banner treatment in all beauty culture establishments.

(Covey, 1916, p. 254)

Covey also supplies a copy of the ‘original formula’ and the method of treatment.

Formula No. 1

Resorcine 80 parts Zinc oxide 20 parts Salicylic acid 4 parts Lard 40 parts Olive oil 16 parts Formula No. 2

White gelatine 8 oz. Zinc oxide 4 dr. Glycerine ½ dr. Boiling water q.s. Great care should be exercised in compounding these formulas, and better results will be obtained if they are prepared fresh each time they are used, and do not attempt to substitute vaseline for lard, in the first formula, unless you wish to meet with failure.

The first formula is applied to the face twice a day, for about four or five days, until the skin becomes brown, dry and commences to crack. Then the face is thoroughly washed with soap and water, to remove every particle of ointment, and after thoroughly drying the skin, the second application is used.

The ingredients of formula No. 2 are placed in a water bath, by first adding sufficient boiling water to dissolve the gelatine; then thoroughly stir in the other ingredients. This should be applied to the face with a small paint brush, and as you cover a surface, a piece of absorbent gauze, the size of the painted surface, should be immediately applied, while the gelatine is still hot; this adheres firmly to the skin, after the entire surface has been thoroughly covered. The same process should be repeated again, until you have several thicknesses of the gelatine and gauze, and a solid mask is formed.

At the end of three or four days, it will be noticed that this mask is breaking loose from the edges, and as soon as the mask becomes loose, it can be removed, and the face will be found very much the same color as a newly born baby, and is often very sensitive to the touch and air. The face is dressed with any good cold cream, and in a few days, the shade of the skin resumes its normal color, only we have an absolutely new skin, which in many instances, is marvelously beautiful, for the treatment has removed every mark or discoloration, which the old skin had accumulated in past years, and is properly named “the rejuvenating treatment,” as it will add the youthful appearance to any face.(Covey, 1916, pp. 251-257)

Ruth Maurer – the founder of Marinello who published material under the name of Emily Lloyd – describes another version of an ecorchement treatment.

The ecorchement system is a popular and effective method in removing the cuticle and thus refining the skin. Many people profess to believe that this process is a remedy for all the ills of the skin. Properly used, however, it is better after other treatments have been given for some time. As this particular form of treatment is not at all dangerous nor painful to the subject, it naturally has received a great deal of attention as well as commendation and may be recommended for the following troubles:—for refining the skin after a severe case of blackheads and pimples, for whitening and removing most of the wrinkles in ordinary skins, for making the skin wonderfully better in cases of obstinate chloasma, in fact, practically removing every vestige of this trouble and finally of most remarkable benefit in the treatment of eczema for which indeed it is almost a specific.

The process is performed as follows:—Each day for from five to seven days, a searching, antiseptic ointment is rubbed onto the skin and forced in with the blue light. The applications are made with cotton to prevent staining the finger-tips of the operator. After a few days the skin begins to assume a parchment-like appearance and becomes dry and leathery. As soon as this appearance is uniform, a number of coats of a liquid preparation must be painted on and allowed to dry until it forms a complete mask. After a number of days this mask begins to crack and then the old skin and the mask may be peeled off … leaving a perfectly formed new skin beneath. Neither the peeling process nor the application of the ointment nor the wearing of the mask will be found at all painful, but the results will certainly be all that one could desire. Hence, as the only disagreeable feature is the enforced seclusion for a matter of a week or ten days, the process does not possess many terrors for the truly ambitious soul who is determined to look her best.(Lloyd, 1907, p. 92)

Unfortunately Maurer makes no mention of the chemicals used in this treatment. It is also worth noting that she did not include ecorchement in her Marinello textbooks published from 1915; perhaps she considered it too dangerous for most beauticians.

See also: Marinello

Electro-ecorchement

As with many other skin treatments of the time electricity was often included as part of the treatment. Thanks to Harriet Hubbard Ayer we have a good description of an electro-ecorchement process.

The patient who is to be skinned takes board for a week or two or three with the professional skinner. Then she pays for her board and torture in advance. She pays from $300 to $500, which is honestly not too high. A prohibitive price is, on occasions, a virtue. Next the skinnee takes a seat in the big operating chair, and the skinner, after bathing her client’s face in a solution, we shall say, of salicylic acid—and other acids would be just as affective—wets a sponge attached to an electrode, with the same solution, which is in turn attached to an electric battery and, turning the current on, passes this sponge over the skinnee’s countenance.

The application of an irritant powerful enough to produce an inflammation as that which follows this first treatment savours rather of the inquisition of our late friends, the Spaniards, but no one is obliged to undertake it. …

Days and nights of agony of a large and generous kind are now liberally bestowed upon the subject who is wrestling so valiantly with Time. Anodynes are given to make the pain endurable. For active suppuration must ensure before the plasters can be removed, before the three skins that are to come away can be literally eaten off, and this part of the performance is not jest.

The suppuration of the whole face requires about a week’s time, and is truly wonderful and awe inspiring. During this time the skinnee subsists on liquids taken through a glass tube. She cannot speak or open her mouth, which is perhaps a qualified blessing.

When the suppuration ceases, the plaster begins to loosen. It comes only in bits, bringing with it the destroyed cuticle, which looks like old parchment.

The “patient” now shows a face just about the color of a newborn infant’s—just as red and without a line. Three months later the redness has disappeared, and a skin of delicate texture, white and transparent, is the result.

There is no question as to the improvement in appearance, if one consider the face of a woman of sixty devoid of every trace of a line of thought or experience an improvement upon the countenance that tell of self-sacrifice, patience, and courage.(Harriet Hubbard Ayer, 1902)

Phenol-croton oil peels

Although carbolic acid was a favoured chemical for skin peels, by the 1920s, croton oil-phenol formulas were also being used in the United States. It was believed that phenol was the active ingredient in the formula but Hetter (2000) suggests that croton oil was the vital element and that phenol was only the carrier in the solution. We do not know the precise technique used by everyone but Hetter’s study in this area has revealed much. The process used appears to have been as follows:

- First the croton-oil-phenol solution is applied and then covered with adhesive plaster.

- Within 3 days the paster falls off and thymol iodine powder is then dusted on the skin to form a crust.

- The crust comes off in 5 more days and then salves are applied.

Hetter also identified the main U.S. practitioners:

- Jean DeDesley: 1920s–1950s

- Antoinette LaGrassé: 1920s–1950s

- Verner Kelsen: 1940s–1980s

- Cora Galenti: 1940s–1980s

- Arthur Gradé: 1940s–1990s

- Maryanne Coopersmith: 1950s–1970s

- Miriam Maschek: 1950s–1970s

- Jacqueline Stallone: 1970s–1980s

- Jacque Thomas: 1970s–1990s

- Christy Warren: 1970s–1990s

These practitioners did not develop their technique independently of each other but passed the secret from one person to another – who came up with the original formula is unknown. Given its lucrative nature, there was a good reason to keep the treatment a secret. It was particularly popular after the 1920s with middle-aged actresses in the Hollywood movie industry (Blum, 2003 p. 209) and with financially ‘well-heeled’ older residents of Miami.

In the 1960s, some American dermatologists gained access the phenol-croton formulas used by the lay peelers and this resulted in the publication of the Baker-Gordon formula in 1962. A modified version of Baker-Gordon formula is still in use today.

Baker-Gordon’s Formula [modified]

Components % p/p Phenol at 88% 3 Demineralized water 2 Croton Oil 3 Liquid soap 8 (Velasco et al., 2004)

Concerns about face peeling

Published concerns about face peeling appeared intermittely through the early twentieth century, as this 1936 report from Paris suggests:

There is no doubt that the beauty treatment known as Peeling has been very widely practiced here of late. Many women who have had the courage and the necessary time at their disposal to place themselves in the hands of those “doctors” who undertake to provide their clients with a new skin sing the praises of these specialists after they have gone through the ordeal. True they have undergone suffering through the use of moderately caustic solutions with which their faces have been painted here and there. For fully a week they have been kept indoors, prisoners, as it were, in their boudoirs; and their friends who were not “in the know” have wondered what has become of them. Day after day they have anxiously examined their faces in the mirror, and certainly at first they have almost regretted their faith in the peeling method. How their faces burned and itched!—and what a sight they presented when the old skin began to come off! Some of them, it appears, have been so foolish as to try to hasten the process by pulling off the old skin, with the result that painful irritation has set in. Then an appeal has been made to their “doctors,” who very rightly scolded them for their impatience. However, they assure me that in the end all was well: their wrinkles and the pockets under the eyes had disappeared as though by magic, and a new epidermis—a babe-like skin—was theirs. Their friends marvel at the transformation which has taken place, and some, not being able to account for the long absence from well-known meeting places, suspect that holiday-making accounts for it. “A gentleman of a certain age, and one who is not given to compliments,” said one of the ladies who have recently been “peeled” to me, “could not resist going into ecstatics regarding my new complexion when he met me the other day. He could not make it out. Naturally I had to tell him a white lie—namely, that the French climate (I‘m a Colonial, you know) suited me down to the ground, and that whenever I came on a visit to Paris I grew more and more beautiful.”

But what about the other side of the picture? Parisian women are not all agreed as to the advisability of “peeling.” In fact, there is a controversy raging. It is alleged that there have been minor “accidents”; some say quite serious ones, and the Doctors of Faculty of Medicine are issuing warnings.(The Hairdresser and Beauty Trade, 1936)

Medicalisation

Once face peeling became an established medical practice the profession put pressure on the authorities to close the lay peelers down. The medicalisation of this area was not without its benefits. Medical science was better placed to examine the process of chemical peeling and the chemicals involved;, it produced more effective formulations and deeper chemical peels than those used by the lay peelers and was able to combine chemical peels with other cosmetic procedures including dermabrasion and laser resurfacing.

Updated: 25th January 2019

Sources

Ayer, H. H. (1902). Harriet Hubbard Ayer’s book of health and beauty. New York: King-Richardson.

Blum, V. (2003). Flesh wounds: The culture of cosmetic surgery. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cooley, A. J. (1866). The toilet and cosmetic arts in ancient and modern times with a review of the different theories of beauty and copious allied information social, hygienic, medical. New York: Burt Franklin.

Covey, A.D. (1916). The secrets of specialists. Incorporating profitable office specialities (5th ed.). Chicago, Ill: The Adams Publishing company.

The hairdresser and beauty trade (1936). 7(4). 19. London.

Hetter G. P. (2000). An examination of the phenol-croton oil peel: Part II. The lay peelers and their croton oil formulas. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 105. 240-248.

Kay, G. (2005). Dying to be beautiful: The fight for safe cosmetics. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press.

Lloyd, E. (1907). The skin. Its care and treatment (3rd. ed.). Chicago: McIntosh Battery and Optical Company.

Velasco, M. V. R., Ribeiro, M. E., Bedin, V., Okubo, F. R., & Steiner D. (2004). Facial skin rejuvenation by chemical peeling: Focus on phenol peeling. Brazilian Annals of Dermatology. 79(1), 91-99.

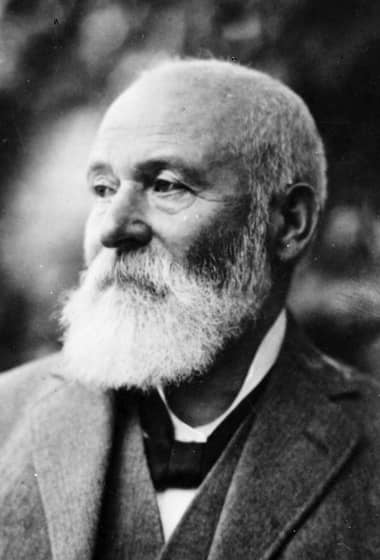

Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra [1816-1880] the Viennese dermatologist who was a nineteeth century innovator in the use of chemical peels.

Paul Gerson Unna [1850-1929]. He worked with Ferdinand von Hebra and in 1882 described the use of salicylic acid, resorcin, phenol and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) in chemical peels.

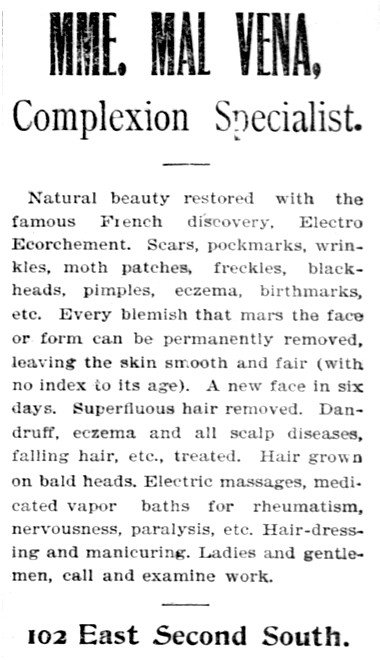

1898 Complexion Specialist, Madame Mal Vena advertising electro-ecorchment treatments.

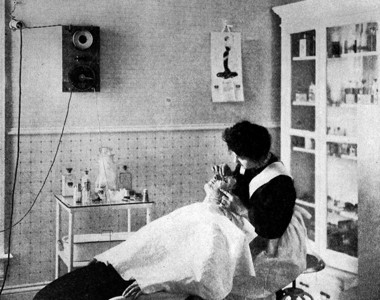

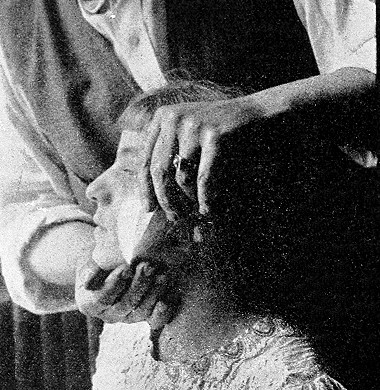

1907 Removing marks and old cuticle in a bad case of chloasma after an ecorchment treatment in a Marinello salon.

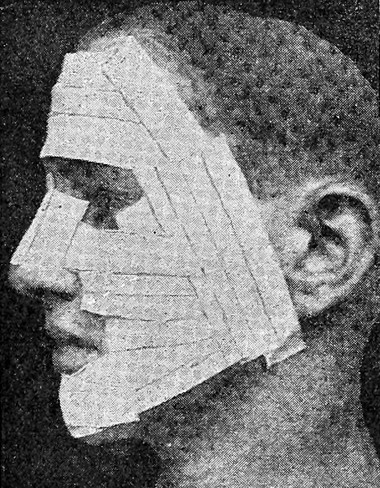

Bandaging during a carbolic acid ecorchement treatment. “Another still more heroic measure of destroying the outer skin is to apply pure Carbolic Acid; this treatment is used with a small brush, on the surface of the skin, and allowed to penetrate the integument, when a second or third coat is given. After the skin has become dry, the entire surface is covered with adhesive strips; this is allowed to remain for three or four days, until the outer skin sloughs, and suppuration takes place. The skin is allowed to remain, however, until nature desquamates the integument. This treatment is frequently resorted to in deep-seated smallpox pittings, and the most favorable reports have been obtained in many cases” (Covey, 1916).

Scabbing typical of a deep face peel. “The old skin forms a dense scab, which can be removed in a few days, leaving a beautiful, new, pink under skin. This process of scabbing is absolutely necessary to obtain the best results, but the face has a horrible appearance of one continuous scab and unless the patient is advised beforehand, she will think her face is ruined; it is, therefore, often advisable not to allow the patient to see her face until the treatment is completed. I, therefore, keep the face mask in continuous use, until the last remnant of old skin is removed” (Covey, 1916).

Peeling the skin during an ecorchement treatment (Covey, 1916).

Peeling the side of a face to remove a blemish during an ecorchement treatment (Covey, 1916).

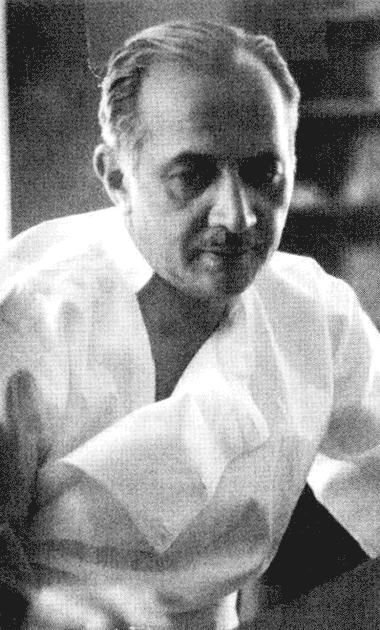

Dr. Adolph Brown, the first plastic surgeon to to use a phenol croton-oil peel using a formula he probably obtained from the lay peeler Arthur Gradé.

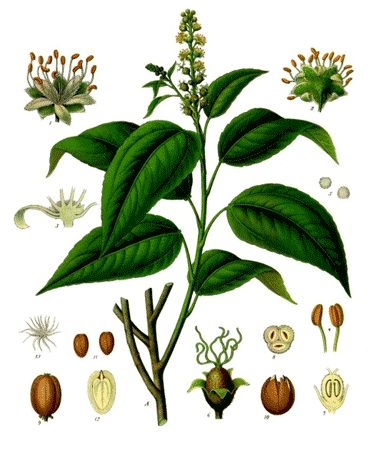

Croton tiglium. “Croton oil is a fixed oil extracted from the seed of the Croton tiglium plant. In the [Baker-Gordon] formula, it is a component that raises the capacity of phenol to coagulate the skin’s keratin, as it acts as a promoter of cutaneous penetration in elevating the site’s vascularization. It is considered to be a resin, and its bioactivity is due to free hydroxyl groups. Highly toxic for the skin, croton oil causes edema and erythema. It is insoluble in water and highly soluble in alcohol and benzene (phenol is a mono-hydroxybenzene)” (Velasco et al., 2004).