Interferential Treatments

In 1952, American newspapers began running reports of a new European beauty treatment using a machine that could ‘rejuvenate worn-out muscles’ with ‘scientifically-controlled electrical impulses’. The device featured in these reports was a Nemectron, named after its inventor Hans Nemec, a Viennese electrical engineer.

Nemectron

The Nemectron could stimulate nerves and muscles and produce muscle contractions, similar effects to those produced by faradic currents. However, the Nemectron used medium-frequency alternating currents rather than the low-frequency currents used in faradic treatments. Medium-frequency currents pass more easily through the skin than the low-frequency currents and reach deeper into the tissues with little or no discomfort to the client.

See also: Faradic Treatments

Unfortunately, electrical currents in the medium-frequency range are above 100Hz (hertz, cycles per second) and so are incapable of stimulating muscles or nerves. To get around this problem the Nemectron employed two medium-frequency currents not one. These were slightly out of phase and where they crossed the interference between them – hence the name interferential – produced a low-frequency current that was below the 100Hz needed to stimulate nerves and muscles. Nemec patented the process in a number of countries, including the United States (US:2,622,601, 1952).

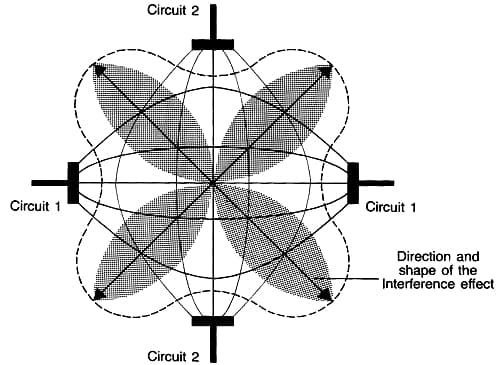

Above: Interference pattern of the interferential current generated by crossing two medium-frequency currents (De Domenico, 1981).

As two medium-frequency currents were needed, two pairs of electrodes were required, making four electrodes in total. One pair of electrodes carried a constant medium-frequency current, the other a medium-frequency current that could be varied. If, for example, the constant circuit was fixed at 4000Hz and the variable circuit at 4050Hz, a low-frequency interferential current of 50Hz was created where the two currents interfered with each other.

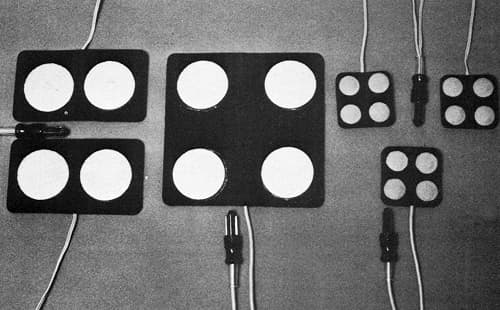

The electrodes used with the original Nemectron were pads held in place by a therapist or fixed to the body.

Above: Assorted interferential pads.

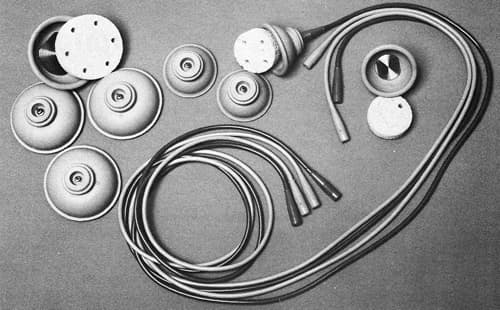

Some later machines made by Nemectron, or others after the patent ran out, employed suction cups to hold the electrodes in place during body treatments and/or small hand-held quadripolar electrodes in facial treatments.

Above: Suction cups, one for each electrode.

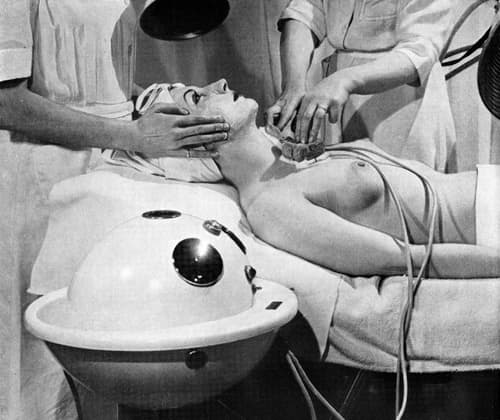

Above: Hand-held quadripolar electrode.

Treatments

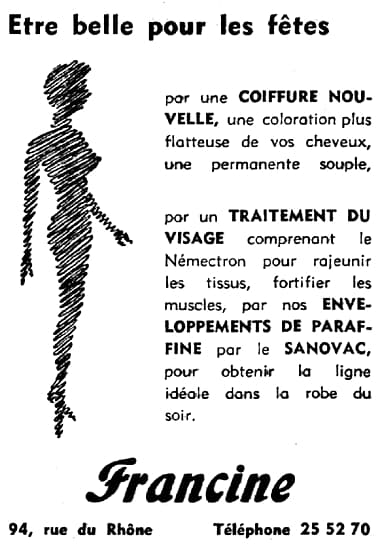

Interferential machines were adopted by Beauty Culture well before they became popular with physiotherapists. French salons that used Nemectrons in the 1950s included Helena Rubinstein, N. G. Payot and Orlane. By the middle of the decade they were also found in salons outside Europe in places like Brazil and Australia, then somewhat later in the United States. Their popularity with salons might explain why the Nemectron company began manufacturing other salon machinery such as vaporisers and brush machines.

Above: c.1955 The attendant on the left is using an infra-red lamp to increase the penetration of a face cream while that on the right is using a Nemectron to firm the décolletage (Mayer, 1955).

Very wide beauty claims were made by Nemectron for its interferential treatments. The extent of these claims can best be seen in the 1960 U.S. Food and Drug Authority (FDA) notice of judgment made against the Nemectron company for false and misleading representations.

CHARGE: 502(a)—when shipped and while held for sale, the labeling which accompanied the article contained false and misleading representations that the article was effective for toning the body; strengthening the body; regenerating the tissues; rejuvenating the body; producing beneficial effects on the cells and tissues of the body, including the nerves, muscles, glands, and brains; overcoming the damages and ravages of age; restoring the lost elasticity of the skin; removing deposits of fat (double chin), and obnoxious toxic substances caused by impaired cellular metabolism; removing wrinkles and furrows; improving cellular metabolism; accelerating venous and lymphatic circulation, thus overcoming cellulitis and acne; “normalizing” a condition of underdevelopment of the breasts and overdevelopment of the breasts; overcoming a condition of atonic abdominal muscles; strengthening the feet; eliminating edema and infiltration of the ankle and calf; and overcoming a condition of fallen arches.

(FDA Notice of Judgement, October, 1960)

In salons, the claims for interferential treatments were similar to those for faradic treatments – muscle contraction, improved blood and lymphatic flow, and increased tissue metabolism. Like faradic treatments they were used in body sculpting and cellulite treatments, including bust improvement and ankle reductions, as well as to strengthen facial muscles in anti-wrinkle and facial contour treatments. Although their popularity for use in beauty treatments waned somewhat in the 1960s they can still be found in some salons today.

2nd March 2020

Sources

Cressy, S. (2004). Beauty therapy fact file (4th ed.). Oxford: Heinemann Educational Publishers.

De Domenico, G. (1981). Basic guidelines for interferential therapy. Sydney: Theramed Books.

De Domenico, G. (1987). New dimensions in interferential therapy: A theoretical & clinical guide. Lindfield, NSW: Reid Medical Books.

Goats, G. C. (1990). Interferential current therapy. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 24(2), 87-92.

Mayer, C. (1955). La médecine au service de la beauté. Paris: Amiot-Dumont.

Simmons, J. V. (1989). Science and the beauty business. Volume 2. The beauty salon and its equipment. London: Macmillan.

Ward, A. F. (1986). Electricity fields and waves in therapy. Marrickville, NSW: Science Press.

Dr. Hans Nemec [1907-1981].

1954 Nemectron demonstration in Brasil.

1955 Nemectron treatments at the Instituto Cientifico de Estética Cosmética, Brasil.

1956 Orlane Nemectron ankle treatment (France).

1956 ‘Nemecure’ treatment in the Rene Henri salon, Sydney, Australia.

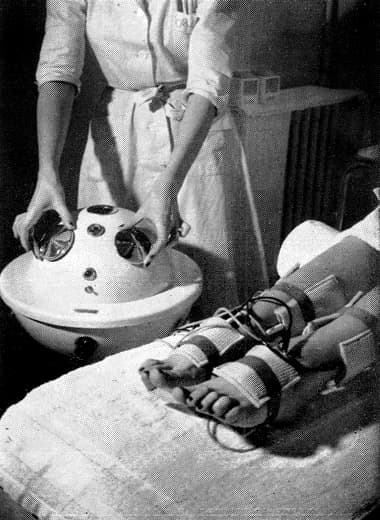

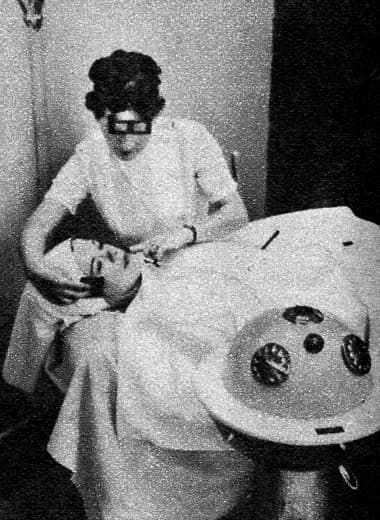

1959 Facial treatment using a Nemectron, Geneva.

1964 Publicity shop for the FDA examination of the Nemectron. The circular electrode Irving Pollack has placed on the arm of Margaret Joseph was meant for breast treatments.