Hystogen

In 1961, Charles Henry Willi retired from his cosmetic surgery practice, sold his London property and moved to Saint-Tropez, France, presumably to enjoy the considerable fortune he had amassed – he had over £1 million in his estate when he died (Ludovici, 1981, p. 53). What is remarkable about this story is not that Willi made a fortune from cosmetic surgery but rather that for 50 years he carried out over 15,000 surgical operations – including face lifts, nose jobs and face peels – quite legally in London without any medical qualifications whatsoever.

Qualifications

In his 1932 book, ‘The Secret of Looking Young’, Willi does list some titles after his name, namely F.C.P., F.R.S.A., and Membre de l’Academie Latine, Paris. These suggest that he was a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (F.R.S.A.) and the London College of Physiology (F.C.P.). The Royal Society of Arts and the Académie Latine were cultural, not medical organisations and Willi’s fellowship with the London College of Physiology was subsequently shown to be bogus (Ludovici, 1981, p. 35), not that the college had anything to do with the medical profession in the first place.

In 1916, Willi did receive a Doctor of Medicine from the Oriental University in Washington, D.C. but the head of the university, Helmut H. Holler, was later charged and convicted of operating a fake diploma mill (California and Western Medicine, 1926) so this qualification was also bogus. It did however get Willi into trouble. In 1921, he was prosecuted and fined in the Marylebone Police Court for passing himself off as a doctor (Ludovici, 1981), one of his very few brushes with the law.

Willi was able to operate his highly successful practice for 50 years due to a loophole in British law. The Medical Act of 1858 enabled him to practice as a plastic surgeon as long as he did not try to willfully pass himself off as a physician or surgeon. Willi was not the only person to use this legal loophole, Charles Francis Medlicott Abbot-Brown [1879-1936], for example, also offered plastic or cosmetic surgery at ‘La Maison Kosmeo’ at 37 South Molton Street, London.

Not being in the medical profession gave Willi, and others like him, certain advantages. It allowed them to advertise – something denied to the British medical profession as a whole – and enabled them to work with foreign doctors who were not yet registered to operate in Britain but were still able to do cosmetic surgery.

The major drawback was not being able to use general anaesthetics. Willi could not even hire an anaesthetist as any anaesthetist that worked with an unlicensed medical practitioner would have been deregistered. This restricted Willi to surgery that could be done with local anaesthetics with the client fully conscious. More radical cosmetic surgery requiring general anaesthetics, such as breast augmentation or reduction, was out of Willi’s reach in London. However, there is evidence that he carried out breast operations in Paris in the early 1910s as he advertised there in 1911 that he carried out ‘breast firming’ procedures.

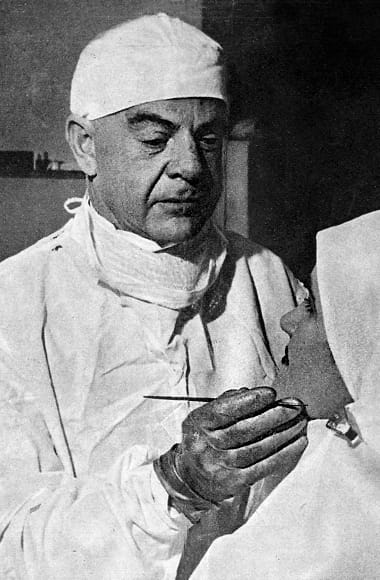

Above: 1932 Willi conducting facial surgery while the client watches in a mirror. He is using a diathermic knife (radio needle) rather than a scalpel to slice the skin.

Exactly how and where Willi developed his surgical skils is an open question but it is likely to have been through a combination of observation, reading and practice. Cameron and Wallace (1991) suggest that Willi learned to operate while working as an orderly in the operating theatre of the noted German plastic surgeon Jacques Josephs [1865-1934] between 1908 and 1909 but Willi was also the editor of ‘Disfigured Noses: And their Correction: How to Perfect Disfigured Noses by a Scientific and Successful Method’, a book released by a Dr. F. Koch in 1912. Ludovici also notes that Willi practiced his surgical procedures on animals parts such as pigs’ heads (Ludovici, 1981, p. 101).

London

Very little is known about Willi before he moved to London in November, 1910. He grew up in Lucerne, Switzerland, was fluent in French, German and English and had a number of jobs before he arrived in London, many in bookshops.

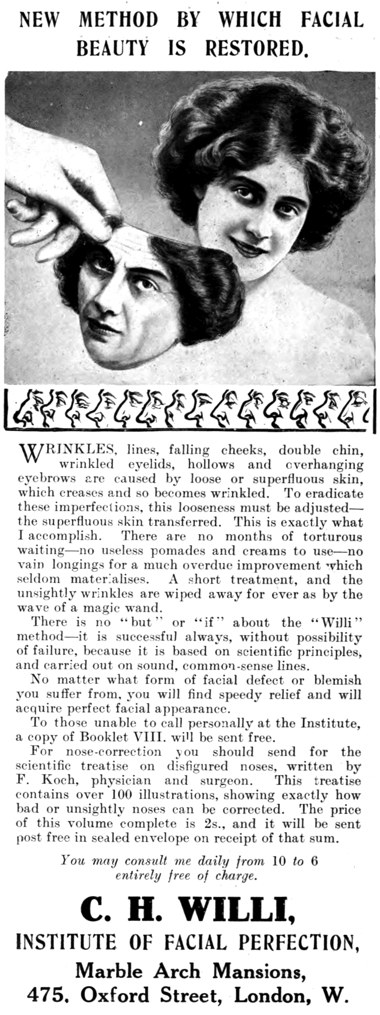

Soon after settling in London, Willi opened the ‘Institute of Facial Perfection’ at 475 Oxford Street but also ran consulting rooms in Paris at 34, Boulevard Malesherbes, where he described himself an an American specialist. It is possibile that he also operated in Hamburg and Berlin.

In 1917, he moved the London consulting rooms to 17 Baker Street – where his business was now called ‘The Hystogen Institute’ a name he stuck with until his retirement in 1961. Soon afterwards he sifted to 40 Baker Street after taking up a twenty-one year lease on the property. In 1930, he leased space at 30 Old Quebec Street and also bought a property at 26 Eton Avenue, Hampstead around this time. There he also conducted operations even though it was never advertised as a surgery. He sold the Eton Avenue property in 1962 when he moved to Saint-Tropez.

Willi advertised widely in ‘better’ magazines but also promoted his business through the publication of books such as ‘Facial Rejuvenation: The Face and its Improvement by Aesthetic Surgery’ (1926) – republished in more elaborate editions in 1949 and 1955 – and ‘The Secret of Looking Young’ (1932). Another book published by a devoted admirer Elisabeth Margetson, ‘The Living Canvas: A Romance of Aesthetic Surgery’ (1936), also brought in new clients. Willi also produced a series of booklets that potential clients could request by mail.

By the 1930s, Willi was giving interviews to major metropolitan newspapers. Rosita Forbes [1890-1967], for example, wrote a very flattering article on Willi titled ‘New Faces for Old’ for the Tatler in 1930 and, by 1950, Willi was so confident of his position that he allowed British Pathé to film him working in his surgery in Hampstead.

Above: The above link is to a short British Pathé film (1950) about Charles Willi and plastic surgery.

Hysto-Derma

Willi used a number of names over the years to describe what we was doing. Just as the ‘Institute of Facial Perfection’ became ‘The Hystogen Institute’, the ‘Hystogen Method’ was also promoted as the ‘Hystogène Method’ and the ‘Hystogen-Derma-Process’. Most of these names are derived from the Greek word ‘histos’ used in medicine as a base for words associated with tissues; e.g., histology.

Above: 1930 Dermal Histogen Institute advertisement referencing Rosita Forbes article in the Tatler.

Surgical procedures

Willi conducted surgeries to correct a number of ‘facial imperfections’ including:

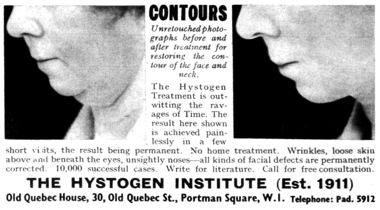

Restoring the facial contour.

Restoring the contour of the neck.

Correction of double chins.

Correction of baggy chin, receding and protruding.

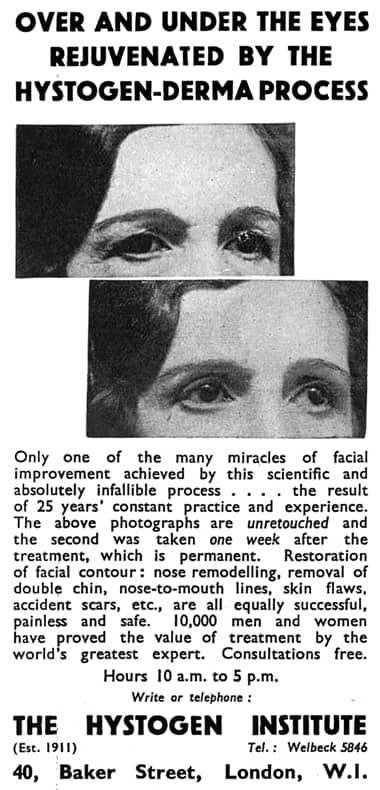

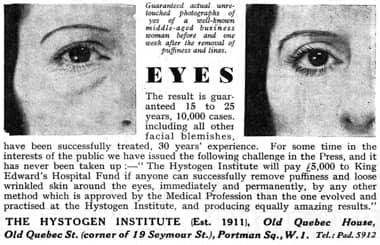

Removal of loose skin under the eyes.

Removal of pouches from above the eyes.

Removal of frown lines.

Removal of naso-labial lines.

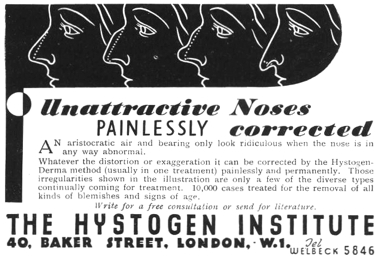

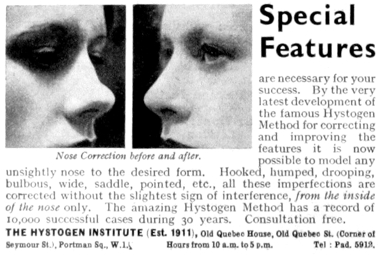

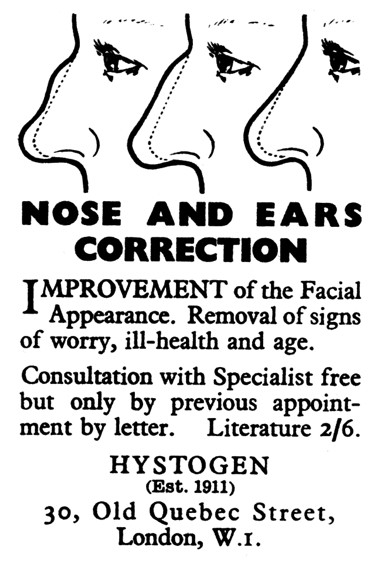

Correction of unsightly noses—viz., too long, hooked—too thick—turned up—large nostrils, etc., etc.

Correction of ears—viz., outstanding—too large—deformed.

Correction of lips—viz., too thick—badly shaped.

Removal of scars, birthmarks, moles, warts, red veins, cysts, growths, etc., etc.(Willi, 1932, p. 11)

Despite his lack of formal training, or perhaps because of it, Willi used a number of techniques that were considered very advanced for their time. For example: his rhinoplasty was done from the inside of the nose so that it did not leave scars (a procedure developed by the German plastic surgeon Jacques Josephs [1865-1934]); his bone removal was done with a dynamically-operated chisel rather than a conventional saw; he used a diathermic knife (radio needle) instead of a scapel so that wounds did not bleed as he cut (bloodless cautery); he used leeches to clear haematomas (a procedure that has been recently resurrected); and he filled lines and furrows using the patient’s own fat transferred using a syringe (if he did not invent this procedure then he was certainly one of its earliest exponents).

Above: 1932 Willi reshaping a nose from the inside. He is using a magnifying lens he personally developed.

Above: Willi injecting fat into the naso-labial fold. He first mentions this procedure in 1926.

See also: Diathermy

Undoubtedly Willi developed some of these techniques in part because his patients remained conscious during his operations. Diathermy enabled him to claim that he was able to ‘eliminate the knife’ and the general absence of a scalpel and visible bleeding during the operation would have been reassuring to his fully awake clients.

The greatest obstacle to be encountered from the Public in my experience, is the inborn fear of the word “Surgery.” This seems immediately to suggest terrifying thoughts of anæsthetics and the knife, of blood-shedding and pain, of poisoning and scars. With the present development of surgical technique such fears are absolutely groundless, and I wish to emphasise that scarless æsthetic surgery, when performed by an expert, is no mere euphuistic phrase, but a well proven fact.

(Willi, 1932, pp. 7-8)

Willi was described as being incredibly quick by those members of the medical profession who observed him performing. Elisabeth Margetson provides us with some idea of this in her descriptions of Willi’s operations. A paraphrased version of one is given below:

Its prelude is a glass of sal volatile … which, together with the calm, commonsense atmosphere created by surgeon and staff, allays the disquiet of a long, long night before. The conditions of the operation are as aseptic as Willi promised. An assistant lathers Mrs Margetson’s temples which she then shaves. One side of the face chills as Willi sprays ethyl chloride. A faint prick. Willi has injected novocaine. He sustains a running commentary. The known is less fearful. The unknown most fearful. Buzzing. An assistant holds up to Mrs Margretson’s eyes a long tube stretched out from a machine. The tube ends in a fountain pen-like device from which projects a hair-thin needle. A radio needle. Cauterises as it cuts. No bloodshed. The radio needle has made possible impossibly delicate brain surgery.

Willi was lightening. Swift as a Mississippi card sharper. And sure. Patients, assistants, always testified to his swiftness and sureness. done in a quarter of an hours, one eye. Five minute break. Done in another quarter of an hour. Mrs Margretson’s second eye. Half and hour, both eyes. More novocaine, this time round the nostrils. Willi injects face extracted from beneath the eyes to puff out and smooth the nose-to-mouth lines. More ethyl chloride. More novocaine. Buzzing again. Willi moulds, manipulates, presses, irons with his strong hands. Haute couture, only the material is living tissue. Half an hour a new face. One hour and five minutes new everything.

Living canvas.

Three days’ bed rest to aid healing, towards nervous revival. Stitches out, painlessly by Titanium ray, which, trained on the incisions, ‘fades’ scars away. Daily doses of Titanium ray which in a week expose a skin as fresh as a baby’s or an old-time milkmaid’s.(Ludovici, 1981, pp. 90-91)

Vulnerabilities

Very few of Willi’s operations ended up in court. The most important case brought against him was by Miss Christian Clara Vernon, who worked for him from 1922 to 1926. The case concerned a breach of contract (wrongful dismissal) that Vernon felt was the result of eye surgery that Willi had done on her which had gone wrong. The case set Willi back £30 and his own legal costs but more importantly it highlighted his legal vulnerability – another disadvantage of not being a member of the medical profession.

To help protect himself from future legal claims Willi made all subsequent clients sign a document of absolution declaring that they were taking surgery at their own risk (Ludovici, 1981, p. 75). Willi had registered Hystogen as a limited liability company (Hystogen Institute Ltd.) in 1925 with a capital of £500, presumably to limit legal access to his personal fortune but, for reasons unknown, had put the company into voluntary liquidation in 1929, so he may not have been too concerned about litigation.

Not that much of Willi’s amassed wealth was in Britain; many clients paid in cash and Willi ‘repatriated’ much of this off-shore on his trips to Switzerland where it was beyond the reach of British taxation or legal redress.

Willi also protected himself by including European medical professionals in his practice, even though they were not registered to practice in Britain. Starting with Dr. John Bell (a dentist) these included Dr. Zaranska, Dr. Westmann, Dr. Bankoff, Dr. Hellman, and Dr. Brewda.

Having said this, I note that few clients seemed dissatisfied with Willi’s treatments and he probably had no more problems than any medical practitioner working in a similar area. Besides, unlike Americans, the British were not particularly litigious.

Beauty salon

Willi viewed traditional beauty treatments as extremely limited in their ability to produce results.

No amount of massage, slapping, kneading, rolling, exercises, foam and mud baths, appliances, creams, lotions, pomades and other applications, nor the use of any other apparatus in existence can ever restore to the face its pristine beauty or relieve a sufferer from a facial blemish.

Neither can the grafting of glands nor the injection of their secretions into the bloodstream with all their beneficiary qualities of health, permanently affect the structure and the features of the face(Willi, 1932, pp. 39-40)

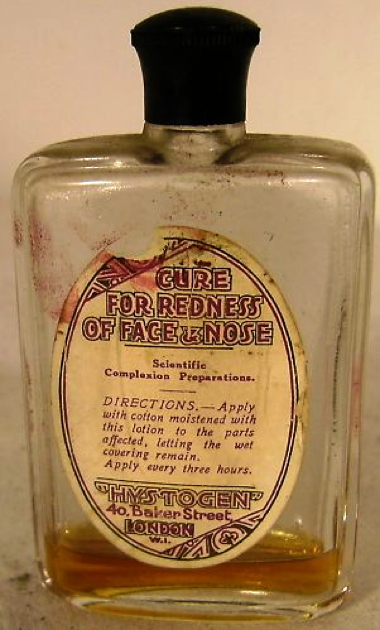

This did not stop him from opening the Valmont Beauty Institute in Baker Street (Ludovici, 1981, p. 57). However, lack of support and probably lack of continued interest on Willi’s part, saw it close within a short period of time. It would appear that Willi did manufacture some products under the Hystogen name but only one – a treatment for couperose – has come to light so far.

First Posted: 30th December 2013

Last Update: 22nd October 2023

Sources

Cameron, K. M., & Wallace, A. F. (1991). “Dr. Willi” (1882?-1972?), disciple of Jacques Joseph. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 88(2), 363-364.

Forbes, R. (1930). New faces for old. The Tatler. February 26, iii.

Ludovici, L. J. (1981). Cosmetic scalpel: The life of Charles Willi, beauty-surgeon. Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire: Moonraker Press.

Margetson, E. (1936). Living canvas: A romance of aesthetic surgery. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

Taschen, A. (Ed.). (2005). Aesthetic surgery. Italy: Taschen GmbH.

Willi, C. H. (1932). Secret of looking young, with the aid of the hystogen-derma-process: Based on 10,000 successful cases & twenty-five years’ experience. London: Cecil Palmer.

Karl Heinrich Willi also known as Charles Henri Willi and Charles Henry Willi [1883-1972]. The photograph was taken in 1926 by Walter Bird.

1911 C. H. Willi, Spécialiste american du visage. In this French advertisement Willi describes himself as an American specialist with offices in Hamburg and Berlin. The French consultation rooms are at 34, Boulevard Malesherbes, Paris.

1912 The Institute for Facial Perfection.

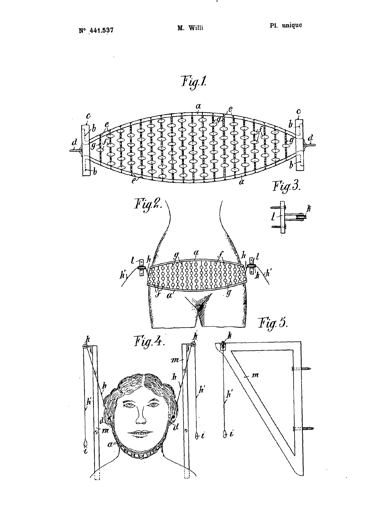

1912 Drawing (done by Marie Willi, his wife) from a patent for a chin strap taken out by Willi (No. 441,537). Willi was very interested in health cults and dieting and sold cures for obesity in the early part of his career.

1913 The Institute for Facial Perfection.

1918 The Hystogen Institute. The image suggests that you pull the skin of the face back to see the benefits of facial surgery. The foundation date of 1907 is impossible given that Willi only arrived in London in 1910. I presume it was used to suggest to potential clients that the institute had been around for some time. Willi also uses Dr. in this advertisement, something he avoided after 1921 when he was fined for placing the initials M.D. after his name.

1925 Hystogène. The foundation date of the institute is now given as 1910 which is closer to the truth.

Rosita Forbes, née Joan Rosita Torr [1890-1967] was a well-known English travel writer and explorer. Her article about Willi in the Tatler must have drummed up a lot of business in the 1930s.

1934 The Hystogen Institute.

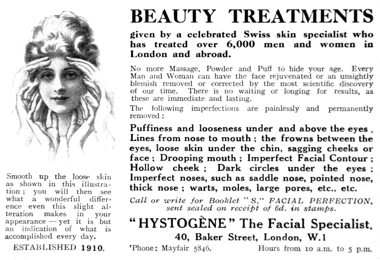

The Hystogen Cure for Redness of Face & Nose.

1936 The Hystogen Institute.

1938 The Hystogen Institute. The foundation date is now listed as 1911 which would be the year that Willi started practicing surgery in London.

1938 The Hystogen Institute puff eye treatment.

1939 The Hystogen Institute contour treatment.

1944 The Hystogen Institute.

1952 Willi studying a patient’s face.

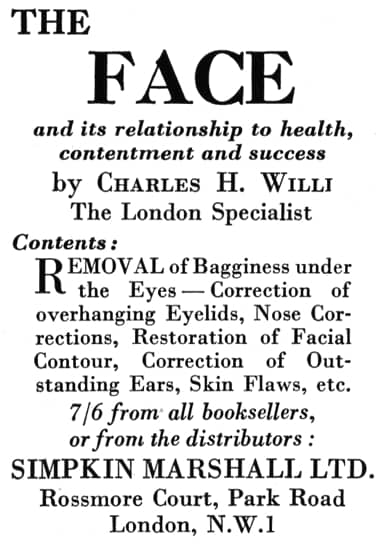

1952 Advertisement for ‘The face and its relationship to health, contentment and success’ by Charles H. Willi, The London Specialist. This may be a reprint of an earlier book under a revised title.