Dry Skin Treatments

In 1987, Gérald E. Piérard from the Department of Dermatology, University of Léige, Belgium posed the question ‘What does “dry skin” mean?’

The term “dry skin,” so frequently used by cosmetologists and patients consulting a dermatologist, has never been defined in a reproducible way. Too often, there is a confusion between the concept of dry, meaning without water or moisture, and the aspect of rough, brittle scaly skin.

(Piérard, 1987, p. 167)

Two years later, Piérard raised the question again ‘What do you mean by dry skin?’, and highlighted a distinction between the topical treatments used by the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries.

Claims of some cosmetologists would have us believe that bringing water to the skin with ‘moisturizers’ is the solution to the problems of dry skin. The pharmaceutical industry usually has an opposite view when it proposes an ointment rather than a cream to treat the chronic dry type of various dermatitides.

(Piérard, 1989, p. 1)

The distinction Piérard made in 1989 between the cosmetic industry’s preference for moisture and the pharmaceutical industry’s reliance on oils in ointments was then relatively recent, only dating from the development of the moisturiser in the 1950s.

See also: Moisturisers

Before then, the prevailing view in the beauty industry was that dry skin was primarily due to a deficiency of natural oils not moisture, the result of under-active sebaceous glands failing to produce enough oily sebum.

Dotted over nearly the whole area of the skin are tiny depressions out of which hairs grow. … Attached to these depressions are certain glands which manufacture a secretion of an oily and waxy nature called “sebum”, which is Nature’s lubricant for both the hair and the skin. When the sebaceous glands, as they are called, produce too little of this necessary lubricant, a dry skin is the result.

(Redgrove, 1931, p. 18)

When the sebaceous glands produce too little oil the skin is dry.

(Gordon, 1934, p. 3)

The skin is dry and sensitive if it does not receive the proper lubrication from the oil glands.

(Smith & Rockwood, 1935, p. 102)

The idea that dry skin was due to a lack of oil was also prevalent amongst cosmetic chemists of the time.

If the sebaceous glands secrete sufficient natural oil, the skin is normal; if insufficient the skin becomes dry.

(deNavarre, 1941, p. 626)

[A] ‘dry” skin … lacks the normal amount of protective secretion from the sebaceous glands.

(Harry, 1944, p. 356)

The lack of oil resulted in skin that was rough, scaly and flaky. Unless corrected, it could also lead to increased skin wrinkling, a primary concern of the beauty industry.

The natural oils that keep the face fresh and young-looking are not in sufficient abundance in the dry skin to prevent flaking, coarsening, wrinkling. Unless these oils are restored, then preserved constantly—by wise cleansing, delicate soothing and careful protection—delicate, dry skin types are apt to fade fast.

(Harriet Hubbard Ayer, 1934, p. 18)

A dry skin has a deficiency of oil in the sebaceous glands and has a tendency to wrinkle. When the fibrous structure of the skin is deprived of nourishment it loses elasticity and shrinks. The epidermis has no elasticity and therefore becomes too large, and creases form which are commonly known as wrinkles.

(Joslen, 1937, p. 36)

Moisture

Although early beauty practitioners thought that a deficiency of oil was considered to be the primary cause of dry skin, they also knew that moisture loss was part of the problem. Dry skin was known to be exacerbated by conditions where the humidity was low, such as during hot, dry summers and cold, dry winters. In addition many creams and jellies that used glycerine to soothe and protect the skin from chapping and dryness, were known to work because of glycerine’s ability to absorb water.

[G]ycerine is a hydroscopic liquid, that is to say, it possesses the property of absorbing moisture from the atmosphere, and it is this characteristic which every woman should consider when buying a day cream. For those who have a dry skin, a small percentage of glycerine in the vanishing cream is an advantage.

(Poucher, 1926, p. 35)

Also see: Glycerine Creams and Jellies

Although moisture loss was acknowledged, early beauty practitioners thought that replenishing the skin’s oil was the best solution to the problem of dry skin, a position not too dissimilar to the views of dermatologists and pharmacists of the time.

The oils in sebum, rather than the outer layer of the skin (stratum corneum) were thought to be the main barrier to water loss from the skin and oil, rather than water, was believed to keep the skin soft and pliant. This view is understandible as applying a lubricating oil on the skin made it feel softer and smoothed the appearance of rough skin. Oils were also thought to be nourishing which is why they were used in skin foods and muscle oils to help restore the natural functioning of the skin and reduce skin wrinkling.

The epidermis, or cuticle, is the outer layer of the skin and is exposed to the air on one side and attached to the corium on the other. This exposure to the air naturally keeps the outer layer in a drier condition and it is due to this fact as well as to the application of friction that the constant casting off of scales occurs. Ordinarily this process is barely perceptible, but when the secretion of oil is not sufficient to keep the skin moist, this scaliness becomes extremely objectionable and great flakes peel off continually, causing the face to look rough and coarse. Under the influence of an irritant or where there is made an attempt to bleach the skin, the same excessive flaking occurs until the applications cease. When the condition is extremely obstinate constant inunctions of oil are necessary in order to keep the skin in even a presentable condition. Hence the value of the flesh or skin foods in cases of this description, as the best of them are made from the finest oils and are readily absorbed by the skin.

(Lloyd, 1904, pp. 15-16)

Among its other functions the skin serves as a protective covering to the body. But it is impossible for the delicate tissue to successfully resist the attacks from the outside, unless it is assisted by the oily secretions with which Nature anoints it. These also hinder evaporation of the skin’s moisture and thus prevent it from becoming dry and lustreless, rendering it less vulnerable and susceptible to injury. On the other hand, defective secretion causes loss of its elasticity and mobility. The thickness of the surface layer increases, making the skin harden. And this condition naturally becomes worse when the atmosphere is dry and the skin less active.

(Helena Rubinstein, c.1908, p. 8)

See also: Skin Foods and Muscle Oils

Treatments

Early beauty treatments for dry skin varied but most followed logically from the idea that the main problem was a lack of natural oil.

First, clients were recommended to avoid anything that might strip too much oil from the skin and worsen the problem, including harsh soaps or preparations made with large amounts of alcohol like Eau de Cologne.

Second, facial treatments to improve the overall condition of the skin were used to restore the normal flow of natural oils from the sebaceous glands. This included using a dry skin cleanser to unblock the pores of the sebaceous glands; nourishing the skin with skin foods, muscle oils and/or night creams to ensure it had enough oil to produce sebum; massaging or patting the face to improve blood flow; and stimulating the skin into activity with tonics, astringents and/or circulation creams.

The dry skin needs thorough, gentle cleansing, but do not coddle it. Wake up those lazy glands with stimulating lotions. Then when a quickened flow of rich blood is rushing through every tiny blood vessel, massage in generous quantities of tissue or night cream. Leave on these creams while you bathe, while you’re tidying up your room. Let them remain on your skin overnight, and then you will enjoy a true beauty sleep. Avoid unwise exposure to the sun; it robs the skin of its oils and moisture. Watch out for winds; they too dry and harshen your skin. Never go out without first using a protective preparation that will actually shield your skin from the weather.

(Rubinstein, 1936, p. 36)

Third, the perceived lack of oil could be supplemented with a suitable oil-rich night and/or day cream, the later also helping to protect the skin from the elements when venturing out.

Dry skin creams

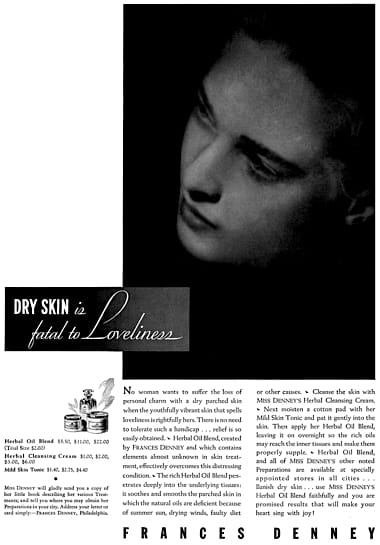

In the 1930s, many cosmetic companies began producing creams specifically formulated for dry skin. These were to be used instead of skin foods but could be combined with muscle oils in skin showing signs of early wrinkles. American examples included: Frances Denney’s Herbal Oil Blend (1930); Marie Earle’s Nurimor Dry Skin Cream (1935); Kathleen Mary Quinlan’s Dry Skin Cream, Primrose House’s Dry Skin Mixture, and Richard Hudnut’s Derma-Sec Formula for Dry Skin (1936); Barbara Gould’s Special Dry Skin Cream, and Rose Laird’s Dry Skin Cream (1938); Dorothy Gray’s Dry-Skin Lotion (1940); and Pond’s Dry Skin Cream (1941).

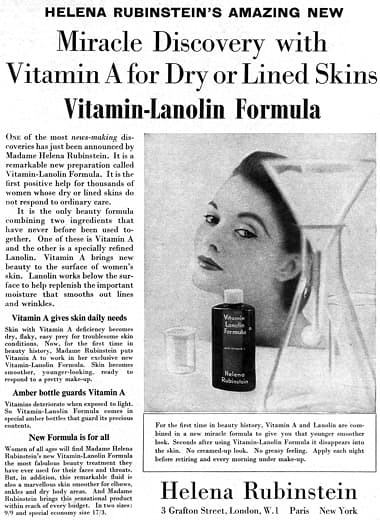

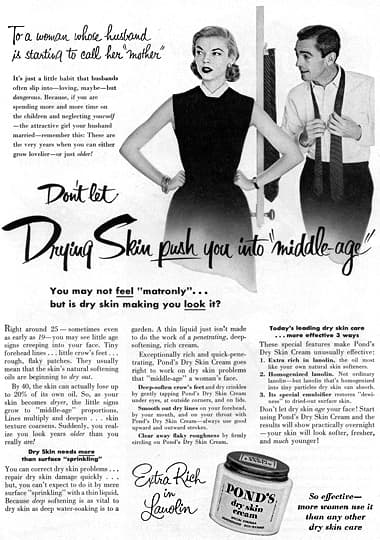

These dry skin creams were generally formulated with additional oils and/or lanolin. Lanolin was believed to be similar to human sebum, deeply penetrating and a valuable ‘skin food’ so was considered an ideal sebum replacement.

Lanolin Cream Lanolin, anhydrous 33 Soft paraffin (white “vaseline”) 33 Orange-flower-water or rose-water, undiluted 33 Perfume 1 (Redgrove, 1931, p. 78)

The reasoning behind the use of these creams may be faulty by modern standards but as they contained occlusives they would have functioned as moisturisers. Many formulations also contained glycerine or other humectants making them even more effective as skin conditioners.

Dry skin and roughness

The plethora of American dry skin creams introduced in the 1930s and 1940s was probably a response to an increased incidence of dry skin in that country. Most American beauty experts and cosmetic chemists of the time put this down to an increased exposure to warm, dry air resulting from a greater use of central heating. However, increased sun exposure was more likely to have been the main factor. Fashion changes that revealed more skin and the increased incidence of sunbathing led to rising levels of sun damage. Consequently, more women began show evidence of one of the classic symptoms of sun damage, increased ‘skin roughness’ caused by abnormal desquamation, generally described as dry skin.

Some beauty practitioners of the time recognised that not all dry skin conditions could be fixed with oils alone. In her 1941 book on Beauty Culture, published before the arrival of the moisturiser, Florence Wall [1893-1988] followed the normal practice of including an oil treatment in a dry skin facial but suggested adding exfoliation if the condition was severe.

As in the standard treatments with the following variations:

a) For dryness without roughness

After cleansing the skin, adjust eye pads in place. Then

1. Mix two tablespoonfuls each of emollient cream and muscle oil in a small dish and warm it (under infra-red or other heating device) until it forms a smooth fluid.

2. Soak the gauze square, or the strips, in the oil and place them on the face and well down over the neck, leaving a small opening below the nostrils.

3. Adjust heater over the face at a comfortable distance and pat the face all over, following the general lines of massage for three to five minutes.

4. Remove gauze, apply sufficient additional emollient cream, for free lubrication, and continue with massage as in the standard treatment.

b) For dryness with roughness

After cleansing the skin,

1. Apply emollient cream all over the face and neck.

2. Moisten a small cotton pad in warm water, squeeze it almost dry, dip it into the salt or pumice powder and go all over the skin in circular friction, following the lines of massage. Use the abrasive generously.

3. Remove cream with tissues, and sponge skin with warm water to remove all traces of salt or pumice.

4. Apply emollient cream again, apply eye pads, adjust heating device and proceed with massage. Warm oils.

5. Before removing cream, saturate gauze (piece or strips) in mixture of oils, and adjust mask, as described above.

Remove cream, sponge skin, and complete as in standard treatment.(Wall, 1941, p. 473)

Moisturisers

The arrival of the moisturiser changed many beauty ideas for treating dry skin and hydration now became the recommended treatment. However, moisturisers are a temporary fix requiring daily application so exfoliation might be a longer-lasting treatment, particularly for rough skin showing early signs of sun damage. However, if used, caution should be advised as exfoliation is not without some risks. Removing surface skin cells also strips the skin of the protective melanin pigments that these cells might contain.

See also: Moisturisers

First Posted: 30th August 2022

Last Update: 14th February 2023

Sources

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston, MA: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.

Gordon, J. (1934). Home beauty treatments solving every woman’s beauty problems. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head Ltd.

Harriet Hubbard Ayer. (1934). Beauty for all [Booklet]. Montreal: Author.

Harry, R. G. (1944). Modern cosmeticology (2nd ed.). London: Leonard Hill.

Helena Rubinstein. (c.1908). Beauty in the making [Booklet]. UK: Author.

Joslen, S. (1937). The way to beauty: A complete guide to personal loveliness. London: Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd.

Keithler, W. M. R. (1956). The formulation of cosmetics and cosmetic specialties. New York: Drug and Cosmetic Industry.

Kromayer, E. (1930). The cosmetic treatment of skin complaints with special reference to physical therapy and scarless methods of operation. London: Oxford University Press.

Lloyd, E. (1904). The skin. Its care and treatment (2nd ed.). Chicago: McIntosh Battery and Optical Company.

Piérard, G. E. (1987). What does “dry skin”means? International Journal of Dermatology, April, 26(3), 167-168.

Piérard, G. E. (1989). What do you mean by dry skin? Dermalogica, 179, 1-2.

Poucher, W. A. (1926). Eve’s beauty secrets. London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.

Redgrove, H. S. (1931). The cream of beauty. London: Heinemann.

Rubinstein, H. (1936). This way to beauty. USA: Dodge Publishing Company.

Rubinstein, H. (1964). My life for beauty. London: The Bodley Head Ltd.

Smith, A., & Rockwood, R. (1935). Modern beauty culture. New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Thomssen, B. S. (1947). Modern cosmetics (3rd ed.). New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

Wall, F. E. (1946). The principles and practice of beauty culture (2nd ed.). New York: Keystone Publications.

1913 Pond’s Extract Company.

1932 Woodbury.

1934 Frances Denney Herbal Oil Blend.

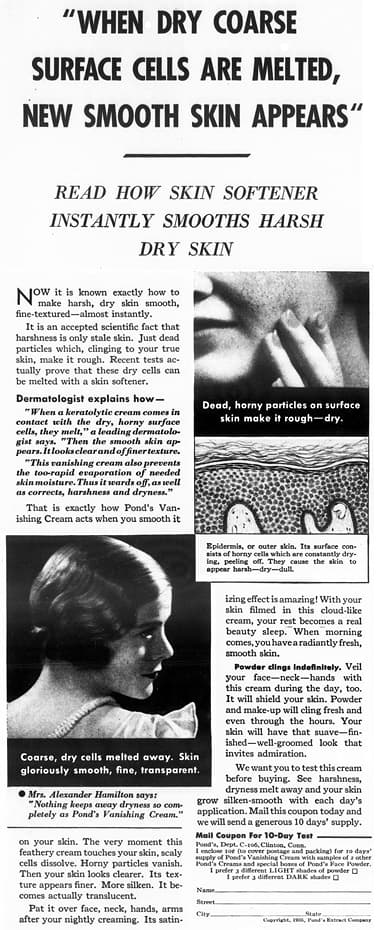

1935 Ponds Vanishing Cream claiming to act as a keratolytic that dissolved surface skin cells and removed skin roughness

1936 Daggett & Ramsdell Elorda Creams.

1938 Harriet Hubbard Ayer Luxuria Cream.

1940 Cyclax Milk of Roses for dry skin.

1940 Dorothy Gray Dry Skin Cleanser.

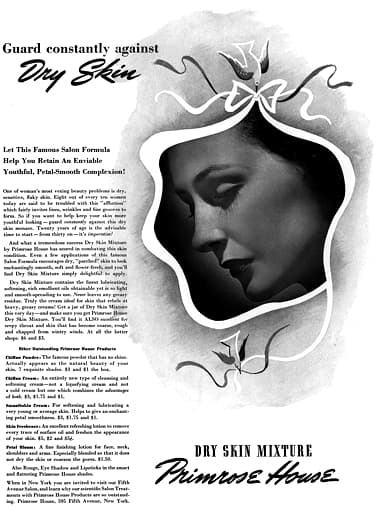

1940 Primrose House Dry Skin Mixture.

1942 Barbara Gould Velvet of Roses Dry Skin Cream.

1943 Botany Lanolin products.

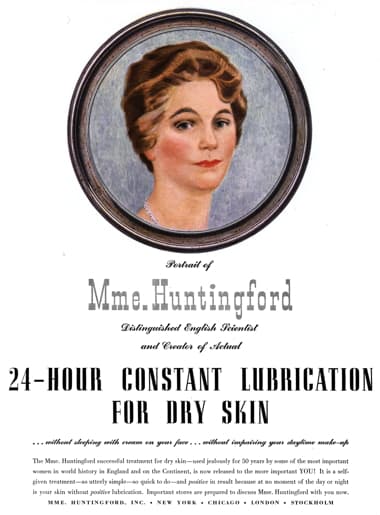

1945 Mme. Huntingford.

1954 Helena Rubinstein Vitamin-Lanolin Formula.

1955 Pond’s Dry Skin Cream.