Patent Medicines and Cosmetics

The production and sale of patent medicines became a major industry in the second half of the nineteenth century. This was particularly so in the English speaking world with excesses in the trade being very noticeable in the United States. The peak of the patent medicine trade was associated with the rise of cosmetics as a modern industry, which was more than just coincidence. Modern cosmetics, like many other commodities, owes a debt of gratitude to patent medicines.

Proprietary medicines

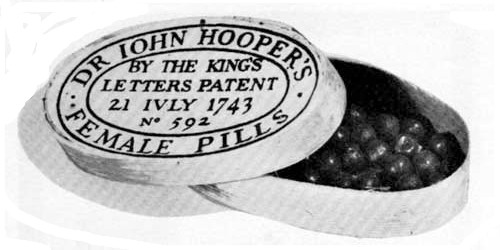

Although widely used, the expression ‘patent medicine’ is misleading. The term originated in the seventeenth century through the use of royal monopoly grants – ‘letters patent’ or ‘litterae patentes’ – for products and services including the manufacture of medicinal compounds.

Above: 1743 Doctor John Hopper’s Female Pills granted letters patent.

Although nineteenth century patent medicines were often trademarked, most were not covered by either ‘letters patent’ or a pharmaceutical patent – a twentieth century development – so legally they are more correctly described as ‘proprietary medicines’ sold ‘over-the-counter’. Significantly, patent medicines did not usually disclose their chemical composition, a requirement for drugs patented in the modern sense of the word.

Patent medicines

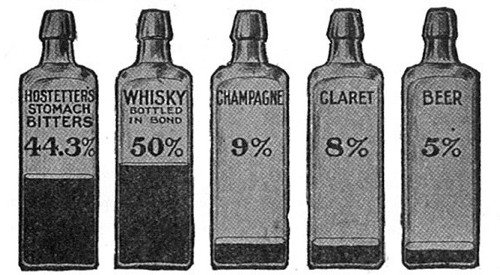

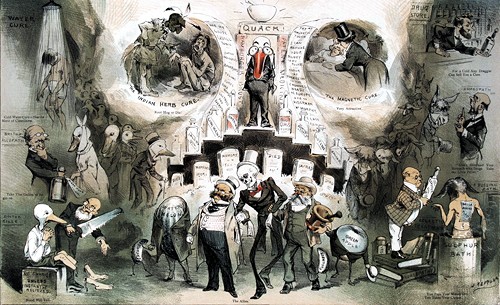

Often fortified with large amounts of alcohol, morphine, opium or cocaine, patent medicines claimed to cure a wide variety of ailments ranging from indigestion to ‘female complaints’ and cancer.

Above: The alcohol content of Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters compared with whisky, champagne, claret and beer (Adams, 1905, p. 16). Many religious organisations that actively supported the temperance movement were shocked to find that patent medicines advertised in their publications contained high levels of alcohol.

Gullible America will spend this year some seventy-five millions of dollars in the purchase of patent medicines. In consideration of this sum it will swallow huge quantities of alcohol, an appalling amount of opiates and narcotics, a wide assortment of varied drugs ranging from powerful and dangerous heart depressants to insidious liver stimulants; and, far in excess of all other ingredients, undiluted fraud. For fraud, exploited by the skillfulest of advertising bunco men is the basis of the trade.

(Adams, 1905, p. 3)

Although enterprising individuals with no medical or pharmaceutical credentials were often responsible for the more ‘colourful’ products on the market, qualified pharmacists and large pharmaceutical firms were also involved in the trade, so not all products regarded as patent medicines were worthless.

The reasons for the boom in patent medicines sales in the late nineteenth century were varied. General mistrust of doctors and the high cost of medical services remained a factor, as did the poor living standards and the general poverty that characterised many of the inhabitants of the rapidly expanding nineteenth century cities.

Above: 1881 Death’s-Head Doctors – Many Paths to the Grave by Joseph Keppler which illustrates the general distrust of the medical profession of the time.

However, expansion of the patent medicine trade in the second half of the nineteenth century was also fuelled by three industrial developments that gained pace then: the expansion of rail and steamship transportation that made the distribution of goods more efficient; the introduction of affordable postal services which lowered the costs of mail-order businesses; and the growth of the popular press which allowed manufacturers to advertise nationwide.

Patent medicine advertising

The nineteenth century patent medicine market was very crowded and to be lucrative products needed to reach a national audience. This required patent medicine firms to outlay large sums of money on promotion – a fact of life later shared by cosmetic companies – often committing half or more of their income on advertising. Given the size of these advertising budgets it is not surprising that patent medicines were the lifeblood of many nineteenth century publications.

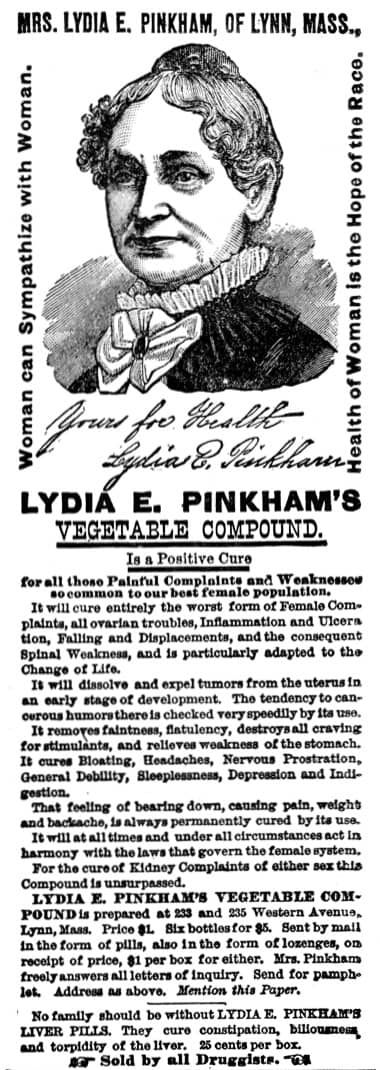

As most advertising copywriting for patent medicines was done by someone connected with the business, determining what sort of advertising generated the best sales was largely a matter of trial and error – only later in the century was this task passed to the developing advertising agencies. However, those patent medicines sold through mail-order could quickly determine the effectiveness of their advertising through the number of orders that followed. Those that generated large orders within a few days of their placement were duly noted and repeated, those that did not were modified or abandoned. For example, the decision by the Pinkham family to prominently position their mother’s image in an advertisement for Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound led to a boom in sales and the continuous use of this image as a trademark even after Lydia Pinkham’s death in 1883.

Given the length of time patent medicines had been on sale, and the money to be made from successful promotions, the patent medicine industry became a major force in the development of effective mass advertising and in the establishment of the modern advertising industry.

But if patent medicines, lotteries and fakery in general gave disrepute to early advertising they also helped establish advertising, for it was their big successes that revealed the potentialities of selling through print. They nursed mediums. They developed copy and mechanics. They tested and determined the value of positioning in the newspapers. At every stage in the early growth of advertising it was the patent-medicine trade that was giving the subject the most thought and developing new devices. In England the earliest outdoor advertisers were the patent-medicine and lottery men, and in nearly every other medium they either originated the new method or were the first to use it in a large way. When advances in distribution and serious consideration of advertising made the business world ready it found prepared and waiting a force that had been functioning and proving itself for several hundred years and had its power well demonstrated.

(Presbrey, 1929, pp. 299-300)

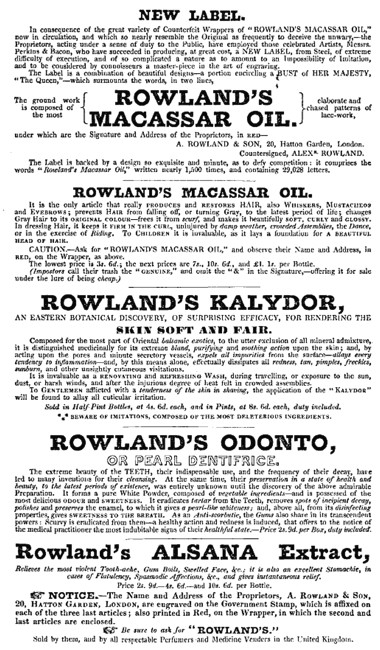

The cosmetic industry, perhaps more than any other, capitalised on the advertising expertise originally developed to sell patent medicines. Cosmetic advertising of the period frequently appeared alongside placements for patent medicines and copied a number of its advertising techniques. In no particular order these included:

- wide claims of efficacy;

- suggestions that a product had mysterious, secret or exotic origins;

- inclusion of female images in advertising aimed at women;

- claims that the product was a scientific breakthrough backed by members of the scientific or medical professions;

- assertions that the product was safe and had been extensively tested, combined with a list of harmful materials that were absent;

- testimonials from satisfied customers;

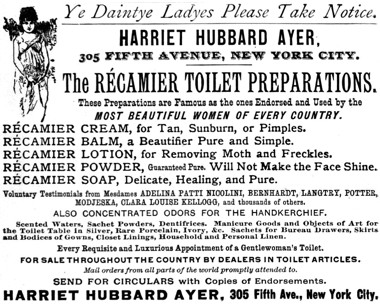

- endorsements from celebrities, particularly from the theatrical profession;

- use and defence of easily recognised trademarks;

- repetition of keywords and catchphrases;

- offers of free booklets to be sent by post;

- invitations to readers to write in for personal advice;

- insertion of product leaflets into materials sent by mail-order;

- guarantees of money back if not satisfied; and

- offers of trial samples.

As with patent medicines, advertising was a key factor in driving cosmetic sales. The debt owed by the growing cosmetics industry to the well-established patent medicine trade was therefore substantial. As well as building a comprehensive advertising toolkit that the cosmetics industry went on to use, the patent medicine trade helped stimulate the development of the modern advertising agency which the cosmetics industry would come to rely on in the twentieth century. Unfortunately, there was a negative side to this relationship as well.

Regulation

As the patent medicine trade boomed it came in for increasing criticism from the medical profession. In Britain, the British Medical Association’s journal ‘The Lancet’ exposed some of the excesses in the trade and this led to the passing of a number of Acts of Parliament including the ‘Pharmacy and Poisons Act’ (1868) and the ‘Sale of Food and Drugs Act’ (1875). Similar campaigns were run in the United States but organised resistance there was stronger – from trade organisations, members of Congress with vested interests, and proprietors of publications that received substantial revenues from patent medicine advertising – so it would not be until 1906 that Federal Government passed the Pure Food and Drug Act. This act led to the creation of a body to regulate food safety which was renamed the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1930.

The line between cosmetics and patent medicines was unclear. Many companies included patent medicines and cosmetics in their product range and/or made medical or quasi-medical claims for their cosmetics and toiletries. It is not surprising then that attacks by the medical profession on patent medicines would spill over into cosmetics. Like patent medicines, many doctors regarded cosmetics as a waste of money, rife with bunkum, and the source of health risks.

The assault on cosmetics was particularly virulent in the United States where Dr. Morris Fishbein [1889-1976] – editor of the ‘Journal of the American Medical Association’ (AMA) and its lay publication ‘Hygeia’ – invested a large amount of time and energy into attacking the cosmetic industry there. The first major confrontation between the AMA and the American cosmetic industry occurred in the 1920s over complexion clays but other issues followed including the use of hormones in skin creams, paraphenylenediamine in hair dyes, and thioglycolic acid in permanent waving.

See also: Complexion Clays and the A.M.A., Hormone Creams, Oils and Serums and Lash Lure

The AMA also gave its support to the passing of the 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act which extended many of the provisions of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act to cosmetics and placed major restrictions on cosmetics advertising in the United States.

Updated: 7th August 2015

Sources

Adams, S. H. (1905). The great American fraud. New York: F. P. Collier & Son.

Armstrong, D. & Armstrong, E. M. (1991). The great American medicine show. New York: Prentice Hall.

Bok, E. W. (1920). Cleaning up the patent-medicine and other evils. Printers’ Ink. 113 129-130, 133.

British Medical Association. (1909). Secret remedies. London: Author.

British Medical Association. (1912). More secret remedies. London: Author.

Griffenhagen, G. B., and Young J. H. (1959). Old English patent medicines in America. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute. Available from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/30162/30162-h/30162-h.htm

Peiss, K. (1998). Hope in a jar: The making of America’s beauty culture. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Powell, G. H. (1908). Powell’s practical advertiser: A practical work for advertising writers and business men, with instruction on planning, preparing, placing and managing modern publicity. New York: Author.

Presbrey, F. (1929). The history and development of advertising. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc.

1842 A range of products from Rowland & Sons, London. Some items such as Rowland’s Macassar Oil were cosmetics but made patent medicine-like claims of ‘producing and restoring hair’. Others, such as Rowland’s Alsana Extract, used to relieve tooth-ache, gum boils and indigestion, were clearly patent medicines.

1882 Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound for ‘female complaints’. It contained large amounts of alcohol.

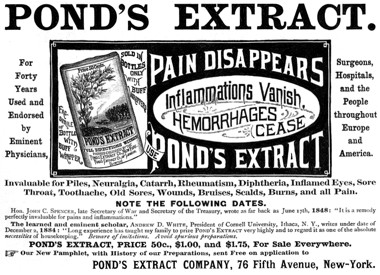

1886 Pond’s Extract Company. Pond’s started out in 1846 selling Pond’s Extract as a patent medicine before moving into cosmetics with the introduction of Pond’s Extract Cold Cream and Pond’s Extract Vanishing Cream in 1904.

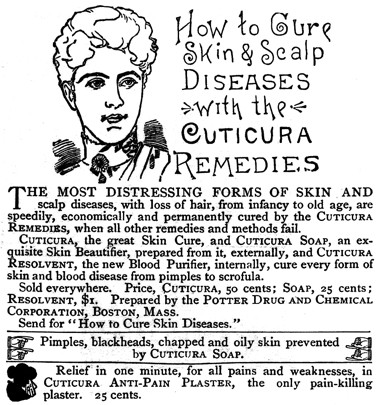

1890 Cuticura. Manufactured by the Potter Drug and Chemical Company. The Cuticura range included toiletries, cosmetics and patent medicines.

1891 Récamier Toilet Preparations from Harriet Hubbard Ayer endorsed by theatrical celebrities such as Sarah Bernhardt and Lillie Langtry. Harriet Hubbard Ayer also sold Vita Nuova, a patent medicine which was claimed to treat dyspepsia, nervousness and malaria.

1896 Assorted cosmetic and patent medicine advertisements from the Ladies’ Home Companion.

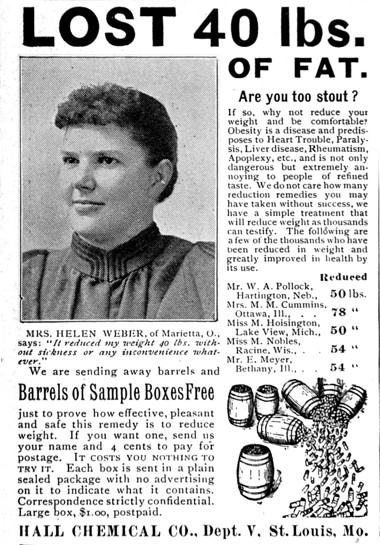

1899 Diet pills from the Hall Chemical Company of Missouri. Weight loss pills were a major class of patent medicines.

1909 Rex Complexion Powder advertisement using many of the advertising strategies developed to sell patent medicines.