Yardley

Continue to: Yardley (post 1945)

Although 1770 is given as the foundation date for the House of Yardley, the firm was actually established by Samuel Cleaver [c.1750-1805] and it would be a new century before the Yardley family became involved in the business. The Yardley and Cleaver families were connected through marriage, with two of Samuel Cleaver’s sons marrying daughters of William Yardley [c.1756-1824] – William Cleaver married Hermina Yardley in 1801 and Edward Cleaver married Rosina Yardley in 1808.

When Samuel Cleaver died in 1805, he left the business to his wife and four sons who traded as the Cleaver Brothers. Exactly how the business ended up in William Yardley’s hands is not clear. Thomas suggests that William Yardley had provided surety for a £20,000 loan that his son-in-law, William Cleaver, had taken from Coutts bank and had acquired the business in 1823 when the debt could not be repaid (Thomas, 1953). Even if true, this cannot be the whole story.

Bankruptcy notices issued against the four brothers indicate that the business had slipped into insolvency as early as 1813. However, William Cleaver was declared bankrupt again in 1823 while trading under the name of William Cleaver and Company, so it is possible that William Yardley provided surety for his son-in-law to buy his brothers and mother out, and when the business finally collapsed he gained control in return for paying his son-in-law’s debts as Thomas suggested.

Yardley and Statham

William Yardley died in 1824, one year after acquiring the Cleaver soap and perfume business. He left the company to his son Charles Yardley [c.1795-1882] who then got his cousin Frederick Cleaver to manage it. When Frederick resigned in 1841 to start his own perfume and soap business – F. S. Cleaver & Sons – Charles partnered with William Statham [1809-1863] who ran the firm then renamed as Yardley and Statham. Describing itself as a manufacturer of superior toilet soaps and choice perfumery, Yardley and Statham had offices at 7 Vine Street, Bloomsbury, London and at 5 Rue des Vieilles, Haudriettes, Paris. They sold a variety of products for men and women including soaps, perfumes, toilet waters, toiletries, face powders and pomades for the hair.

Sun Flower Oil Soap: renders the skin beautifully soft, white, and pliant, and emits a refreshing and exquisite odour; it is acknowledged to be the Perfection of Toilet Soaps.

Honey Soap: invented by them in the year 1845, continues to command the most undeniable appreciation by the public.

Cold Cream Soap: prepared expressly for Ladies and Infants, is perfumed with Otto of Roses, and has been justly ranked as the most efficient, yet harmless improver of the complexion.(Yardley and Statham advertisement, 1862)

Yardley and Statham traded domestically through chemists and dealers in perfumes and shipped goods aboard to British dominions like Australia, as well as to the United States and Europe.

Yardley & Company

After William Statham’s death in 1863, the firm passed into the hands of Charles Yardley’s son, Charles Yardley junior [1824-1872], who died before his father. Charles Yardley junior’s son, Robert Blake Yardley, was too young to run the business so it was put in the capable hands of Thomas Gardner, who became its manager and later a partner in the business. In 1890, Gardner converted Yardley into a joint stock company (Yardley & Co. Ltd.) and became its first chairman. Notification of the new joint stock company indicates that the business was previously carried on by Mary Anne Sophia Yardley and Thomas Exton Gardner at Ridgmount Street, St. Pancreas (‘The Chemist and Druggist’, August 9, 1890).

Poor management saw the company’s fortunes decline after Thomas’ death in 1891 and it would not be until his two sons, Thornton and Richard, joined the firm that its fortunes would rise once again. Thornton joined the company in 1890, became a director in 1897 and the managing director in 1900; Richard joined the company in 1900 and became its secretary in 1905 (Thomas, 1953).

A new century

The situation the brothers faced in 1900 was very different to that of their father. Prime Minister Gladstone’s removal of the tax on soap in 1853 had made soap cheaper. This stimulated increased production but the entrance of new soap manufacturers, like the Lever Brothers, increased competition. Scientific developments, particularly in the production of caustic soda, were also moving soap production from a cottage industry into full-scale industrialisation. The long-term effect of all this was that the soap industry entered into a period of consolidation in which large companies would dominate the trade.

Wisely, the brothers decided to develop the perfume and toiletries side of the business and, by the beginning of the First World War, Yardley was producing an expanded range of toilet requisites that included perfumes, toilet waters, soaps, face powders, toothpastes, brilliantines and shaving sticks.

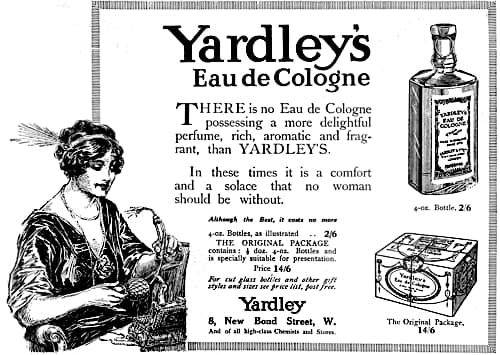

Above: 1916 Yardley Eau de Cologne.

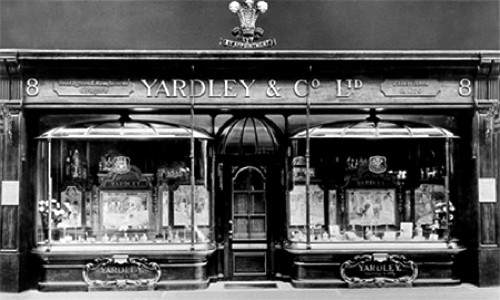

A decision was also made to move from wholesale to retail. This meant that the Yardley brand needed to be strengthened. A retail store was opened at 8 New Bond Street, London in 1910 and overseas depots were established, beginning in 1905 with an office in Pitt Street, Sydney, Australia. These depots would eventually become subsidiary companies in the 1930s.

Above: Yardley’s Georgian style retail store at 8 New Bond Street, first opened in 1910. Yardley maintained wholesale sales offices and showrooms in the upper floors of the building. This photograph must have been taken after the Prince of Wales (later the Duke of Windsor) issued a Royal Warrant for Yardley soaps in 1921 as his crest appears above the shop.

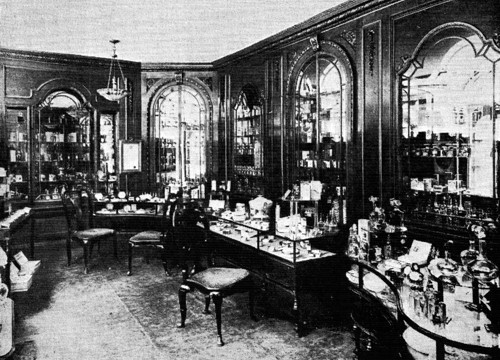

Above: Interior of the New Bond Street retail store.

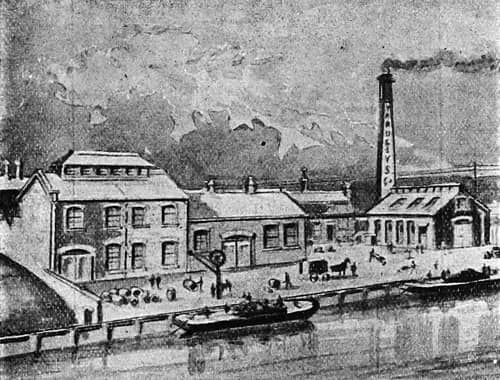

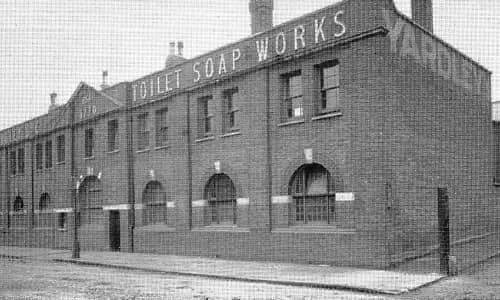

The company’s manufacturing base was expanded to meet the increasing demand. A three-story factory had been situated in Vine Street, London from before 1855 and the company had moved to a new and larger factory in Ridgmount Street, Bloomsbury in 1883. This was now inadequate so the company took out a 100-year lease from the Carpenters Company and built a larger factory at Carpenters Road, Stratford in 1904.

Above: 1904 Engraving of the Yardley factory in Carpenters Road, Stratford bordering on a canal giving the factory access to a transportation system. Electricity for lighting and power was generated on the premises. A horse van can be seen in the drawing.

In 1918, additional land next to the factory was acquired and a building was leased in High Street, Bow for a bonded warehouse used to manufacture and store perfumes for export.

Above: 1920 Yardley soap factory at Carpenters Road.

Above: 1925 Yardley factory at Carpenters Road (Historic England). Motorised vans were used for the first time in 1924 and in the use of horse vans was discontinued the following year.

Above: c.1920 Making powder compacts at Carpenters Road (Historic England).

Above: c.1920 Packing Department at Carpenters Road (Historic England).

In 1926, a three-story block was completed and, in 1931, a second three-story block was added. A new box-making factory was established in High Street, Stratford in 1937, commencing production in 1938.

Above: 1937 The newly built Yardley box factory, Warton House, High Street, Stratford designed by Higgins & Thomerson.

Above: A recent photo of the Yardley box factory taken from the other end with the flower-sellers emblem visible. By this time it was no longer used by Yardley and the box factory sign has been removed.

Both properties were damaged during the war but the company had moved much of its stock and reserves to a site at Boreham Wood where it was stored until the building was requisitioned.

Lavender

Apart from the period encompassing the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars – when French ports were blockaded and the distribution of French perfumes was restricted – France dominated world perfume markets through to 1914. The only exception was lavender which – along with rose and violet – was one of the most popular scents in Victorian times. As well as being used in soaps, perfumes and toilet waters, lavender was used in potpourris, to scent clothing and linen, and as a cure-all.

English lavender was generally regarded as superior to French and it commanded a higher price. As well as differences in the types of plants grown, English lavender came from the flowers of cultivated plants, whereas French lavender of the time was sourced mainly from wild plants and often included stems and leaves along with the flowers.

Above: 1920 Yardley Old English Lavender Water and Soap.

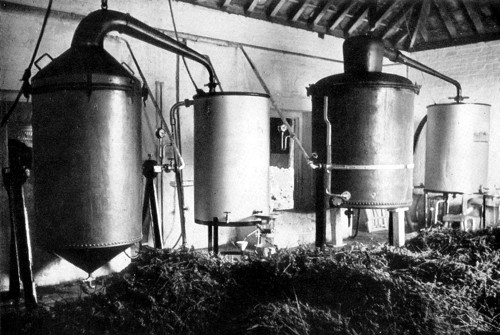

Although Yardley promoted English lavender in its advertising, much of the lavender it used, particularly in its cheaper lines, was French. Price was not the only factor. The traditional English lavender growing regions in Surrey and Lincolnshire were in decline, mainly because of the expansion of greater London. Fortunately, in the 1930s, a new lavender growing area was established in Norfolk and Yardley built a distillery there to extract it.

Above: Hand picking English lavender at Fring, Norfolk (Poucher, 1932).

Above: The Yardley distillery at Fring, Norfolk (Poucher, 1932).

The use of French lavender in Yardley products appears to have ceased sometime after the Second World War. John H. Seager – Yardley’s chief chemist and later technical controller – was sent overseas to source different species and cultivars of lavender. From these Yardley developed its own cultivar of Lavandula angustifolia which was grown in England and used exclusively in all their lavender products after the war.

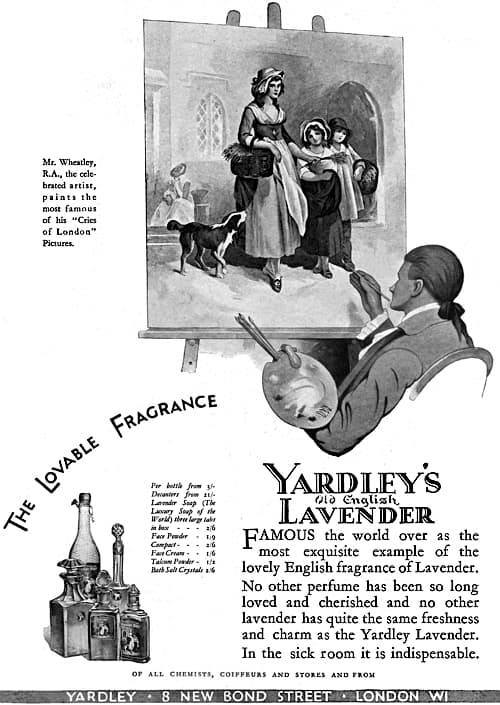

In 1913, Yardley purchased an engraving of Francis Wheatley’s ‘The Flower-sellers’ – part of his ‘Itinerant Traders of London’ series of paintings. Despite the fact that the painting depicted the sale of primroses not lavender, it was used to promote Yardley’s ‘Olde English Lavender Soap’ and other lavender-based products for many years to come. The company also produced porcelain versions of the flower-seller for use in advertising displays; these are are now highly collectable.

Above: 1928 Yardley Old English Lavender.

Yardley & Company Ltd.

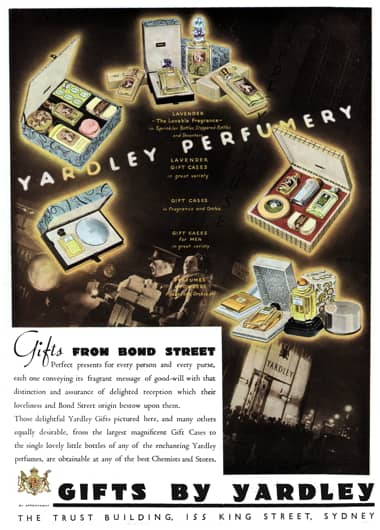

Although the Yardley brand was well established in the British dominions, it was less well known elsewhere. Steps to rectify this were taken after Yardley become a Public Limited Liability Company in 1920. An American subsidiary was established in 1921, with an office at 15 Thirty-Sixth Street, New York, then moved to larger premises in Madison Square in 1923. New York showrooms were also opened at 452 Fifth Avenue but these were relocated to the British Empire Building in the Rockefeller Center in 1933.

Above: British Empire Building (front left) in the Rockefeller Center.

Branches were also established in other American cities including Chicago (1928), San Francisco (1928) and New Orleans (1934), the later transferred to Dallas, Texas in 1937. Local American manufacturing appears to have begun after the establishment of Yardley & Co. Ltd. in Union City, New Jersey.

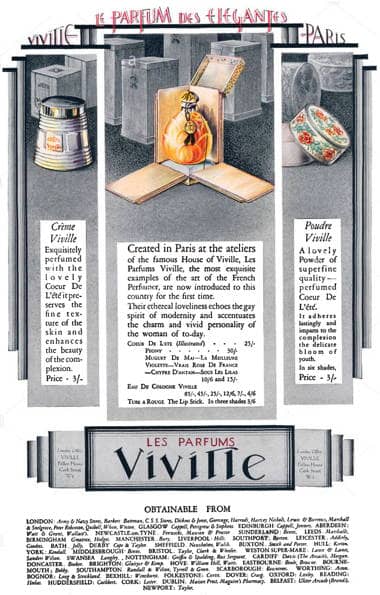

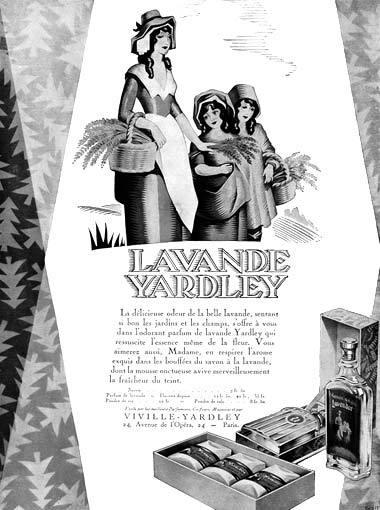

In 1924, Yardley purchased the French perfumery Viville (established 1892) with its main office at 24 Avenue de l’Opera, Paris and factory in the suburb of Courbevoie. The Avenue de l’Opera shop was redecorated by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann [1879-1933] and Yvonne Brunet was engaged to redesign Viville packaging. By 1937 the showrooms and offices had moved to a more fashionable position at 279 Rue St. Honoré. Operating as Viville-Yardley – until it became Yardley et Cie – it was used to promote Yardley products throughout France and Europe.

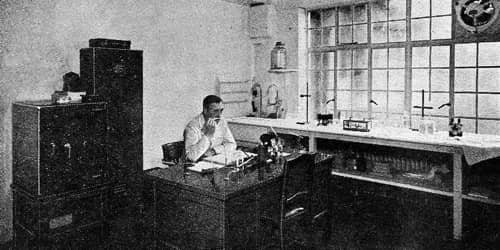

Above: The interior of a Yardley laboratory, date unknown. Although I am uncertain as to its origins, this photograph may have been taken in a Viville laboratory.

The Commonwealth nations were not forgotten and subsidiary companies were set up in Toronto, Canada (1935) and Sydney, Australia (1939). As these Yardley subsidiaries developed, they set up factories to make or assemble Yardley products. This increased production, saved on transportation costs and enabled Yardley to avoid local import duties.

In 1927, Yardley needed more space than was available in the upper floors of New Bond Street so new premises were leased nearby at 7 Pollen House, 10 Cork Street. Subsequently, a perfume laboratory and art studio were also established there. By 1933, the continual growth of the company necessitated another move, this time to Sackville House in 40 Piccadilly, Mayfair. The company moved its retail showrooms, offices, laboratory, art studio, and advertising department into this building and it became the management and wholesale sales centre for the company.

Above: 1934 Yardley wholesale showroom in Sackville House designed by Reco Capey, with furniture by Gordon Russell Ltd.

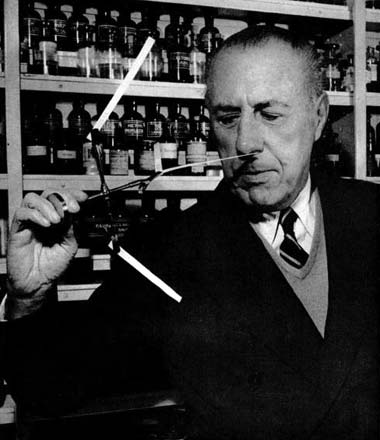

Above: 1934 W. A. Poucher in the laboratory in Sackville House.

When the lease ran out on the building at 8 New Bond Street Yardley moved its retail shop to the ground floor of Yardley House at 33 Old Bond Street, a new building the company had constructed In 1931. Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann was once again engaged in the design of the shop.

Above: Yardley House, 33 Old Bond Street. Architects were Wimperis, Simpson & Guthrie. The frieze of floral decorations on the top of the building was designed by Reco Capey. In 1927, Yardley would buy the building to the right in Old Bond Street and use it to create a beauty salon. Most of the building was leased to the fashion house Corot of Bond Street until Yardley moved most of its administration, the perfume laboratory, art studio, advertising department and showrooms into the building in 1946.

Above: A closer view of the retail shop in Yardley House. The door and other elements were designed by Reco Capey.

By the late 1930s Yardley was thriving. British regulation changes that enabled Yardley to switch to using duty-free industrial spirits as a solvent, allowed the company to reduce the prices of many of its lavender lines, thereby boosting sales. Demand for Yardley products was also helped by Queen Mary issuing a second Royal Warrant for Yardley perfumes (1932). A previous Royal Warrant had been issued in 1921 by Edward, Prince of Wales, for perfumes and soap. Unfortunately, this streak of good fortune was interrupted by the outbreak of war in 1939.

Above: 1934 Assorted Yardley products.

As well as the Gardner brothers, some of the company’s success during the interwar period can be attributed to the work of William A. Poucher and Reco Capey.

William Poucher

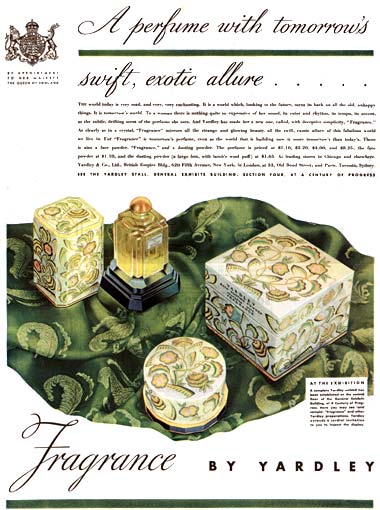

W. A. Poucher worked as a consulting perfumer-chemist for Yardley from 1927, joining the firm in 1929 after disposing of his consulting practice. His appointment as a perfumer was a bold move at the time, as he was English not French, but he had solved an important cosmetic problem for Yardley in 1929 (Bouillette, 1955) – which I assume to be associated with the formulation of English Complexion Cream released in that year – which impressed the Yardley board. He produced a range of new fragrances for Yardley including Freesia, Orchis and Bond Street and also worked on the formulation of numerous products in the Yardley range.

Reco Capey

Reco Capey was engaged by Yardley as its Art Director in 1928 and was later assisted by Katharine Bertram Stone. The couple were married in 1935 and they went to New York together in 1940 for the duration of the war. During Capey’s time as Art Director, Yardley’s elegant cosmetic containers with flower and honeybee motifs were designed. Manufactured by Beetle Products Co. Ltd., they made Yardley products very distinctive in the 1930s and 1940s. Reco Capey was also placed in charge of other areas of design including advertising artwork as well as store fittings and fixtures.

Products

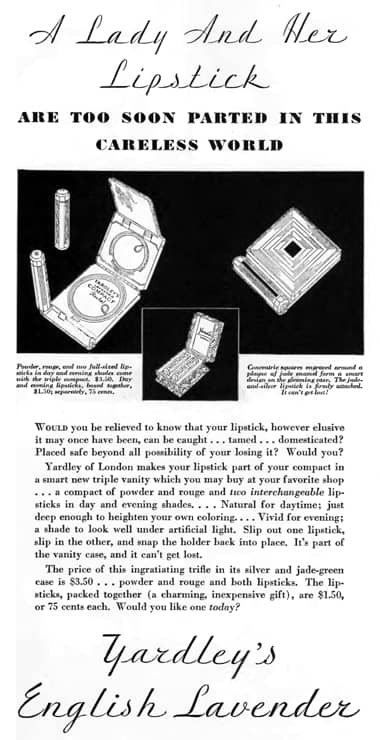

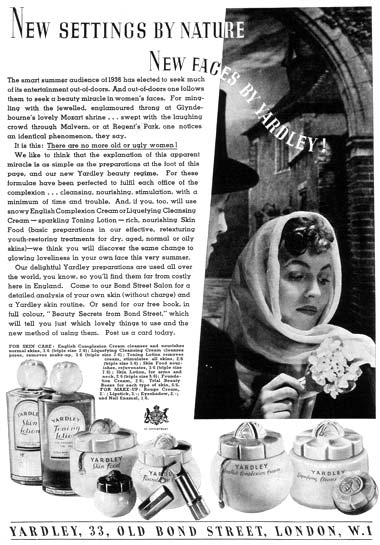

Yardley had been making an assortment of beauty products for some time, including Lavender Cold Cream, Lavender Vanishing Cream, lipsticks and powder compacts. Although it continued to promote its soaps, perfumes and toiletries – many of which were based on English Lavender – in 1929, it began to expand and update its beauty lines.

Beginning with the introduction of English Complexion Cream in 1929, Yardley developed a comprehensive line of beauty products and organised them into a system of beauty care. In 1935, the company hired Mrs. Olive Cato to take charge of this area and began opening salons where beauty treatments using Yardley products could be carried out. In 1937, the property adjacent to Yardley house on Old Bond Street became available and the company purchased it and opened a beauty salon it in (Thomas, 1953). Yardley wisely used its lavender-based soaps as their ‘foundation for beauty’ but combined them with other products to promote the idea of an ‘English complexion’.

Natural, young and lovely … an English Complexion.

Skin petal-soft, lips alive with color … an “English Complexion” is naturally, delightfully charming. To make its attractions yours, There’s the simple beauty routine of fashionable women the world around—daily care with Yardley Aids to Beauty.(Yardley advertisement, 1948)

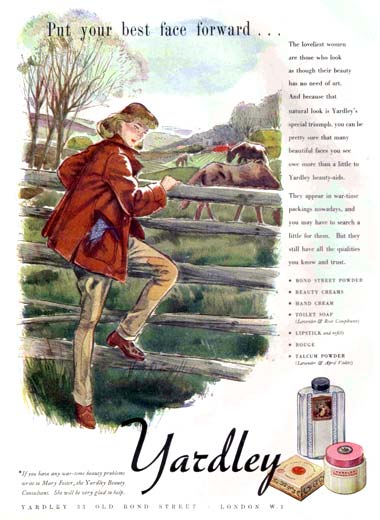

Initially, ‘English Complexion’ meant the complexion of English socialites and the aristocracy but by the 1940s the egalitarian effects of the war saw this morph into something more generalised.

An English complexion

The Yardley English Complexion beauty system of the early 1930s was a 3-step routine of cleanse, tone, and apply powder foundation – even though the company did not have a well-defined toner and used Lavender Water in its place. English Complexion Cream was used as a secondary cleanser and a powder foundation, and also acted as a ‘skin food’ when used overnight.

To begin, there is Yardley’s English Lavender Soap for shampooing the face and neck. Its cooling fragrance is a revelation. It is followed by Yardley’s English Complexion Cream to complete the cleansing, to dislodge the impurities which seem to elude even the most penetrating lather. The cream is removed with a cotton pad saturated with lavender lotion or your own special astringent. Now your skin is ready for the second coating of English Complexion Cream, which remains on all night to soften and nourish the tissues.

In the morning, this same cream becomes your powder foundation. Let your skin absorb as much of it as it will; then wipe away the surplus with water and an ordinary wash cloth, or with cotton and tonic, or simply with tissues. Yardley’s English Lavender Face Powder will cling perfectly to the fine invisible film that remains.(Yardley advertisement, 1930)

Also see the company booklet: A beauty secret from across the sea

Given that Yardley did not establish a beauty salon until 1937, it is interesting to ponder the origins of its ideas on skin-care. Although it is true that the Yardley system of beauty care was not out of step with practices of the time, many of its ideas may have come from W. A. Poucher. In 1926, before he began consulting for Yardley, he had published the book ‘Eve’s Beauty Secrets’, which he thought would “be of some assistance to women desiring to retain their beauty by means of the substances placed at their disposal by modern science” (Poucher, 1926). This is the only case I know of where an industrial chemist has put pen to paper in this way. Most of the ingredients described in Yardley’s skin-care routine are there, soap and water, cleansing cream, skin foods and facial massage.

While it is impossible for any woman to lead a placid and uninteresting life free from all cares, yet it is within the power of all to spend five minutes each day upon a treatment that will, at any rate, retard the appearance of wrinkles, and materially assist nature in maintaining that roundness and firmness of the face so typical of radiant youth.

(Poucher, 1926, p. 25)

Olive Cato probably read Poucher’s 1926 book ‘Eve’s beauty secrets’ and, given that Poucher played a role in many of the new skin-care products developed in the 1930s, it seems likely that he also had a hand in the development of Yardley’s skin-care system.

Above: 1935 Yardley display stand for Beauty Secrets from Bond Street.

Skin types

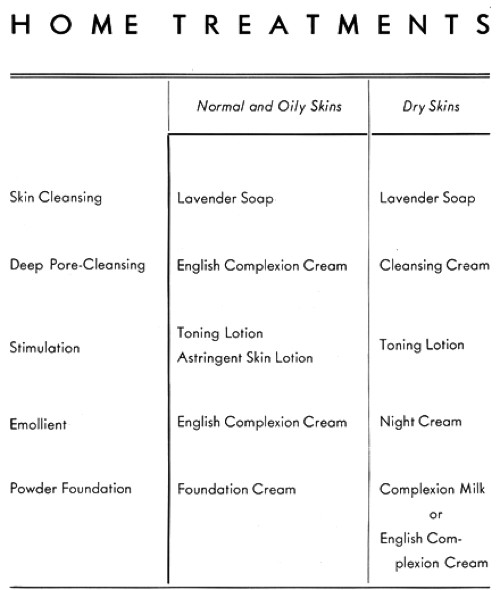

Additional skin-care products added in the 1930s enabled Yardley’s routine to be customised for dry, normal and oily skins. For example, the use of Lavender Water as a general toner was replaced with Yardley Toning Lotion for dry and normal skins and Yardley Skin Astringent Lotion for oily skins. There was also a greater range of powder foundations with the addition of Foundation Cream and Complexion Milk.

Lavender soap: “[Y]our first weapon in the battle to keep your beauty”.

Liquefying Cleansing Cream: “[S]eems to penetrate the dry parched condition and actually soften and remove the little flakes of surface matter”.

Toning Lotion: “[R]emoves cream, stimulates all skins”.

Astringent Skin lotion: “[F]or that imperative refining and stimulation of the pores”.

Skin Lotion: “[F]or arms and neck”.

Complexion Milk: “[A] skin lotion that also soothes and smooths … insures a day-long, smooth-as-silk finish to your powder”.

Skin Food: “[N]ourishes, rejuvenates”.

Night Cream: “[R]ich in beneficial oils that will actually retexture the skin while you sleep”.

Foundation Cream: “[Y]our powder base”.

Like another British cosmetics company, Cyclax, some preparations had multiple uses. This meant that their purpose was not self explanatory which could create some confusion in the mind of the user. English Complexion Cream was the worst offender, being listed as a cleanser and emollient on normal and oily skins, and a powder foundation on dry skins.

Above: 1937 Skin-care chart from ‘Beauty Secrets from Bond Street’.

Also see the company booklet: Beauty Secrets from Bond Street

Make-up

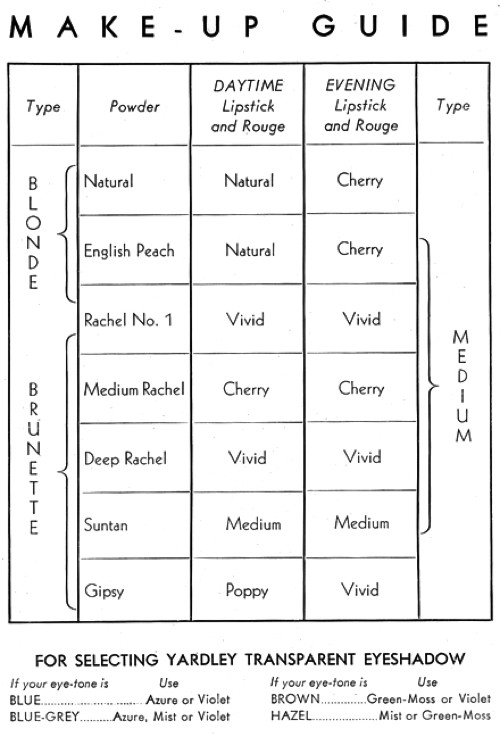

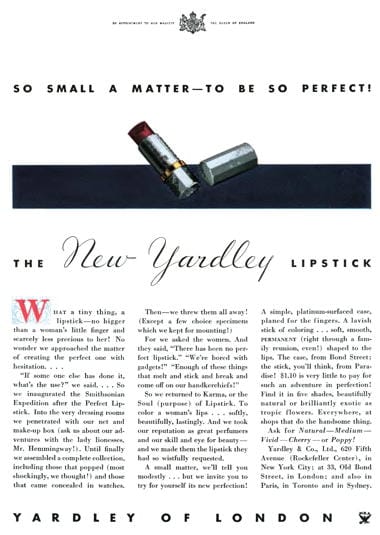

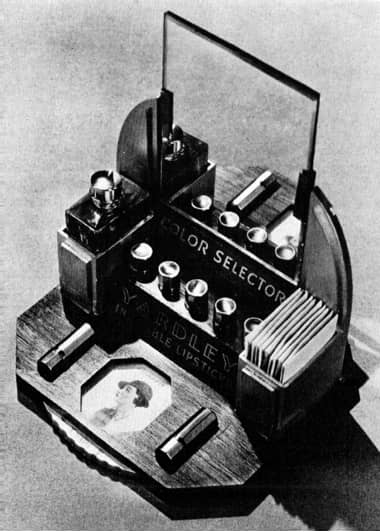

The company also extended its range of make-up in the 1930s with new lipsticks, powders and eyeshadows in matching shades along with a very limited number of nail enamels. Shade names used established terms or names taken from nature.

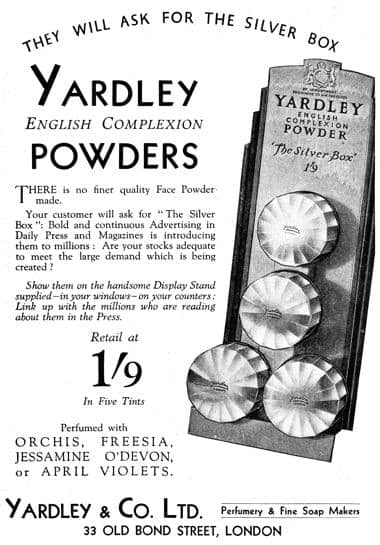

English Complexion Powder: Available in specialized boxes depending on the perfume used i.e., Lavender, Bond Street, Orchis, Lotus, Jessamine or Fragrance. Shades: Natural, Rachel No. 1, Medium Rachel, Deep Rachel, Suntan (Rose Rachel), English Peach and Gipsy.

Rouge: Rouge Compact and Cream Rouge. Shades: Natural, Medium, Vivid, Cherry, and Poppy.

Lipstick: Shades: Natural, Medium, Vivid, Cherry, and Poppy.

Eye Shadow: Shades: Azure, Mist, Green-moss and Violet.

Nail Enamel: Shades: Natural (flesh pink) and Ruby.

Advice was available for clients that enabled them to match colours with their skin tone.

Above: 1937 Make-up chart from ‘Beauty Secrets from Bond Street’.

Other products included soaps, perfumes, toilet waters, dusting powders, bath salts, hair preparations, hand lotions and shaving creams. As far as I can tell Yardley did not make a mascara at this time.

Men’s lines

Due to the English dominance in men’s tailoring – based largely in Savile Row, London – men’s toiletries, along with soaps and lavender products, were a traditional strength of the English perfume and toiletries industry. Paris may have been the centre for female fashion but the well-to-do male went to London to buy a suit.

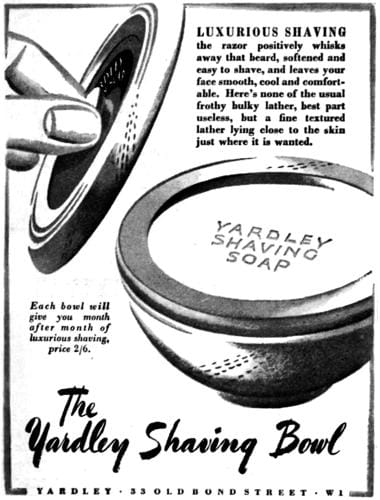

Yardley had been selling men’s toiletries for centuries with a range that included pomades, colognes, talcs, brilliantines and shaving soaps. Popular products from the 1930s and 1940s included a wooden shaving bowl (with included Shaving Soap), Hair Tonic, Invisible Talc (used as an after-shave) and After Shaving Lotion.

Second World War

Like other British cosmetic companies, the Second World War hit Yardley harder than its American counterparts. European supplies and markets were severed, factories were requisitioned, production restricted and assets bombed. In 1942, two floors at Carpenters road were requisitioned for the manufacture of aircraft parts and sea-water purification tablets while the box factory turned out aircraft flare tubes ans anti-radar devices. Thornton Gardner, at the request of the company director was relocated to New York as were some staff such as Reco Capey and Katharine Stone. The 1940 Board of Trade Concentration of Industries Order also meant that Yardley was manufacturing cosmetics for a number of other companies on its premises including Morny and Zenobia (Thomas, 1953).

In the United States, Yardley dropped its in-store demonstrators as a wartime measure in 1943, becoming the first large cosmetic house to do so. The company also reduced the shade range of its make-up lines. However, there were some new products such as a new hand cream (released in the U.S.A. in 1943) that had been originally created in England for women working in factories as part of the war effort.

Timeline

| 1770 | Samuel Cleaver establishes the soap and perfumery business that will eventually become Yardley. |

| 1823 | William Yardley gains control of the Cleaver soap and perfumery business. |

| 1841 | Charles Yardley takes on William Statham as a partner to form Yardley and Statham. |

| 1847 | Yardley and Statham trademark registered. |

| 1853 | Gladstone removes the tax on soap. |

| 1883 | New factory built at Ridgmount Street, Bloomsbury. |

| 1890 | Thomas Gardner converts Yardley into a Joint Stock Company, Yardley & Co. Ltd. |

| 1900 | Yardley begins trading in Canada. |

| 1904 | New factory opened at Carpenters Road, Stratford, London. |

| 1905 | Yardley opens its first overseas wholesale outlet in Pitt Street, Sydney, Australia. |

| 1908 | New Products: Stick Shaving Soap. |

| 1910 | Display and retail sales shop opened at 8 New Bond Street, London. |

| 1913 | Yardley purchases an engraving of Francis Wheatley’s ‘The Flower-sellers’. |

| 1920 | Yardley converted into a Public Limited Liability Company. |

| 1921 | Yardley & Co. Ltd. New York established at 15 Thirty-Sixth Street, New York. Yardley receives its first Royal Warrant from the Prince of Wales. |

| 1923 | Yardley & Co. Ltd. Canada established in Toronto. New York office moves to Madison Square |

| 1924 | Yardley purchases the French perfumery Viville, which operates as Viville-Yardley. |

| 1927 | Yardley sales offices and showrooms moved to Pollen House, 10 Cork Street. W. A. Poucher engaged as consulting chemist and perfumer. |

| 1928 | Reco Capey joins Yardley to become its Art Director. Perfume laboratory and art studio established in Pollen House. |

| 1929 | William Poucher joins Yardley to become its perfumer-chemist. New Products: English Complexion Cream. |

| 1931 | Yardley’s London retail showrooms moved to Yardley House at 33 Old Bond Street, London. |

| 1932 | UK spirit duty on alcohol used in perfumes and toilet waters removed. Yardley & Co. Ltd. established in Union City, New Jersey. Yardley receives a Royal Warrant from Queen Mary. |

| 1933 | Yardley New York sales office and showrooms moved to the Rockefeller Center. London headquarters moved to Sackville House, Piccadilly. |

| 1934 | New Products: New formula Yardley Lipstick. |

| 1936 | New Products: Liquefying Cleansing Cream. |

| 1937 | Yardley opens a beauty salon in a building adjacent to Yardley House in Old Bond Street. New Products: English Complexion Powder; new formula Eyeshadow. |

| 1938 | New box making factory opens in the High Street, Stratford. |

| 1939 | Yardley subsidiary established in Australia. |

| 1940 | Yardley ordered to remove ‘English’ and ‘London’ from U.S. products by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission. |

Continue to: Yardley (post 1945)

First Posted: 5th March 2012

Last Update: 15th April 2024

Bouillette, P. L. (1955). William A. Poucher, the pioneer. The Journal of the Society of Cosmetic Chemists. VI(1). 69-74.

Jones, G. (2010). Beauty imagined: A history of the global beauty industry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Katharine Bertram (2015). Retrieved October 28, 2015, from http://www.katharinebertram.com

Lis-Balchin, M. (2002). Lavender: The genus Lavandula. London: Taylor & Francis.

Poucher, W. A. (1926). Eve’s beauty secrets. London: Chapman & Hall Ltd.

Poucher, W. A. (1932). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (4th ed., Vols. 1-2). London: Chapman and Hall Ltd.

Smith, R. (2008). A camera in the hills: The life and work of W.A. Poucher. London: Frances Lincoln Ltd.

Thomas. E. (1953). The house of Yardley 1770-1953. London: Sylvan Press.

Yardley & Co. Ltd. (1937). Beauty secrets from Bond Street [Booklet]. London: Author.

Charles Yardley junior [1824-1872]. His early death led to Thomas Exton Gardner [1839-1891] being put in charge of the firm. Thomas Gardner transformed the business in the nineteenth century and his two sons, Thornton E. Gardner [1873-1956] and Richard E. Gardner [1878-1939], would do the same in the twentieth century.

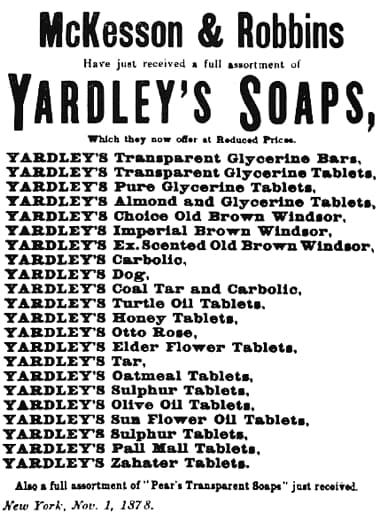

1879 Yardley soaps.

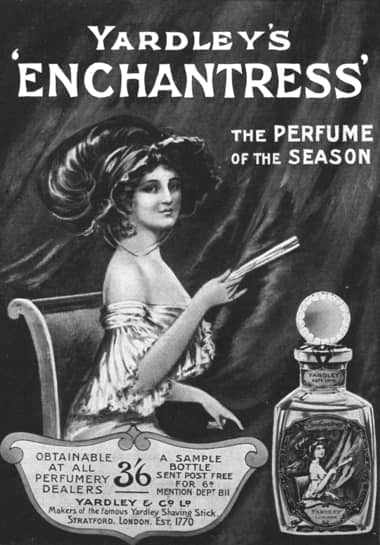

1912 Yardley Enchantress.

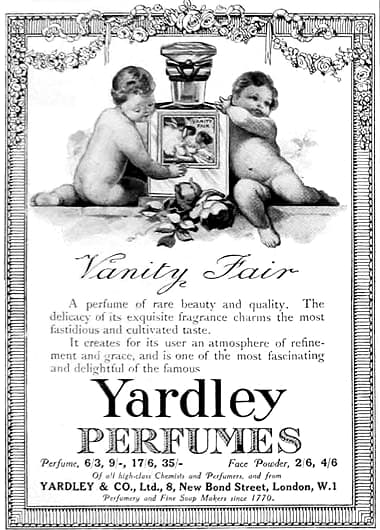

1918 Yardley Vanity Fair perfume.

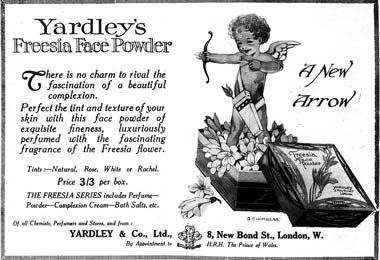

1923 Yardley Freesia Face Powder.

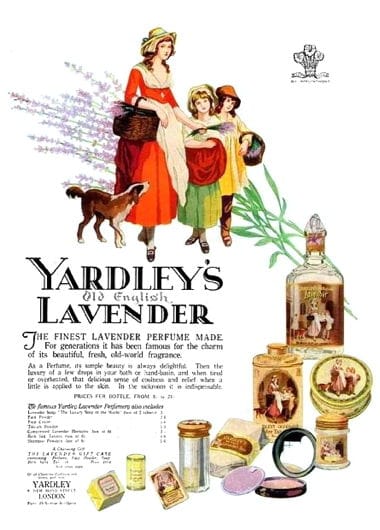

1926 Yardley Old English Lavender.

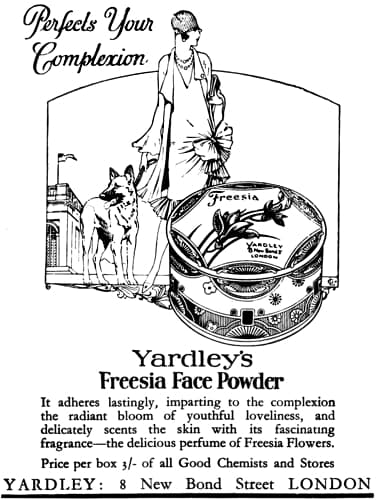

1927 Yardley Fressia Face Powder (Australia).

1928 Viville perfumes and cosmetics in containers designed by Yvonne Brunet.

1929 Yardley Lavender.

Yardley Complexion Cream. First introduced in 1929 it was sold in delicate ivory toned pots designed by the artist Reco Capey that are beautiful examples of Beatl™ moldings from the Beetle Products Co. Ltd.

W. A. Poucher [1891-1988] the author of Perfumes, Cosmetics & Soaps. This photo was taken in 1954, five years before he retired from the firm.

1946 Reco Capey [1895-1961] in his studio in Bond Street holding a Lotus perfume bottle he designed for Yardley.

Mrs. Olive Cato. She joined the company in 1935, was appointed cosmetic director of Yardley in 1937, and then made an executive director in 1963 to serve as chief advisor in matters connected with beauty products. This photo was taken around 1963.

1934 Olive Cato Products. Until she joined Yardley it would appear that Olive Cato ran her own cosmetics business.

1930 Yardley English Complexion Cream, English Lavender Face Powder and English Lavender Soap. The insignia at the top is for a Royal Warrant to the Prince of Wales, first issued in 1921. Presumably it lapsed when he abdicated. Later Royal Warrants issued to Yardley were: Queen Mary (1932), perfume; King George VI (1949), soap; Queen Elizabeth II (1955), soap; Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother (1960), perfume and other goods; and Charles, Prince of Wales (1995), toilet preparations.

1930 Yardley compacts.

1930 Viville-Yardley

1931 Door to the Yardley shop at 33 Old Bond Street.

1931 Yardley Shaving Bowl (wooden) and pot for Yardley Complexion Cream with seal.

1932 Yardley trade advertisement for English Complexion Powder.

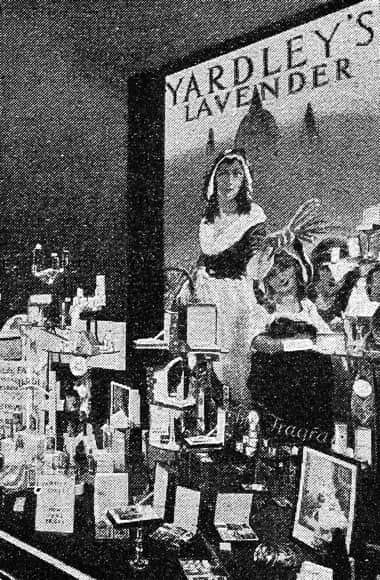

1932 Part of a shop window display of Yardley products.

1933 Yardley perfume, dusting powder and face powder perfumed with ‘Fragrance’.

1933 Yardley gifts for men and women.

1934 Entrance and lobby in the Yardley showrooms in the British Empire Building in the Rockefeller Center, New York.

1934 Lobby in the Yardley showrooms in the British Empire Building in the Rockefeller Center, New York.

1934 Yardley Lipstick.

1934 Yardley Lipstick encased in a steel-finished container with a brass band at the point where the cover comes off.

1934 Display case selector for Yardley Lipsticks.

1936 Yardley skin-care and make-up. The products shown are Skin Lotion, Toning Lotion, Skin Food, Rouge Cream, Foundation Cream, Lipstick, English Complexion Cream, Liquefying Cleansing Cream and Eyeshadow.

1936 Yardley gifts from Bond Street.

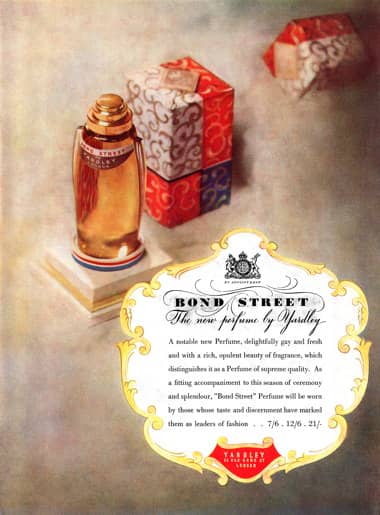

1937 Yardley Bond Street. One of Poucher’s most notable perfumes.

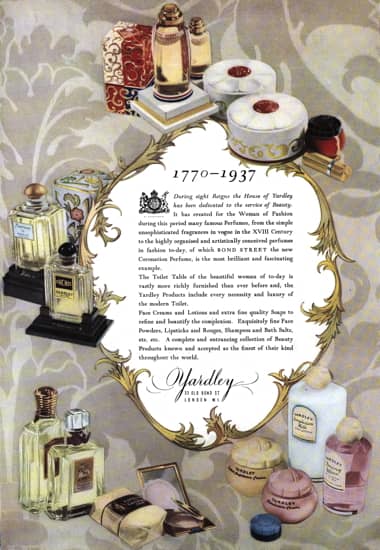

1937 Yardley celebrating the Coronation of King George VI.

1938 Katharine Bertram Capey née Stone [1908-1971] and Reco Capey.

1939 Yardley Shaving Bowl.

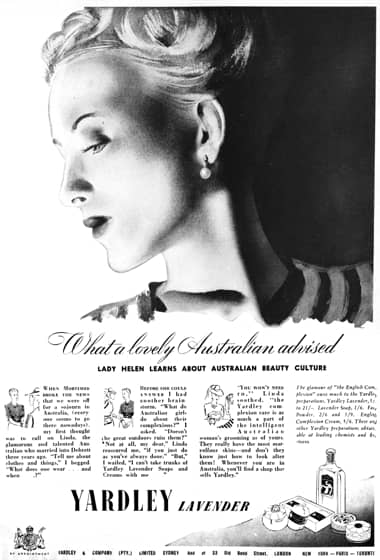

1939 Yardley Lavender (Australia).

1941 Yardley industry advertisement.

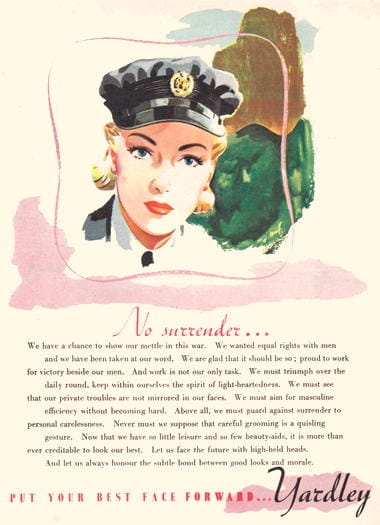

1942 Yardley No surrender ...

1942 Yardley of London (Australia).

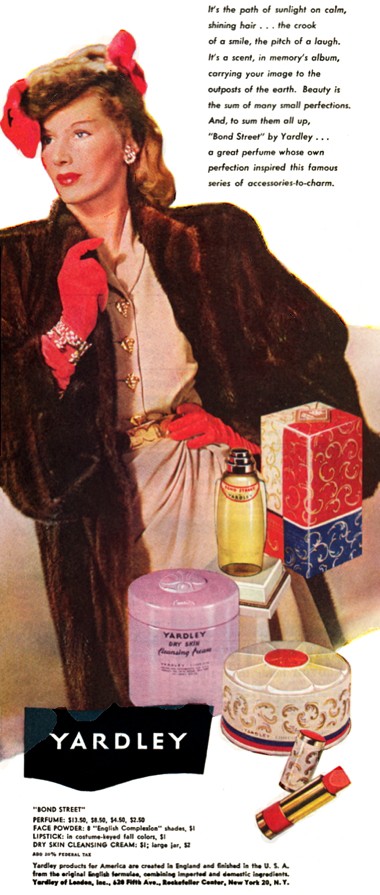

1942 Yardley Bond Street cosmetics. In 1940, Yardley was ordered by the FTC to remove from its U.S. products the words English and London or other references that might mislead consumers that Yardley products were made in England. The company responded by adding manufacturing information on the bottom of their advertisements.

1943 Yardley lipstick in cardboard wartime container.

1944 Yardley Bond Street Beauty Preparations including Dry Skin Cleansing Cream, English Complexion Powder (in 10 shades), Make-up Base, Lipstick (in 8 shades) and Bond Street Perfume.

1944 Some wartime Yardley products. Powder, English Lavender Fragrance and Foundation Cream are shown.