Lina Cavalieri

Lina Cavalieri was born on the 25th December, 1874 in Viterbo, Italy – the oldest of three children – her birth name Natalina coming from the Italian word ‘natale’ for Christmas.

Accounts of Cavalieri’s early life are generally unreliable but the consensus is that the family was impoverished so Lina was put to work at an early age and, after a series of other jobs, began earning money as a street singer. When combined with her natural beauty and a talent for performance, her voice led to stage performances, a short career as an opera singer on both sides of the Atlantic [1900-1916], and then work as an actress in a series of movies for various American and European film studios [1914-1920]. Along the way she attracted the attentions of a succession of men, some of whom – as noted by her contemporary, the New Zealand born opera singer Frances Alda [1879-1952] – played a role in furthering her career.

Cavalieri’s extraordinary beauty evoked all manner of legends.

It was generally accepted as truth that she had begun her career as a flower-seller in Rome. There an elderly marquis had seen her and discerned under her peasant dress a beauty that the whole world was to acclaim. Like Shaw’s Galatea, Lina repaid washing and feeding. The Marquis’s generosity ran, I believe, to an apartment and lessons in singing and dancing.

The last took Lina to Ronacher’s in Vienna, and out of reach of the Marquis. Success in Vienna sent her to Paris and the Folies Bergères, where she was billed as ‘The Most Beautiful Woman in Paris.’

When I went to Paris to study with Madame Marchesi, Cavalieri was all the rage. She was famous for her beauty, her jewels, and her lovers. She had already started her career in Grand Opera by singing Nedda, in Pagliacci, in Lisbon. She was not a success in it, however; though later, in Paris, she sang Fedora with Caruso. I remember going to the first performances thinking she would be laughable, instead of which I was impressed by her singing and acting. And she was unbelievably beautiful.(Alda, 1937, pp. 131-132)

Beauty Culture

Frequently described as the ‘world’s most beautiful woman’, or ‘Venus on earth’, Cavalieri capitalised on her beauty and notoriety in a number of ways that give her a place in the history of Beauty Culture.

First, between 1909 and 1914, she put her name to hundreds of beauty articles published in American newspapers under the general heading ‘My Secrets of Beauty’. I doubt they were written solely or largely by her.

MME. LINA CAVALIERI the famous beauty and the well-known grand opera soprano, who has made a life-long study of beauty culture, and has, indeed, herself worked out many recipes whose secrets are her own, has arranged to write for this newspaper a series of extremely interesting and valuable articles on the Secrets of Beauty.

(New York Herald, 1909)

The articles covered a wide range of topics and were later complied into a book of the same name, published in 1914. A number of similar beauty articles listed as hers also appeared in the Parisian magazine Femina.

Second, like other opera and movie stars, Cavalieri also did endorsements, although not as many as might be thought given her fame. It is possible that the scandals surrounding her relationships with men, particularly her second, brief marriage in 1910 to Robert Winthrop Chanler [1872-1930] – a member of the influential Astor family – may have been a limiting factor.

Above: Lina Cavalieri endorsement for Séduction perfume sold by Gellé Frères, a French perfume and soap company founded in 1826.

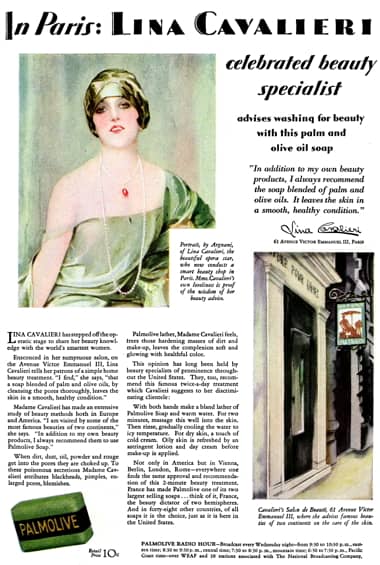

Her most lucrative endorsement was probably for Palmolive Soap which began in 1929 and continued through the 1930s.

Third, Cavalieri also used her reputation as a great beauty to establish beauty businesses. In 1909, she opened a shop at 240 Fifth Avenue, New York to sell perfumes, powders and other cosmetics. Possibly set up to provide work for her brother Oreste, it does not appear to have lasted very long.

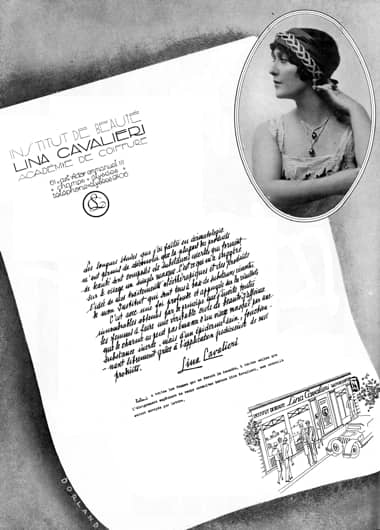

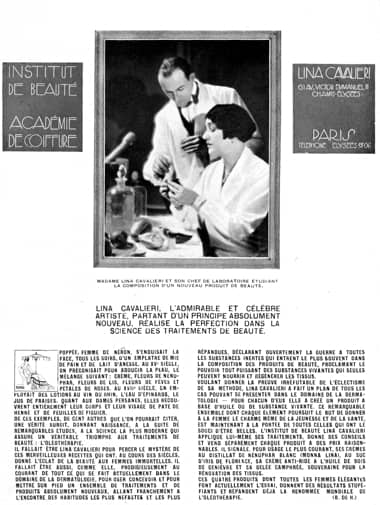

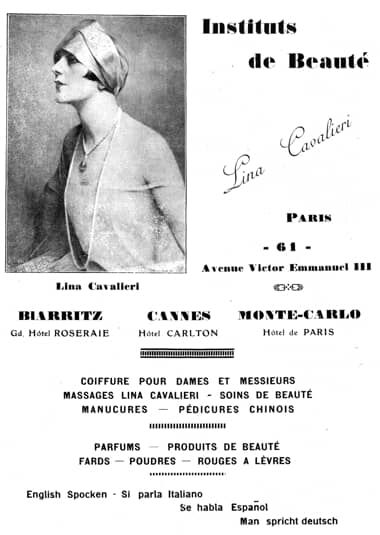

A more successful venture was the Lina Cavalieri Institut de Beauté and Académie de Coiffure that opened in Paris on the Avenue Victor Emanuel III in 1926.

Above: c.1928 Lina Cavalieri Institut de Beauté and Académie de Coiffure at 61 Avenue Victor Emanuel III, Champs Élysées, Paris with window displays of perfumes and other beauty products. Italy sided with Germany during the Second World War so the street was renamed Avenue Franklin D. Roosevelt after his death in 1945.

Above: c.1928 Cubicles in the Institut de Beauté.

Branches of the Paris business were also opened at the Hôtel Carlton in Cannes, the Grand Hôtel Roseraie in Biarritz and the Hôtel de Paris in Monte Carlo. By 1931, Cavalieri also had an establishment in the French summer resort of Le Touquet.

Although Cavalieri and her third husband Lucien Muratore were photographed as actively involved in the business it is hard to know how engaged they were and it is possible that she was simply paid for her name. Cavalieri divorced Muratore in 1927 so presumably his part, if any, in the enterprise must have been short lived. If Cavalieri had a stake in the business I suspect that she left most of the day-to-day operations to others such as Monsieur Ficklinger the salon director in 1932.

Salon treatments

Information on the beauty treatments offered at Cavalieri’s Institut de Beauté is fragmentary at best. From advertising we know that the salon provided hairdressing for men and women, massage and other beauty treatments as well as manicures and pedicures.

I have found no evidence that she offered electrolysis which would be unusual.

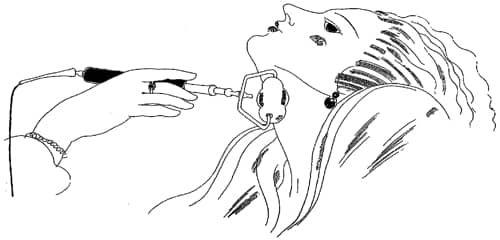

Above: c.1928 Client undergoing a facial treatment.

Also surprisingly, Cavalieri appears to have been against using high-frequency currents in facial treatments, restricting their use to the scalp.

Above: 1927 High-frequency treatment using the rake electrode to stimulate the circulation of the scalp.

See also: High Frequency

Massage

If her book is to be believed, Cavalieri placed a great deal of faith in Swedish massage. Like others of her time she held the view that massage could build up or reduced body tissue depending on how it was practiced.

Give me an excellent masseuse and I could dispense with a doctor, except in some tremendous emergency. Thin shoulders can be plumped and fat shoulders can be reduced by massage. If they are thin a light massage, using a rotary movement of the palms of the hands, applying olive oil copiously, will gradually plumpen them. If they are fat the massage should be much deeper and more vigorous. The masseuse should knead as near the bone as possible.

(Cavalieri, 1914, p. 67)

See also: Massage Wrinkles and Double Chins

As well as Swedish massage on the body, Cavalieri also considered gentle massage to be an important preventative in the fight against age lines on the face.

For half my life I have had my face massaged frequently, and for many years I have had it massaged every day. With what result? That my face is absolutely free from lines. That my complexion is smooth and absolutely free from blemishes.

(Cavalieri, 1914, p. 74)

Masque de Beauté

Cavalieri also placed great store in the rejuvenating power of electricity and it played a role in a number of her therapeutic practices.

Above: c.1928 Therapists getting instructions on using a roller electrode.

The signature electrical treatment of the salon appears to have been the Masque de Beauté which was used in facial routines designed to firm the throat, sharpen the jaw and reduce facial lines.

Study the drooping cheek muscles and you will notice that they are apt to sag from the cheek over the edge of the lower jawbone, and try to melt in an ungraceful way into the neck. This is not to be permitted. The jawbone should keep its thin, fine edge to the end of life. The nearer it is like a razor edge in sharpness the nearer you are to keeping the facial line of youth.

(Cavalieri, 1914, p. 249)

These treatments began by positioning the client, dressed in a kimono, on a comfortable chaise-longue. After being given a bar electrode to hold to complete the circuit, an electric roller was then used to firm the throat. This was followed by a session with a ball electrode to reduce any ‘smile lines’ in the naso-labial fold and expression lines between the eyebrows.

Above: 1927 Throat roller.

The ball electrode was then covered with a chamois and used around the eye area to reduce any signs of ‘crow’s feet’.

Above: 1927 Eye treatment.

The Masque de Beauté – a device made up of a chinstrap with two long pads of leather to support the throat and chin along with two small ropes that ran from the lips to the nostrils – was then positioned over the face after it was treated with an astringent.

Above: 1927 Masque de Beauté.

The electrical current was turned on and the client was left to relax for 20 minutes while the Masque de Beauté did its work. After the mask was removed the client’s cheeks, lips, chin and forehead were then rubbed with ice to help close the pores.

I can only guess the role that electricity played in these treatments. The ball and roller electrodes and the mask may have all been employed to ‘intensify’ the effect of the astringent but they may have also been used to contract and tone the facial muscles.

Also see: Galvanic Treatments, Faradic Treatments and Straps, Bandages and Tapes.

Steaming

The only other Cavalieri salon treatment that I know of combined steam generated from rose water with exposure to purple/blue light, another common treatment of the time.

Above: Facial steamer as used in the Cavalieri salon. The device appears to be a Vapofor.

See also: Vaporisers (Steamers & Atomisers) and Red Light, Blue Light

Products

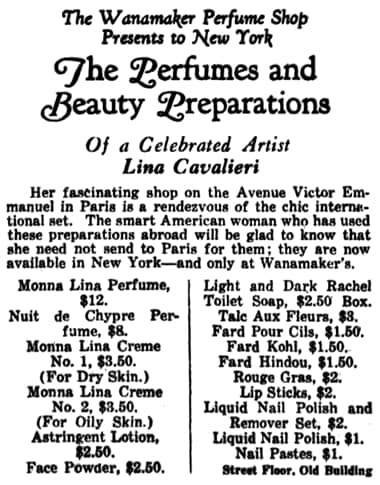

Lina Cavalieri cosmetics were sold through the various salons that operated in her name but were also available from some other French outlets, such as the Parfums d’Isabey shop at 20 Rue de la Paix, Paris, and were retailed across the Atlantic in a few American department stores such as Wanamakers in New York.

Above: Publicity photograph of Cavalieri supposedly instructing a cosmetic chemist on how to formulate one of her cosmetics while an assistant takes notes of the formulation.

Skin-care

Cavalieri followed the French tradition and named most of her skin-care cosmetics by number. American advertising suggest that Monna Lina was the main fragrance used to scent them. Monna Lina – a ‘tribute’ to the Mona Lisa (La Gioconda), painted by Leonardo da Vinci [1452-1519] – and Cavalieri’s cheaper Nuit de Chypre were created by Parfums d’Isabey, founded in 1924, in Paris, as the Sociéte Parisienne d’Essences Rares et de Parfums.

Above: c.1928 Lina Cavalieri perfume – probably Monna Lina, a scent created by Julien Viard of Isabey that was packaged in a casket by the cardboard manufacturer Sennett – and a skin cream housed in a deluxe jar.

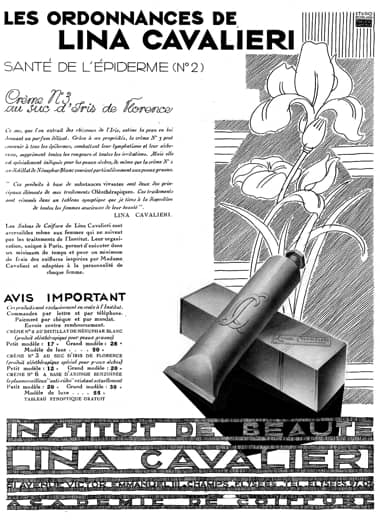

Cavalieri’s skin-care creams were described as being used in Oléothérapie (Oil therapy). Essentially this meant using certain oils and herbs – supposedly employed by ancient Greek and Roman women – to create products based on ‘wonderful recipes from antiquity’ that were reformulated using modern techniques. These could penetrate the pores, facilitate ’skin breathing’, remove toxins and provide nourishment, all common themes of the time.

See also: Skin Breathing and Skin foods

Four of her skin-care products received special attention: Crème No. 2 for dry skin, containing a distillate of white water lilies; Crème No. 3 for oily skin, made with essence of Florentine irises; Crème No. 6, an anti-wrinkle skin food made with juniper berry extract; and Gelée Camphrée No. 5, a camphorated jelly also used as a skin regenerator.

Above: c.1928 Lina Cavalieri Bath Salts, Crème No. 6 (in two sizes) and Talc aux Fleurs, a dusting powder.

The only other skin-care product that I am aware of was Lotion Onctueuse No. 7 which may have been an astringent.

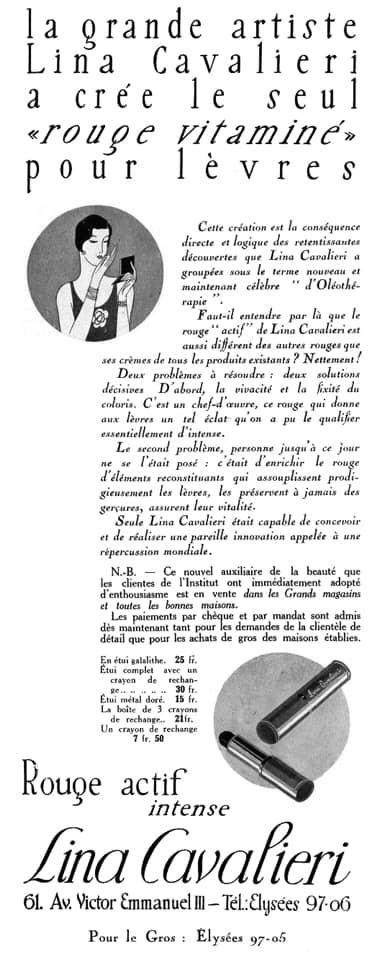

Make-up

Cavalieri developed a fairly comprehensive make-up range that included face powders, rouge, lipsticks and nail polish. One advertisement suggests that her face powders came in twenty-six shades but the shade names have eluded me.

She also sold eye make-up including Fard pour Cils, Fard Kohl and Fard Hindou. I have been unable to determine exactly how these were differentiated but it appears that her Fard Kohl and Fard Hindou were mascaras of different colours: Fard Kohl being black while Fard Hindou was sepia/brown.

Closure

The French business survived Cavalieri’s divorce to Muratore in 1927 but was abandoned sometime in the second half of the 1930s and gazetted as wound up in 1938.

Above: 1932 The salon was robbed at gunpoint and this may have deterred new clients. Note the change in signage from ‘Coiffure pour Dames’ to ‘Siege (Siège) Central’.

By the time the Paris business had closed its doors for good, Cavalieri was living in Florence, Italy. Sadly, in 1944, she was killed during an Allied air raid on the city.

Timeline

| 1909 | Perfume and cosmetic shop opened at 240 Fifth avenue, New York. |

| 1926 | Paris salon opened at 61 Avenue Victor Emanuel III. |

| n.d. | Paris salon closed. |

| 1938 | French business liquidated. |

Updated: 24th January 2020

Sources

Alda, F. (1937). Men, women and tenors. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Armstrong, A. (1908). Lina Cavalieri, the famous beauty of the operatic stage. Munsey’s Magazine, 39(1), April, 77- 78.

Cavalieri, L. (1914). My secrets of beauty. New York: The Syndication Syndicate, Inc.

Cavalieri, L. (1927). L’art de s’embellir. Femina, February, 11-15.

Fryer, P. & Usova, O. (2004). Lina Cavalieri: The life of opera’s greatest beauty, from 1874 to 1944. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. Inc.

Lina Cavalieri [1874-1944].

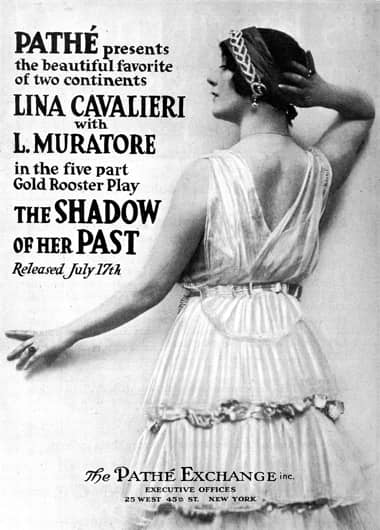

1916 Trade advertisement for film ‘The Shadow of her Past’, made and released in Italy in 1915 as ‘Sposa nella morte!’. Her striking looks and well-known relationships with numerous suiters – including her 1910 scandalous, brief marriage to Robert Winthrop Chanler [1872-1930], a member of the Astor family – meant that Cavalieri was usually typecast as a vamp.

1919 Lina Cavalieri and her third husband, the operatic tenor and film actor, Lucien Muratore [1876-1954]. Photographs of the pair had to be staged as she was taller.

1926 Lina Cavalieri Institut de Beauté and Académie de Coiffure.

c.1928 Clients entering the Lina Cavalieri Institut de Beauté and Académie de Coiffure. The plush interior was described as handsomely decorated in green and gold with tinted ivory trim, yellow silk curtains and greyish-yellow velvet cushions interspersed with antique prints and porcelain vases.

1926 Lina Cavalieri. This advertisement list the salon address as 65 Avenue Victor Emanuel III but advertisements after 1926 use number 61.

c.1926 Lina Cavalieri viewing the construction of the Institut de Beauté.

c.1926 Lina Cavalieri supposedly formulating cosmetics for the salon.

c.1926 Lucien Muratore, listed as the Chief Executive Officer, at work in the Institut de Beauté.

1926 Lina Cavalieri Institut de Beauté.

1926 Lina Cavalieri Oléothérapie.

c.1926 Salon manicure treatment. A chiropodist was also available for foot treatments.

c.1926 Salon treatment, possibly a Masque de Beauté.

1926 Lina Cavalieri products sold through Wanamakers, New York.

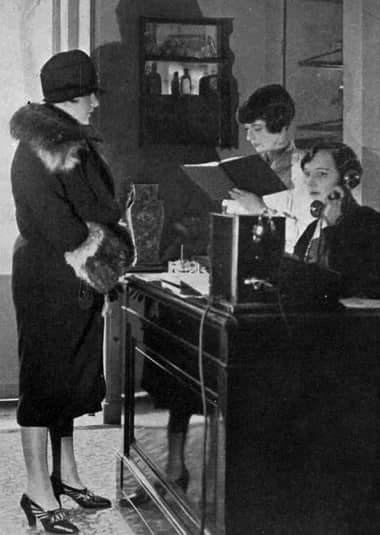

1927 Reception desk at the Lina Cavalieri Institut de Beauté.

1927 Lina Cavalieri Créme No. 2 au distillat de Nénuphar Blanc in a deluxe jar.

1927 Lina Cavalieri Créme No. 3 au suc d’Iris de Florence in tube form.

1927 Lina Cavalieri Rouge Vitaminé pour lèvres.

c.1928 Lina Cavalieri skin cream in a deluxe jar and a bottle of Monna Lina Eau de Cologne.

c.1928 Salon treatment, possibly a roller treatment for the throat.

1929 Lina Cavalieri Institut de Beauté. Cavalieri’s real image disappeared from advertisements fairly quickly after 1926, presumably because of her matronly image.

1929 Lina Cavalieri endorsement for Palmolive Soap. Some Palmolive advertisements of the 1930s used photographs of Cavalieri but they were heavily doctored to make her look younger and thinner.