Vaporisers (Steamers & Atomisers)

There were two main types of vaporisers that have been used in beauty salons over the past hundred years or so. One type, which I will refer to as steamers, generated and used the benefits of steam. The other, which I will call atomisers, relied primarily on the production of a fine spray of water. These devices, which were mainly used in facial treatments, were known by a variety of names including vaporisers, atomisers, steamers and pulverisers.

Steamers

The general principle behind a steamer is simple; boil water to produce steam and then direct this over the face. The practice was used in medicine well before it was taken up by Beauty Culture as, for example, in steam inhalers.

Above: A croup kettle. Devices like this were used in the nineteenth and twentieth century to treat children suffering from croup.

When used in medicine, inhalers of this type would often mix medicinal ingredients in with the water. However, as these medications would need to evaporate to mix with the steam only volatile medicinal ingredients would have any effect. In early Beauty Culture, tinctures were often added to the water but today, steaming generally uses water alone. Modern machine manufacturers generally recommend distilled or filtered water because tap water can leave calcium or other mineral deposits that may cause the steamer to malfunction after an extended period of use.

Many early steamers look similar to steam inhalers, but their use in Beauty Culture stems more from the nineteenth-century interest in steam bathing than anything else.

Russian baths

By the late nineteenth century, bathing, either in public baths or at home, was becoming more common in the middle classes. Along with the standard facilities offering a shower or a bath there were also Turkish baths, which involved a dry heat treatment, and Russian baths, which used steam.

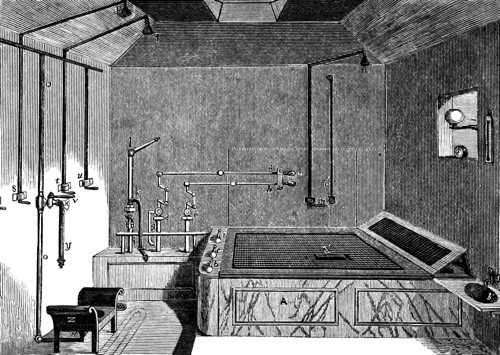

Above: 1885 Interior showing the facilities in a Russian bath house in Cavendish Square, London (Roth, 1885).

A Russian bath consisted of steaming, followed by massage and light flagellation, a wash with warm or cold water and a cold plunge to finish. Russian baths were recommended for the treatment of a wide range of afflictions ranging from asthma, constipation and joint pain, to smallpox and syphilis. It was also said to have beneficial effects on the skin.

We content ourselves with stating that the direct effect of the bath manifests itself in the skin and the mucous membranes of the respiratory organs; that it accelerates the circulation of the blood; reddens and softens the skin; produces a profuse perspiration during and after the bath; causes a slight and brief artificial fever, with increased activity of the skin and mucous membranes of the respiratory organs, by which the increased irritability of the arteries and the too great sensibility of the nerves are lessened.

(Roth, 1885, p. 25)

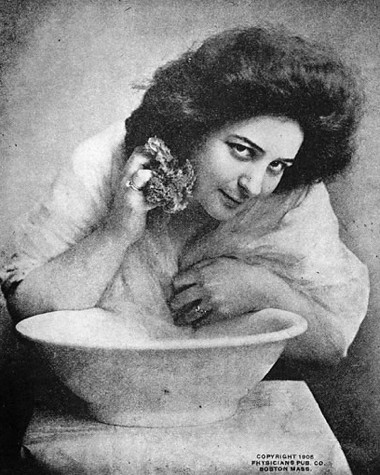

Bathing was also done in the home. However, as drawing, carrying, and heating large amounts of water was generally a very time consuming task, a lot of washing was done in basins using sponges or cloths. Steaming was also done in this manner with women placing their face over a bowl filled with very hot water. As with a Russian bath, steaming the face would generally be followed with friction and splashing with cold water.

There is nothing to be more highly recommended than giving the face, daily a good Russian bath, usually considered best just before retiring, as one is less liable to take cold then. For ten minutes or so, steam the face by holding it above a dish of boiling water; then bathe gently and freely, using the water as hot as you can bear, plunging the face immediately after into cold water. Wipe dry on a soft towel, being sure to wipe up, as this is said to be a means of preventing wrinkles. This bath is an excellent means of removing from the pores all foreign substances and rendering the flesh of the face beautifully soft, white and firm.

(Farbab, 1892, p. 9)

Although a basin of hot water would be adequate, a device specifically designed for this purpose – sometimes referred to as a Russian steamer – could also be purchased.

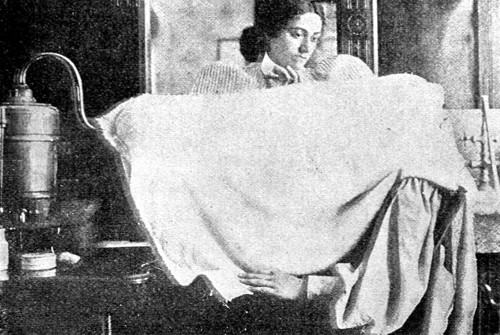

Above: 1903 Mrs. Pomeroy’s Russian Steamer.

Steaming the face in this manner was performed in many of the commercial beauty establishments that began to proliferate towards the end of the nineteenth century. Adherents of steaming, like Mrs. Pomeroy, believed that it helped cleanse the skin and make it supple, increased the amount of nourishing blood flowing to the face, and opened up the pores thereby reducing ‘congestion’.

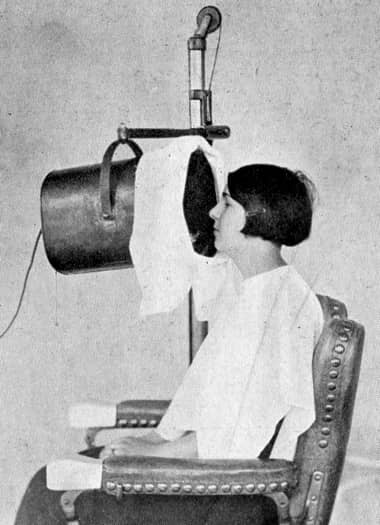

Above: 1911 Steaming treatment.

Detractors, like Eleanor Adair, said that it robbed the skin of nourishing oils and made the skin lax which induced wrinkles. Others took a more moderate position.

Face steaming is a method of treatment that may be highly beneficial or injurious, according as it is done. Too frequent applications of steam will cause wrinkles, by making the skin flabby, but an occasional bath of this kind serves the purpose of opening the pores to remove dust and helping to keep the skin supple and in good condition.

Special arrangements for this treatment may be bought, but they are expensive, and quite as good results may be secured from simple contrivances if they are made to hold the steam. A chafing dish answers the purpose admirably indeed, so will any receptacle in which water may be kept just below the boiling point. Any kind of vessel over an alcohol lamp, or gas if the jet be low and easily reached, can be adapted. It remains then to put over the flame a fairly large surface pan, or basin, with enough water to throw out a good volume of steam.

It is worth remembering, before going through this cleansing experience, that boiling steam will burn the skin, and so the temperature of the water must be a trifle lower than the boiling point, yet sufficiently high to throw out heat that will generate perspiration.

After everything is arranged for the bath the face should be well rubbed with cold cream, applying it thickly with the finger tips and rubbing vigorously in rotary motion over the entire face, making the upward part of the stroke stronger than the downward. This will take at least five minutes, and longer if properly done. The bath should then be ready, and the face bent over, holding a towel so the steam is thrown directly on the skin. If necessary to get fresh air to breathe, the mouth may be uncovered for about two seconds.

After the face is hot, and perspiration starts, it should be wiped with soft old linen to remove the grease, and then the face should be steamed again. This wiping is repeated until there is no trace of grease. Fifteen or twenty minutes should be devoted to the bath, and at the end of this period the face must be wiped for the last time. For the final treatment cold water may be dashed over to tighten the skin, and if there is no eruption an excellent lotion, made from a gill of alcohol and an ounce each of spirits of camphor and spirits of ammonia, two and a half ounces of sea salt, with enough boiling water to make a pint, may be applied to the flesh. This is not used until it is cold, and then the skin is soaked with it. It is an excellent tonic, and may be massaged into the neck, throat and arms, as well as the face.

Steaming by this method should not be resorted to oftener than once a week. Carefully done, it will soften and refine the skin and clear the complexion.(Mixter, 1910, pp. 87-88)

See also: Mrs. Pomeroy and Eleanor Adair

As the twentieth century progressed, the use of steaming became less controversial and the machines now are a common sight in modern beauty salons. The reasons for its inclusion are much the same as those given long ago. Steam supposedly helps to open up the pores, making it easier remove dirt, grease and make-up, and make extractions easier; softens the skin, thereby making exfoliation more effective; and increases blood circulation, which brings nutrients to the skin and removes wastes.

Enhancements

Beauty Culture ‘enhanced’ the basic stream treatment in two main ways, both of which were used mainly to treat clients suffering from facial skin eruptions.

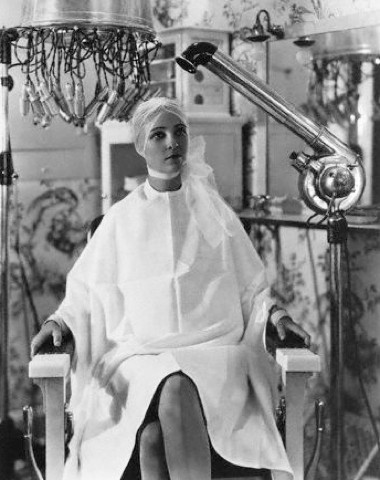

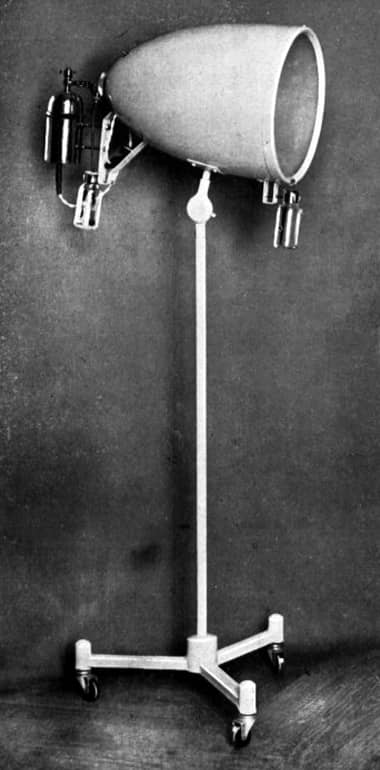

1. Blue light: An early development was to combine steaming with a blue light treatment. Blue light was believed to have an antiseptic and astringent action and, like steam, was used to treat pimples and acne.

Above: 1928 Bain de Vapor et de Lumiere “Vapofor” available from J. E. Canetti & Cie, 24 Rue de Paradis, Paris.

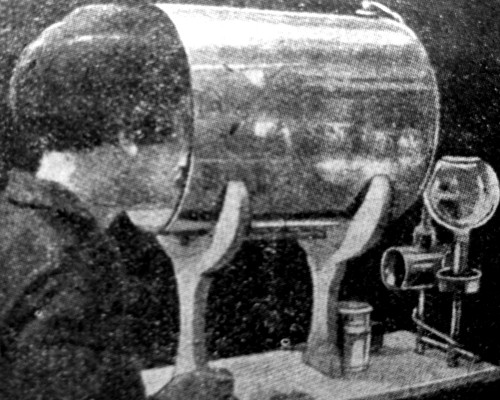

Above: 1929 Client undergoing a steam and blue light treatment in a French salon. The device appears to be a Vapofor. The two light globes in the tube are not visible.

Above: 1936 Vapofor available from the Gloria Light Company.

Above: 1944 Face steamer. Although similar to the apparatus above, this one does not seem to be using coloured lights.

See also: Red Light, Blue Light

2. Ozone: Another development was to add ozone. Ozone was believed to have a stimulating effect on the skin and/or to help combat the bacteria associated with pimples and acne. In early machines the ozone was produced by a high-frequency spark but in modern steamers this is done with ultra-violet (U.V.) light.

Above: 1936 Early vaporiser that used a spark-gap to generate ozone.

The amount of ozone produced in modern steamers with this feature is low, but as ozone is both an irritant and a poison its use is problematic, with some countries banning the sale of this type of device.

Atomisers

The second group of vaporisers generate a fine spray of water over the face. The principle behind these devices is also used in other sprays such as insecticide pumps and perfume atomisers. These work by passing a stream of air over the top of a thin tube connected to a reservoir of fluid. This creates a low pressure area on the top of the tube which draws the liquid up the tube producing a fine spray. The devices used in beauty salons generally used steam to generate the air-flow but the believed benefits of the device come largely from the fine spray not the steam.

Atomisers have two main advantages over steamers. First, as the spray is formed by atomisation not evaporation, ingredients added to the water do not have to be volatile in order to reach the face, e.g. astringents or herbal ingredients. Second, as the spray is a cooler than steam alone, this makes it useful for treating certain skin conditions where steam would be inadvisable.

It is unnecessary to expose a dry face to the drying effects of hot steam, and so we treat it with a “cooled vapour,” i.e., we spray the face with a jet of luke-warm water. … We usually put some astringent chemical (tincture of benzoin, toilet vinegar, eau de Cologne) into the cold water.

(Lázár, 1937, p. 51)

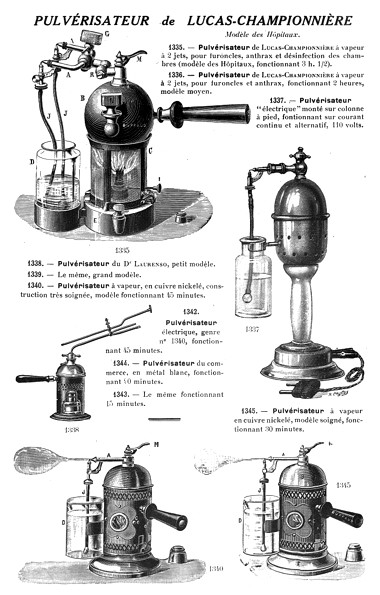

Atomisers are more commonly found in Europe, particularly France, where they are usually referred to as ‘vapourisers’ or ‘pulvérisers’. In the English speaking world they are usually called pulverisers – an Anglicisation of the French word pulvériser meaning spray.

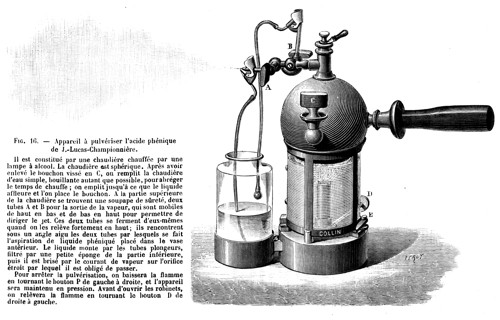

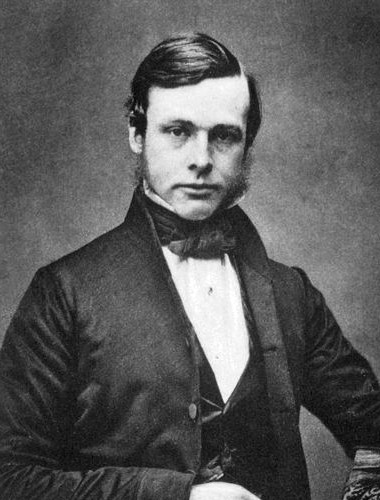

The standard for all modern atomisers is the Lucas-Championnière, named after Just Lucas-Championnière, a French surgeon, and the device he introduced into France in the 1870s. It was not designed as a beauty product but rather to spray carbolic acid (phenol) during surgery, a practice first developed by the Scottish surgeon Joseph Lister.

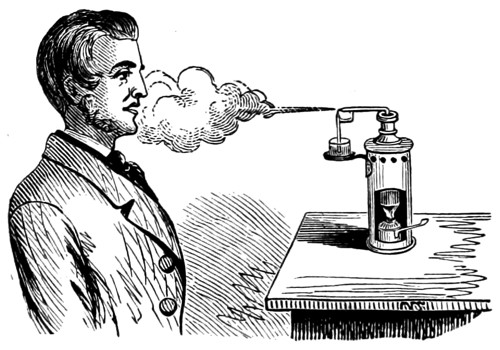

Lister had been inspired by Louis Pasteur’s germ theory to develop a disinfectant spray that he could use during surgery but needed a suitable device. The apparatus he settled on was based on an atomiser inhaler – an early nebuliser – developed by Dr. Emil Seigle in 1864.

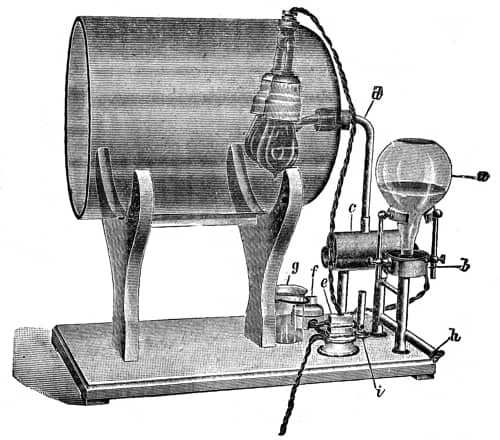

Above: 1847 Dr. Seigle’s inhaler.

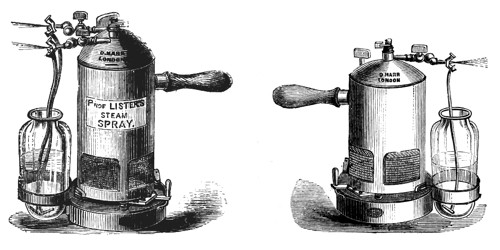

Between 1873 and 1875 Lister adapted the model provided by the atomiser inhaler to the needs of surgery. Convinced by Pasteur that air was the main vector of the germs responsible for post-operative infections, he used these devices to spray a solution of carbonic acid (phenol) into the air during the surgical procedures to disinfect the area around the wound.

Above: A Lister Atomiser.

After 1887, carbolic acid sprays were abandoned by Lister when he realised that germs carried on the surgeon, the patient, instruments and medical dressings were more likely to result in infection than those carried by the air.

Lucas-Championnière became interested in Lister’s work and, after visiting him in Glasgow in 1868, introduced Listerian principles into French surgical practice using a pulvériser (atomiser) of his own design.

Above: A Lucas-Championnière Pulvériser.

These Lucas-Championnière devices were appropriated by French beauty specialists who used them on the faces of their clients.

[T]here is no beauty treatment without atomization. It completes make-up removing, it thoroughly cleanses the surface of the skin and gives your client a pleasant feeling of “cleanliness” and relaxation.

(Pierantoni, n.d., p. 185)

By the 1930s, advice columns in French magazines were suggesting that these devices should be purchased and used at home.

Above: 1934 French vapouriser/atomiser/pulveriser.

Translated from French: “Vaporisation of the face is also a great way to cleanse the skin, making any face showing signs of fatigue, after a tiring night and day, sparkle. It’s also an excellent treatment spray after a massage. It’s easy to do at home. The electrical device that gives you all of these valuable benefits is easy to obtain and use. A small lamp heats the jet. Put hot water in the container above the lamp. Astringent and cold water in the outer cup. Turn on the power, then the tap when you hear a slight hiss; place your face over a bowl, and a fine, warm, restful rain gently sprays out. Nothing decongests the skin and cleans it more thoroughly” (French Vogue).

Perhaps the biggest issue with using French style pulverisers in a salon – apart from their cost – is that they required constant attention during a treatment. They were hand-held, had to be moved around the face, and were liable to spurt if blocked, so could not be set up and left like a modern steamer with its convenient timer and cut-off switch. This restricted the therapist from doing other things – such as mixing up a following mask – during that part of the facial.

Above: A small electric pump being used to generate a fine facial spray. Similar effects can be achieved with a hand spray.

Benefits similar to those achieved by a French pulveriser can also be achieved by spraying the face with a good pump-pack, a point clearly noted by the makers of the numerous purse-sized facial sprays currently on the market.

See also: Carbonic Gas Sprays

First Posted: 6th October 2014

Last Update: 26th August 2021

Sources

The Andrew Jergens Company. A skin you love to touch. New York: Author.

Blood, I. H. (1928). The cosmetiste: A handbook on cosmetology with special reference to the employment of electricity in the care of the hair, scalp, and face at the direction and under the supervision of W. M. Meyer (6th ed.). Chicago, IL: The W. M. Meyer Co.

Butterick Publishing Company. (1892). Beauty: Its attainment and preservation (2nd ed.). New York: Author.

Covey, D. A. (1911). The secrets of the specialists (3rd. ed.). Newark, NJ: Physicians Drug News Co.

Farbab, A. J. (1892). A good complexion. The Dawn. Sydney, March 1st, page 9.

Lázár, C. (1937). Manual of cosmetics. London: Henry Kimpton.

Mixter, M. (1910). Health and beauty hints. New York: Cupples & Leon Company.

Pierantoni, H. (n.d.). Basic knowledge of esthetics translated from the French. Paris: Les Nouvelles Esthétiques.

Roth, M. (1885). The Russian bath (2nd. ed.). London: Groombridge & Sons.

Scudder, J. M. (1874). On the use of medicated inhalations, in the treatment of diseases of the respiratory organs (3rd ed.). Cincinnati: Wilstach & Baldwin.

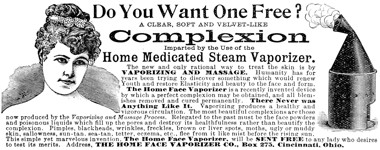

1896 The Home Face Vaporizer Company.

1900 A Sanitas Fumigator.

1904 Washing the face with a cloth (left) and using a cylinder over hot water as a steamer (right).

1906 A sponge bath with warm water.

1914 Woodbury Facial Soap recommending a steam treatment for sallow skins.

1924 Hot towels could be used instead of a steamer in a salon. Some clients preferred them but laundry costs were higher.

Steam was also used in early hair curling treatments.

1928 Steam Generator.

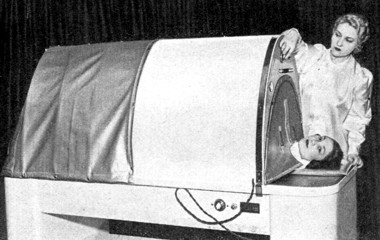

1939 An electrically powered body steamer combined with infra-red rays produced by lamps inside the cabinet. Its telescopic nature meant that it could be adjusted to any part of the body (Modern Mechanix).

1952 Home steamer.

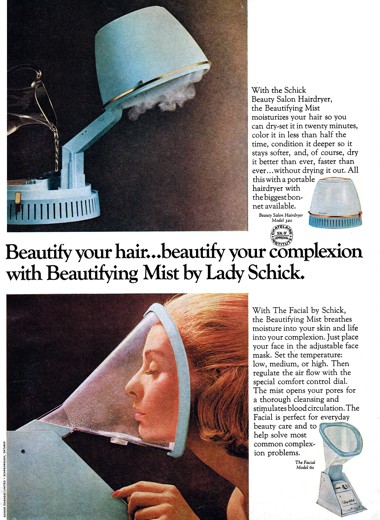

1967 Schick Beautifying Mist.

A modern steamer.

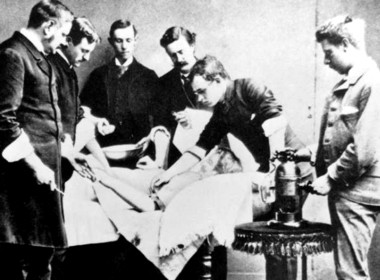

Joseph Lister [1827-1912].

1883 Physicians operating under a germicide spray according to method established by Lister.

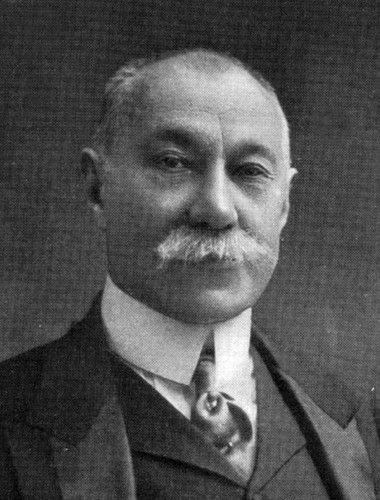

Just Lucas-Championnière [1843-1913].

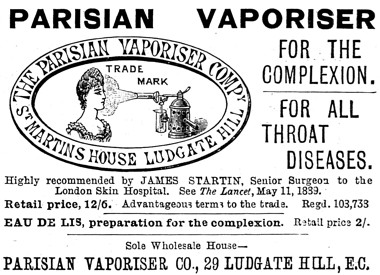

1889 Parisian Vaporiser recommended for both beauty and health benefits.

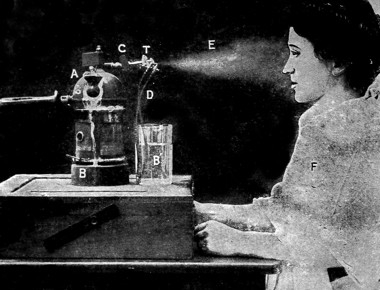

1916 An atomiser of the Lucas-Championnière type in action.

1932 A Lucas-Championnière atomiser being used in a Helena Rubinstein salon.

1934 Assorted Lucas-Championnière Pulvérisers from a French surgical catalogue. Some employ a burner to heat the water but most use electricity. They were mainly used to fumigate anthrax wards.

1937 A French apparatus for combining pulverisation with a coloured light treatment.

A perfume atomiser. These produce a fine spray using the same principle as the Lucas-Championnière Pulvérisers but use air pressure instead of steam.

A modern electrical pulveriser/atomiser.

Professional instructions for salon use:

1. Before starting an atomization, always check if the appliance is in perfect working-order: nozzles clean, correct water-level.

2. Plug into the right mains voltage: check whether the appliance corresponds to the mains voltage.

3. While you wait for the water in the boiler to come to the boil:

—pour the lotion you want to atomize in the glass beaker,

—prepare towels, cap, etc. to protect the hair and clothing of your client,

—sit your client down.

4. Give your client a special bowl with curved sides that she can hold against her neck.

—cover her hair and clothes. Put a towel around her neck to stop the atomized liquid running down her clothes.

5. Ask your client to close her eyes, without contracting her features.

6. If there is a safety valve controlling the jet of steam, let out some steam and control the pressure and strength.

If the nozzle is fixed, wait till the jet of steam is strong enough before starting the atomization.

7. Place the beaker with the liquid you wish to atomize in the right position and dip the small plastic tube in it. The liquid is drawn up and will mix with the steam.

8. Wait a few seconds before directing the steam towards your client’s face and make sure no boiling water, but only steam, spurts out.

9. When you are certain the appliance is working correctly, hold it at a distance of 25-30 cm from your client’s face and start atomization. Keep your atomizer perfectly straight. Move it in circles, all around the face, front and sides, bathing the whole surface of the skin in the fine mist. This condenses on the epidermis and forms myriads of small droplets.

10. Take a small sponge in your free hand and wipe the droplets off the sensitive areas, like the top of the nose.

N.B.: Some very nervous people may experience a choking sensation. To avoid this, you can hold a sponge a few millimeters away from the nasal fossae, while atomizing.

11. After one or two minutes, stop the atomization and ask your client to keep her eyes shut.

12. Place the atomizer on a small table, remove the bowl from your client’s hands, dry her face and lie her down in a relaxed position.

13. Pat the skin carefully dry, without rubbing. You can proceed as follows: hold a small towel in your left hand, another in your right hand and place the first on the forehead, the second one on the lower part of the face, pressing down gently and asymmetrically. Continue until the skin is completely dry.

14. Clean the atomizer and prepare it for the next treatment.

(Pierantoni, pp. 186-188)

Mala Rubinstein [1905-1999] demonstrating the use of a pulveriser during a facial treatment.

Pump-pack face spray. Small purse-sized atomisers like this can produce effects similar to those generated by a pulveriser.