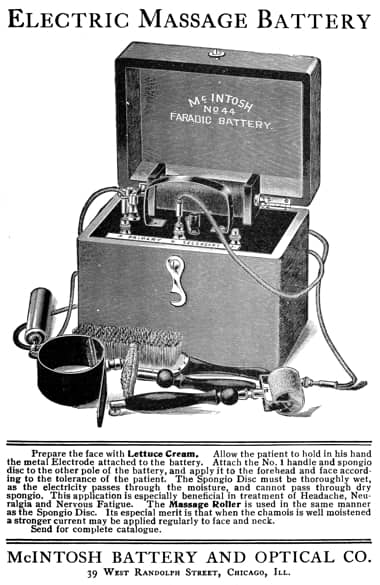

Faradic Treatments

By 1900, some beauty establishments were using faradic batteries to provide their clients with ‘electrical massages’. Like other electrical beauty treatments this practice came from similar treatments developed and used in nineteenth-century medicine.

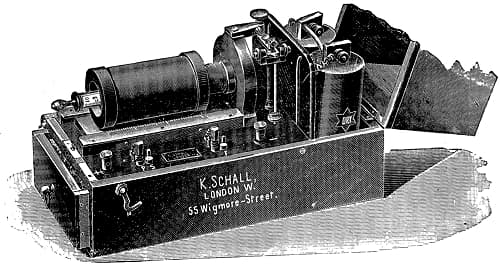

Faradic batteries

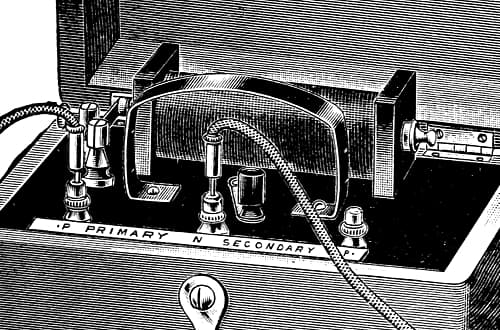

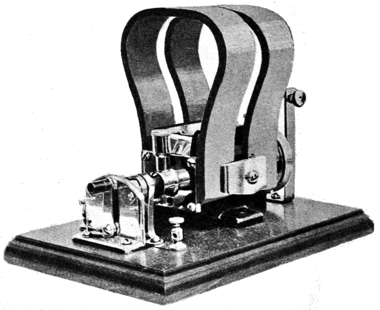

Faradic batteries combined a wet or dry cell battery with an induction coil and an automatic circuit breaker.

Above: 1902 Faradic Battery. Induction coil with primary and secondary coils and soft iron core (left), interrupter (center), and two dry-cell batteries (right).

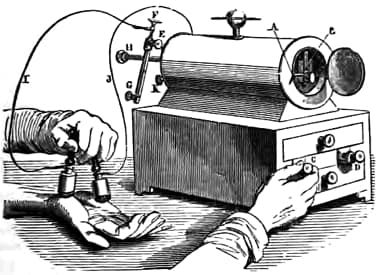

The induction coil consisted of a primary coil of thick, insulated wire wound around a wooden bobbin that encased a soft iron bar, and a secondary coil, of thinner, insulated wire also mounted on a hollow wooden bobbin that fitted over the primary coil. The proximity of the two coils enabled the magnetic field in primary coil to induce an electrical current in the secondary coil, the field in the primary coil being strengthened by one created in soft iron core.

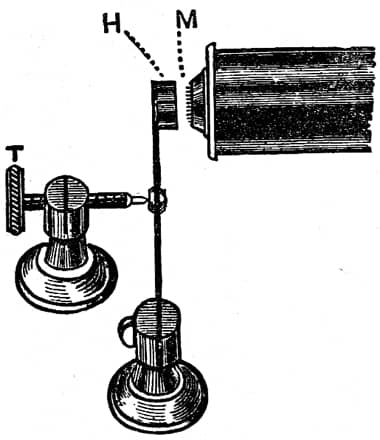

The automatic circuit breaker turned a continuous galvanic current in the primary coil into a rapidly interrupted current and was an essential component in the process of inducing a series of higher voltage electrical impulses in the secondary coil. A range of different circuit breakers (interrupters) were developed but a simple mechanical version which used a metal spring was common.

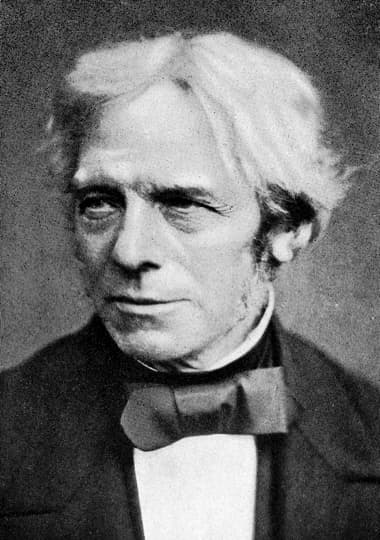

Guillaume Duchenne

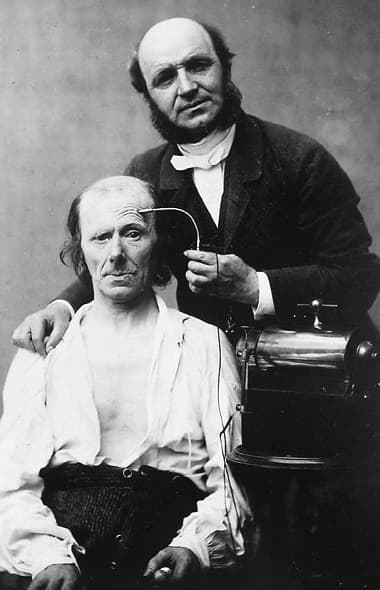

A battery along the lines described above was constructed by Guillaume Duchenne, a French neurologist, in the early nineteen century and was used by him to contract facial muscles during his study of facial expressions.

This was not the first device Duchenne used to contract facial muscles. He started out by inserting metal needles into the muscles but found that he could administer the electric current less painfully using moistened electrodes placed on the surface of the skin. He tried both galvanic and induced currents in his experiments but preferred the induced, calling it a faradic current after Michael Faraday, the English scientist who discovered the principle of induction in 1831.

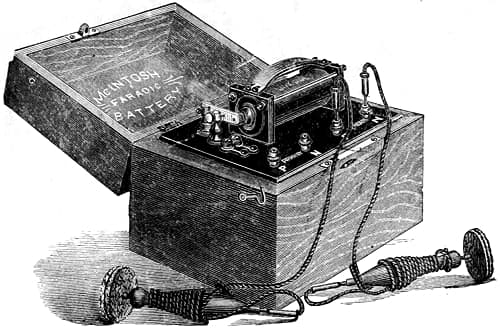

Duchenne’s book, ‘De l’électrisation localisée et de son application à la physiologie, à la pathologie et à la thérapeutique’, outlining his work on facial expressions was published in 1855. It was accompanied by a startling series of images produced using the new medium of photography. Together these publications generated a good deal of interest into the therapeutic uses of faradic currents. By the 1880s, the medical use of faradic batteries was widespread with many different models readily available from a number of medical supply companies.

Above: 1888 McIntosh Physicians Faradic No. 1 with induction coil, interrupter and electrodes. A range of different interrupters were developed over the years but a simple mechanical version using a metal hammer and spring was common.

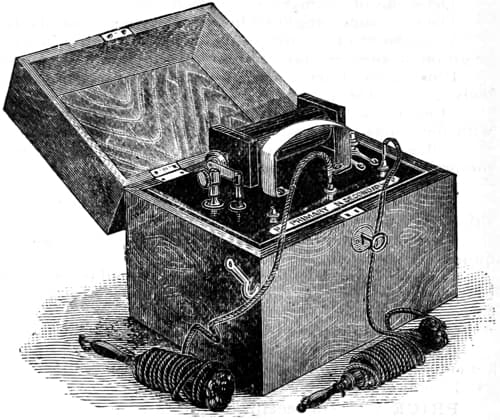

Some companies also made smaller, cheaper versions for use in private homes and beauty salons.

Above: 1888 McIntosh Family Faradic.

Operation of faradic batteries

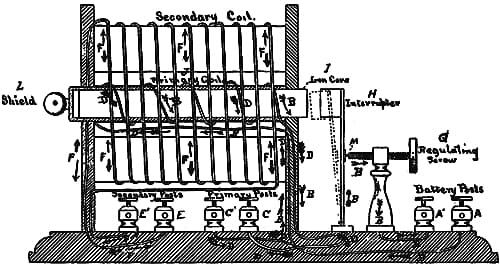

A faradic battery using a mechanical interrupter worked as follows:

One end of the primary coil of the induction coil was connected to a wet or dry-cell battery, the other to the interrupter which pressed against a screw running through a metal post attached to the other pole of the battery.

Above: Current flow in a faradic battery (Herdman & Nagler, 1898).

When the circuit was complete, the electric current from the battery passed through the contact screw, the interrupter and the primary coil (the make). This created a magnetic field in the primary coil and turned the soft iron core into an electro-magnet which together induced a weak current in the secondary coil.

However, as soon as the soft iron core was magnetised it attracted the metal interrupter which broke the circuit at the screw point (the break). When the circuit was broken, the magnetic field produced by the primary coil collapsed and the current in the secondary coil reversed its direction producing a strong electrical pulse.

Once the current flow was broken, the soft iron core also demagnetised, allowing interrupter to spring back and establish the circuit once more. This process repeated many times per second with the interrupter springing back and forth creating a buzzing sound characteristic of faradic coils.

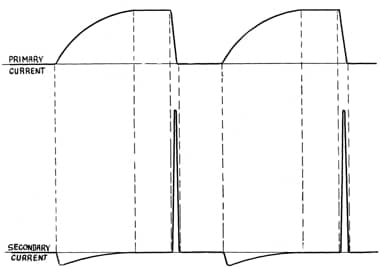

Primary and secondary faradic currents

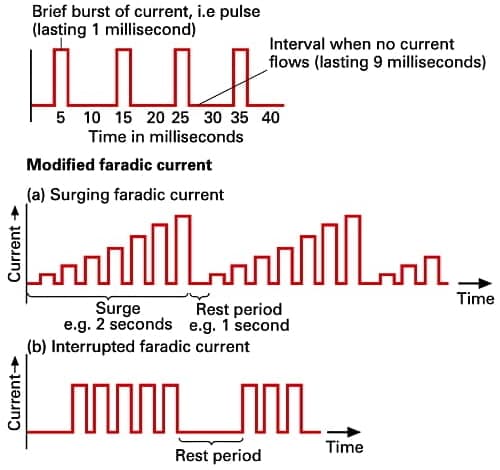

Not every faradic battery had this option but it was possible to derive an electrical current from both the primary and secondary coils.

Above: 1904 Close view of a faradic battery with outlets from both the primary and secondary coils.

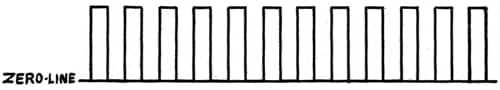

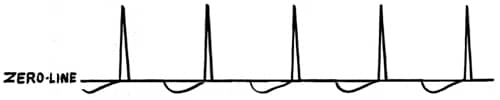

The electrical current from the primary coil was referred to as the primary faradic. However, as it was not produced by induction it is better described as a galvanic (direct) current with frequent breaks – an interrupted, direct current. Like other galvanic (direct) currents it was polar, producing acid at the positive pole and an alkali at the negative.

Above: Primary faradic. An interrupted, galvanic (direct) current from the primary coil as the current is turned on and off by the mechanical interrupter.

See also: Galvanic Treatments

The current from the secondary coil was called the secondary faradic and was a true induced current. It was interrupted because, like the current in the primary coil, the flow of electricity was frequently made and broken; alternating because the flow of electricity during the make was in the opposite direction to the break; and asymmetrical because the break current was stronger than the make. It would now be referred to as an asymmetrical, interrupted, alternating current.

Above: Secondary faradic: An asymmetrical, interrupted, alternating current from the secondary coil as the current is turned on and off by the mechanical interrupter.

Although the secondary faradic was the only true induced current, both the primary and secondary faradic currents were capable of producing the muscle contractions and this created some confusion amongst beauty therapists. The secondary (true) faradic current was viewed as less irritating so, in general, the rule was to use the secondary faradic on the face and restrict the primary faradic to the scalp.

The question often arises as to which Faradic current should be used, primary or secondary. Either one may be used; however, it is generally conceded that the secondary, having more intense pulsations and practically no polar effect, is less irritating than the primary. Such being the case, the Primary would be preferable where a very stimulatory massage is required, as in scalp work, and the Secondary would fulfill more perfectly the requirements for muscle toning for the face, since it is slightly less irritating and causes a reaction of deeper tissues.

(Stingley, 1939, p.28)

Benefits

Faradic treatments were said to ‘exercise’ the muscles, strengthening and firming them while stimulating the circulation to bring in extra nutrients and remove wastes.

The vibratory effect of faradism is extremely beneficial, so the use of current can be recommended in the massage of the scalp and face. The nerves are stimulated; dormant or sluggish muscles are revitalized and made firm; the circulation of the blood and lymph is made to flow more swiftly through the regions treated; and all the essential processes of metabolism (i.e., the building up and normal decay of the tissues) are made to function properly.

(‘The science of beautistry,’ 1932, pp 199-200)

When applied to the face this current penetrates the tissues, nerves, and muscles charging them with an electric current which tones and activates them, causing them to contract involuntarily, thus bringing and invigorating supply of blood to that part of the face and affording splendid stimulation. If constantly used firmness and plumpness of the muscles are bound to result in response to the continued contraction and many of the lines and crow’s feet that herald the approach of middle age, gradually disappear.

(Stingley, 1939, pp. 27-28)

These benefits were similar to those attributed to massage. Faradic treatments were therefore seen as an electrical alternative to massage and the machines sold to beauty salons were often described as ‘electric massage batteries’. Treatments with the faradic battery did not necessarily replace a hand massage which could be done before the faradic treatment or in conjunction with it.

See also: Massage, Wrinkles and Double Chins

Treatments

When first used in salons, ‘electrical massages’ were restricted to the face, throat, décolletage and scalp. Like high-frequency treatments these could be done directly using an electrode or indirectly with the current running through the operator’s fingers.

See also: High Frequency

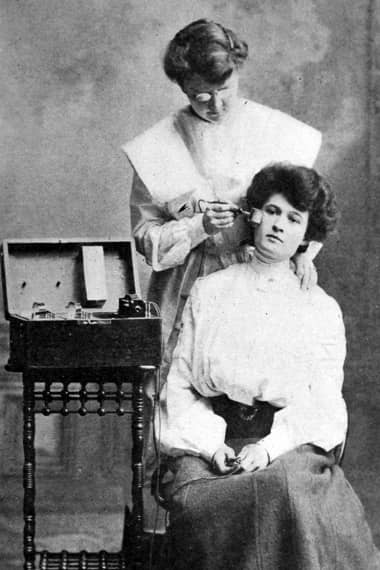

Direct method

When applying a faradic current directly, the electrode selected varied according to the region being electrically massaged. An electric hair brush – not to be confused with the glass electrode rake used in high-frequency treatments – could be used to stimulate the scalp; roller electrodes, similar to those used in iontophoresis, could be run over the face to tighten facial muscles, across the neck to reduce double chins, or over the chest area to firm the breasts; while ball electrodes could be used on motor points to stimulate specific muscles.

Above: Direct faradic treatment with a roller electrode.

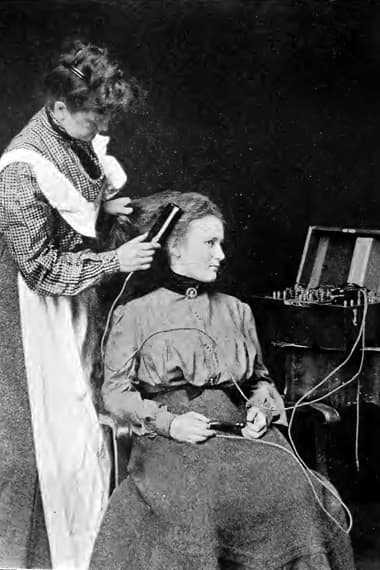

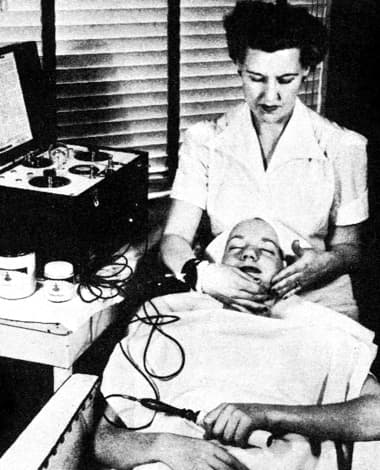

Indirect method

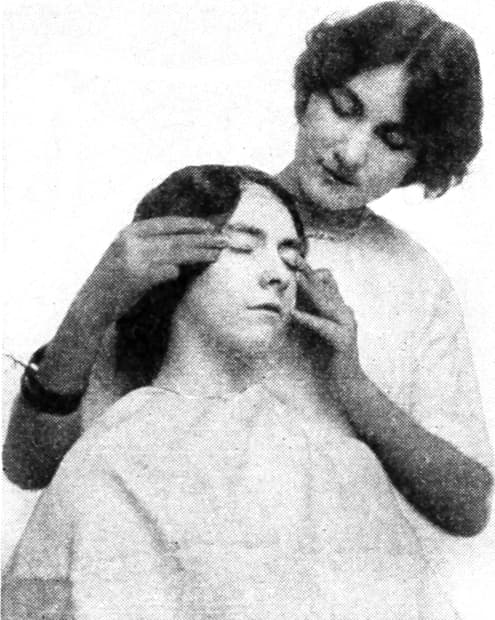

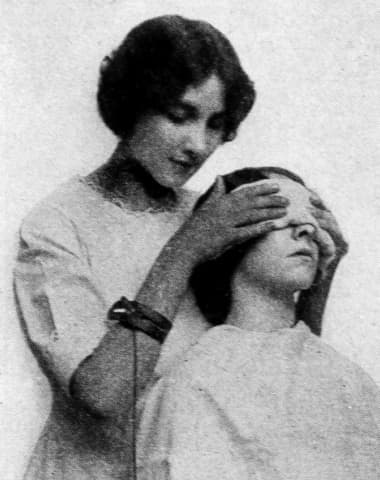

The client was given a moistened cloth-covered carbon electrode to hold while the operator fastened a circular electrode to her wrist which allowed the current to pass through her fingers as she ran her fingers over the skin.

Above: Indirect faradic treatment.

In connection with massage treatments the faradic current is always employed while the manipulations are being given. The patient holds the moistened cotton-covered carbon electrode in her hand, while the operator has the wrist electrode fastened to her own arm.

The current thus passes through the fingers of the operator to the patient producing a decidedly stimulating and restful effect.(Lloyd, 1914, p. 86)

This procedure was more popular than the direct method in early beauty salons with some salons using it exclusively.

Discomfort and pain

Faradic currents produce skin sensations beneath the electrodes and this could be uncomfortable for some clients.

The strength of the current must always be gauged by the sensations of the patient. Never allow it to become in the least painful and always inquire as to which strength of the current is most enjoyable.

A current that is mild and enjoyable over the fatty portions of the cheek or at the back of the head, will be most unbearable about the mouth, over the forehead and around the eyes.

When the patient has many filled teeth the use of this current even in a mild form sometimes produces a toothache and cannot be used.

If used at all strong about the eyes and especially when the finger tips are engaged in manipulating the eyebrow, a sharp pain often shoots through the head alarming the sensitive patient and spoiling much of the effect of the treatment. A little caution will soon remedy this.(Lloyd, 1914, p. 86)

Care therefore had to be taken when using these machines particularly during facial treatments.

Other developments

Medical use of electric currents to treat weak or damaged muscles that began in the nineteenth century continued through into the twentieth. During this time doctors and others experimented with a range of different electrical currents, modified the use of those currents and combined different types of currents.

In 1888, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg [1852-1943], described a new device to generate muscle contractions he was using at his world-renowned Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan. It passed a galvanic (direct) current through a rhythmically varying resistor that periodically reversed the direction of the current. This current was later termed sinusoidal by Jacques-Arsène d’Arsonval [1851-1940], the French physician and physicist, due to the sine shape of the electrical trace.

Like the primary and secondary faradic currents, sinusoidal currents produced muscular contractions, but did so with less discomfort to the client. Medical supply companies were soon producing sinusoidal machines for use by the medical profession but early beauty salons generally stayed with their faradic batteries. The reasons for this appears to have been familiarity and cost. The simplicity, cheapness and portability of faradic batteries ensured that they remained a popular beauty device for producing ‘electrical massages’ for many years.

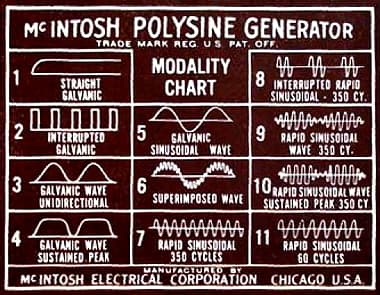

Things began to change in the 1920s. By then, machines were being produced that made the selection and use of a wide variety of electrical modalities a simple matter of turning one or more dials.

Above: 1926 Chiropodist using a sinusoidal current from a McIntosh Polysine Generator on the leg of a client.

Devices like this, and their successors, would eventually replace the older faradic batteries. They first appeared in better-equiped salons where they were used to provide a range of electrical treatments. For example, in the 1930s, Helena Rubinstein used a H. G. Fischer Low Volt Generator to supply her Electro-Tonic Mask which used a galvanic (direct) current to activate the blood circulation, nourish and firm the tissues, and her Electro-Passive Treatment which used a slow sinusoidal current to contract facial muscles and improve facial contours.

Above: 1941 Galvanic Electro-Tonic Treatment in a Helena Rubinstein salon using a H. G. Fischer Low Volt Generator.

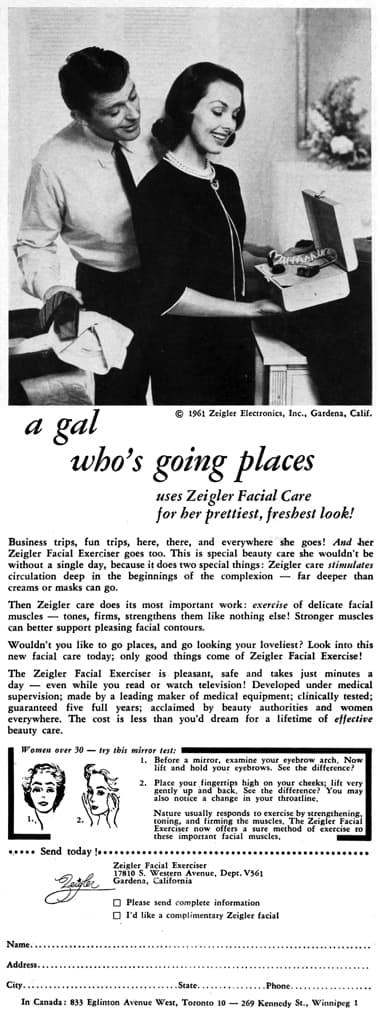

The idea of using electrical currents to ‘passively exercise’ muscles also saw these electrical devices used on the body in weight control and ‘body shaping’ treatments. This began in earnest in the 1930s and, by the 1950s, a profusion of specialist devices became available for use by physiotherapists and beauty therapists.

Above: 1957 Medcolator being used to treat an athlete.

Above: 1961 Woman having a Rejuvenator Treatment in the Joy Burne Salon, London, to firm the upper arm while her hair dries.

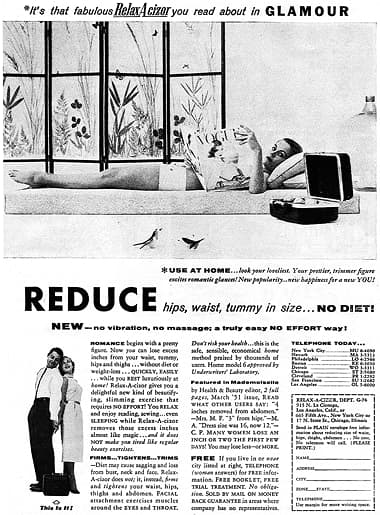

Cheap, passive-exercise devices were also sold to the general public, a good example being the Relax-A-Cisor which promised weight loss and body toning without physical exercise or dieting.

Modern salon machines that use muscle contraction (passive exercise) as part of a weight loss, body contour or cellulite treatment combine multiple outlets, connected to pads for placement on relevant parts of the body, with electronic control systems that create a wide assortment of electrical modalities/wave forms.

Above: Some of the wave forms produced by a modern ‘faradic’ beauty device used in salons in weight reduction or other treatment programs.

Some of these machines, and the currents they produce, are described as ‘faradic’ or ‘faradic type’ even though they are variations of interrupted, direct current. Like the use of the word ‘galvanic’ this is a reference to an era long passed.

See also: Interferential Treatments

First Posted: 14th January 2020

Last Update: 30th December 2021

Sources

Gottschalk, F. B. (1904). Practical electro-therapeutics. Chicago, IL: T. Eisele.

Herdman, W. J., & Nagler, F. W. (1898). A laboratory manual of electrotherapeutics. Ann Arbor, MI: George Wahr.

Kovács, R. (1935). Electrotherapy and light therapy (2nd ed.). London: Henry Kimpton.

Kovács, R. (1949). A manual of physical therapy (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger.

Lloyd, E. (1904). The Marinello text book (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: Marinello Company.

McIntosh Battery and Optical Company. (1903). The skin. Its care and treatment. Chicago, IL: Author.

W. M. Meyer Co. (1936). The cosmetiste: A textbook on cosmetology with special reference to the employment of electricity in the care of the hair, scalp, face, and hands, also permanent waving and hair curling (9th ed.). Chicago, IL: Author.

Moler, A. B. (1905). The manual on barbering, hairdressing, manicuring, facial massage, electrolysis and chiropody as taught in the Moler system of colleges.

Morris, H. (1946). Medical electricity for massage students (3rd ed.). London: J & A. Churchill Ltd.

Overall, G. W. (1890). Practical electricity in medicine and surgery. Memphis, TN: Press of Memphis Printing Company.

Rowbottom, M., & Susskind, C. (1984). Electricity and medicine: History of their interaction. San Francisco, CA: San Francisco Press, Inc.

The science of beautistry. Official textbook approved for use in all the national schools of cosmeticians affiliated with Marinello. (1932). New York: The National School of Cosmeticians, Inc.

Simmons. J. V. (1989). Science and the beauty business. Volume 2. The beauty salon and its equipment. London: The Macmillan Press Ltd.

Stingley, G. (1939). Electricity manual for beauty culture (10th revised ed.). Chicago, IL: Author.

Stingley, G. (1957). Electricity manual for beauty culture (15th ed.). Maywood, CA: Author.

Stafford, A. M. (1926). A handbook of physio-therapy. Chicago, IL: Medical and Surgical Publishing house.

Strong, F. F. (1908). Essentials of modern electro-therapeutics: An elementary text-book on the scientific therapeutic use of electricity and radiant energy. New York: Rebman Company.

Turrell, W. J. (1922). The principles of electrotherapy and their practical application. London: Henry Frowde and Hoder & Stoughton.

Michael Faraday [1791-1867]. Faraday discovered the principle of induction in 1831 and electrical currents produced by these coils were called faradic currents to honour him.

1862 Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne [1806-1875], also known as Duchenne de Boulogne, producing muscle contactions of the facial muscles with faradic electricity produced by the induction coil displayed in the photograph.

Above: An induction coil with circuit breaker and electrodes used by Duchenne to produce muscle contractions.

A mechanical interrupter used with an induction coil. The screw (T) could be used to close the gap between the metal plate on the interrupter (H) and the end of the projecting end of the soft iron bar (M) to change the speed of the make and break cycle.

1904 McIntosh Electric Massage Battery, a faradic battery for use in beauty salons.

Electrical currents produced by the primary (inner) and secondary (outer) coils over two make and break cycles. The primary current is an interrupted, direct (galvanic) current. The secondary current is a faradic (induced) current (Kovacs, 1935).

Direct faradic treatment using a roller electrode in a Marinello salon (Lloyd, 1903).

Direct faradic treatment using the hairbrush electrode in a Marinello salon (Lloyd, 1903).

Indirect facial massage using a faradic current in a Marinello salon (Lloyd, 1903).

1904 Faradic eye treatment – massage.

1904 Faradic eye treatment – applying a bandalette.

Faradic muscle treatment of a soldier from the First World War.

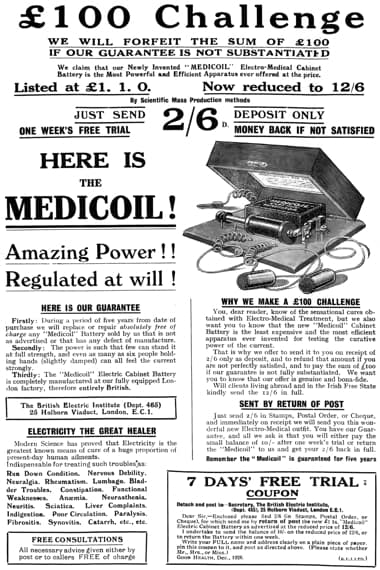

1928 Medicoil. This faradic device, built for use in the home, promised cures for: run down condition, nervous disability, neuralgia, rheumatism, lumbago, bladder troubles, constipation, functional weakness, anaemia, neurasthenia, neuritis, sciatica, liver complaints, indigestion, poor circulation, paralysis, fibrositis, synovitis, and catarrh. Many of these conditions reflect similar uses of faradic currents by the medical profession at the time.

Sinusoidal machine used by Dr. John Harvey Kellogg.

1935 Helena Rubinstein Electro-Passive Treatment.

Above: Modality Chart for a McIntosh Polysine Generator showing the range of galvanic and sinusoidal currents it could produce.

1948 Demonstation of a faradic body treatment to students in a Deliah Collins training salon.

Medical treatment on a soldier from the Second World War using a McIntosh Wall Plate.

Faradic indirect facial using a McIntosh Wall Plate. The machine could produce galvanic, faradic and sinusoidal currents (Stingley 1957).

1955 Mercolator.

1956 Relax-A-Cisor.

Carlton Faradic Device with face and body electrodes (Morris, 1987).

Faradic body contour treatment (Morris, 1987).

1961 Zeigler Facial Exerciser.