Complexion Clays and the A.M.A.

By the second decade of the twentieth century there was a lot of optimism in America about its developing beauty industry.

Nowadays, with all the wonderful new beauty specialists and inventions, the creams adapted to every purpose and suited to every type of skin, the powders matched to every complexion to a nicety, the rouges, the lipsticks, the eyebrow pencils, the wrinkle eradicators, massage, mud packs, muscle oils, permanent waving, etc.—why should any woman be plain?

(Mason, 1917)

America’s entry into the First World War in April, 1917 and the post-war depression of 1920-21 put a temporary damper on things but as the ‘Roaring Twenties’ got underway there was a dramatic rise in the acceptance and use of cosmetics. The 1920s also saw the arrival of America’s first modern beauty craze – complexion clays.

Clay treatments

Until the 1920s, complexion clays had been largely restricted to commercial outlets like spas, beauty parlors and barber shops. The change to a general consumer product happened very quickly with a number of companies introducing complexion clays into the American market by 1922. Each company promoted their particular clay, aiming their advertisements both at individuals and at the myriad of small beauty shops that opened during the decade.

Companies

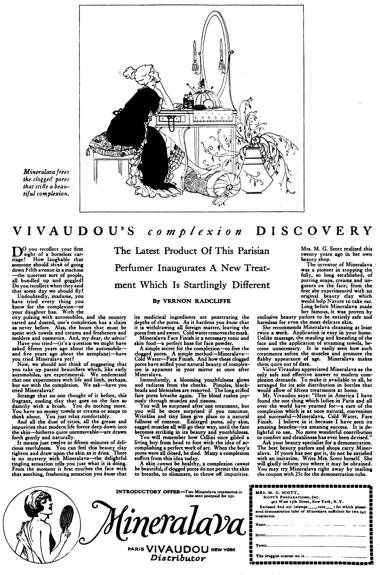

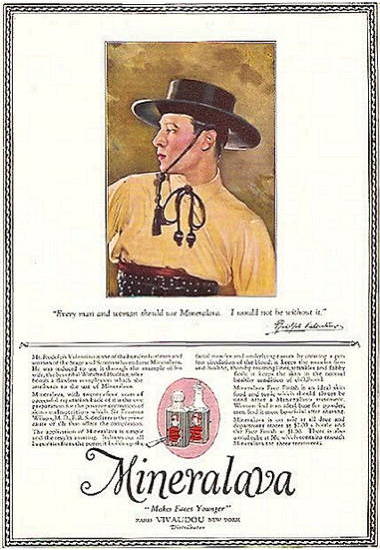

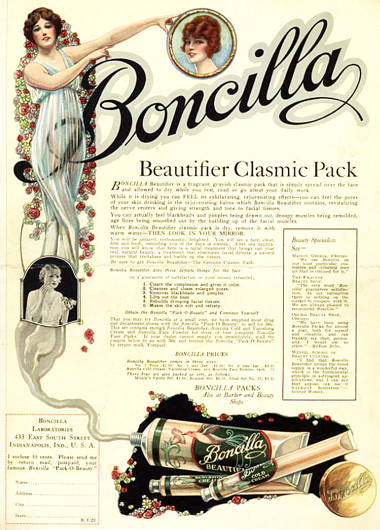

Two of the main participants in the beauty clay fad were Boncilla Laboratories Boncilla Beautifier and Scott’s Mineralava. Mrs. M. G. Scott claimed to have been using Mineralva in her own beauty parlor since 1889 – but late in 1921 it began to be distributed through V. Vivaudou, Inc., and it is around this time that it was repackaged and marketed for personal use. The Bonciller Beautifier arrived in 1916 as a product from the Crystal Chemical Company which changed its name to Boncilla Laboratories in 1920.

Above: 1923 Boncilla and Mineralava beauty clays from a Jones Bros. & Company, Ltd. catalogue.

Victor Vivaudou, famous perfumer, discovered that better Beauty Shops were using a preparation so wonderful in its effect upon the complexion, that he arranged for its sole distribution in the home. “I have seen its amazing benefits—its amazing success. It is delightful to use. No more wonderful contribution to comfort and cleanliness has ever been devised!”

(Mineralava advertisement, 1921)

See also: V. Vivaudou and Boncilla

Mineralava generated a lot of newsprint in 1923-24 when it engaged Rudolph Valentino and his wife to be, Natacha Rambova (née Winifred Hudnut), at US$7000 a week to tour the United States. The couple promoted the virtues of Mineralava while performing dances exhibitions and judging beauty contests. Valentino needed the money as he had gone on strike in 1922 from the ‘Famous Players-Lasky’ studio over creative control and pay issues. His tour marked the high point of the complexion clay fad in the United States.

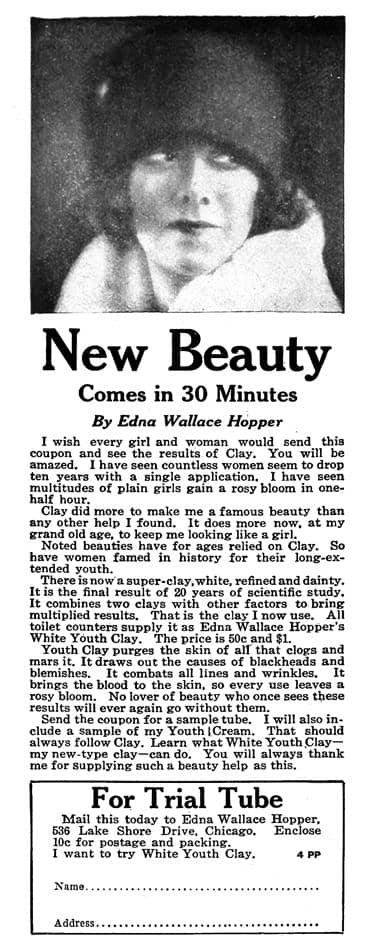

Other companies that sold beauty clays in the American market included Century Chemists (English Complexion Clay, also known as Ryerson’s Forty Minute Beauty Clay), Dermatological Laboratories (Terra-Derma-Lax), Domino House (Complexion Clay), Edna Wallace Hopper (White Youth Clay), and Marguerite Sullivan (Complexion Clay).

Above: 1922 Some complexion clays available in the United States: Mineralava Beauty Clay, Boncilla Clasmic Beautifier, Ryerson’s Forty Minute Beauty Clay, Terra-Derma-Lax, and Domino Complexion Clay.

One variation on the complexion clays of the 1920s were those made from radioactive sources, a good example being Kemolite, owned and promoted by Phyllis Earle in Britain. These did better business in Europe and the United Kingdom than they did in the United States.

See also: Radioactive Cosmetics

Claims

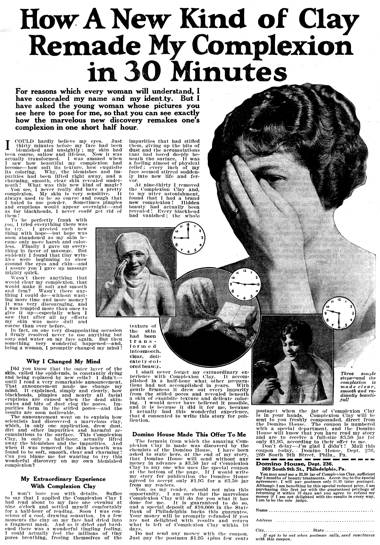

Claims made for complexion clays generally concentrated on their ability to ‘unclog pores’ and ‘draw out skin impurities and poisons’.

Complexion Clay does not cover up blemishes and impurities—but removes them at once. It cannot harm the most sensitive skin. There is a feeling almost of physical relief as the facial pores are relieved, as the magic clay draws out the accumulated self-poisons and impurities. You will be amazed when you see the results of only one treatment—the whole face will appear rejuvenated. Not only will the beauty of your complexion be brought to the surface but enlarge pores will be normally closed, tired lines and bagginess will vanish, mature lines will be softened. Complexion Clay brings life and fervor to every skin cell and leaves the complexion clear, firm, smooth, fresh looking.

(Marguerite Sullivan advertisement, 1922)

Convincing consumers that this was true was made easier by the fact that the clays generated a noticeable tightening sensation as they dried.

As it dries it contracts. You feel its medicinal ingredients penetrate the depths of the pores. You feel it withdraw foreign matter. You feel the wrinkles smooth out. You feel the flabby skin made tight. You feel the cleansing purifying blood tingle through each tiny vein.

(Mineralava advertisement, 1921)

Application

Using a complexion clay was not difficult. After cleansing the face the mud was applied using the fingers or a brush and left in place for 30-40 minutes, after which it was removed with wet towels. The most important thing to remember was not to move any facial muscles during the treatment, otherwise the clay would crack and the tightening effect would be lost.

Mud Packs or Masks have recently been introduced as a means of temporarily refreshing the skin. … The face is first cleaned with a little cream, all traces being subsequently removed, and then the mud is applied fairly thickly, all over the face and neck. A small margin is left round the eyes. The effect on the skin is at first cooling, and as the paste dries this sensation is followed by “tightening,” it being quite impossible to keep the lips together. The face is fanned to hasten the formation of a mask, and it is imperative that no movement of the face muscles occur, otherwise the mask splits and the results are not good. … It is removed by the application of wet towels.

(Poucher, 1926, pp. 33-34)

The American Medical Association

In 1923, the Chemical Laboratory of the American Medical Association (AMA) published a review of complexion clays then on the American market. Their analysis – based on a report in the publication ‘Hygenia’ – indicated that all the products were essentially made from clay and water.

Unfortunately, the report makes no mention of the type of clays that were used. These came from a range of sources, some indigenous to the United States, others were imported from overseas, and probably included montmorillonite, bentonite, Fullers’s earth, and kaolin. Given its name, Mineralava may have been made of montmorillonite as this type of clay is generally derived from volcanic rocks.

The AMA objected to the exaggerated claims manufacturers made for complexion clays and to their exorbitant cost, a charge they had previously levelled at patent medicines. Quoting Dr. Cramp from ‘Hygenia’ – the original source for much of the article – they noted that:

Great is the power of words and wonderful the potentialities of modern advertising. Who would have believed that so prosaic a product as clay could be endowed with such esoteric qualities? A study of the ‘patent medicine’ business convinces one that with the right kind of advertising ‘copy’ and a large advertising appropriation one could become rich by selling pink dish-water as a curative agent.

(A.M.A., 1923, p. 80)

The American cosmetic industry responded to the AMA’s complaints by commenting that, although some claims may have been “clothed in the fanciful vernacular of an over-zealous sensationalist” (AP&EOR, 1923), the AMA’s tests indicated that there were no harmful ingredients in the clay and that their main allegation was that the prices charged were very high. This they regarded was as a matter of supply and demand; besides, as they saw it, the medical profession itself was not immune to criticisms for over-charging.

Physicians and surgeons, who are more hasty than pharmacists in criticisms of charges for service made by other people, are not at all immune from going on the defensive. The court and other records are filled with reports of obviously exorbitant fees, often assessed when the patients died.

(AP&EOR, 1923)

The AMA and ‘Hygenia’ reviews were widely reported in the press in 1923. The criticisms were serious but were probably not nearly as damaging as the fact that the review included a formula for making a complexion clay.

Here is a helpful hint for those women who think the path to beauty lies through the clay route: Go to your neighborhood druggist and purchase a pound of kaolin (dried, powdered clay). It will cost about twenty cents. Mix it with the same amount of water. You will then have two pounds of beauty clay equal in beautifying power to, and purer than, any of the products on the market that are sold for from $2.00 to $10.00 a pound. The only thing you will lack is the mental uplift produced by reading the ineffable bosh published by the complexion clay exploiters.

(A.M.A., 1923, pp. 80-81)

The effect on manufacturers’ sales and profits of individuals mixing up their own complexion clays, rather then buying them ready made, was noted in the trade press.

New beauty shoppes and parlors are springing up all over the country every day (observe it is not weekly but daily), and in all of them the mud-pack for the face is a feature, but there is a deadly fly in the manufacturer’s pot of profits. The operators of all these new enterprises are rolling their own ingredients into their own pet, personally endorsed preparation, made with a little kaolin, one of the cheapest items a drug store offers, some water, a dash of perfume, a little glycerine, following the A.M.A. formula. Naturally the $2 to $10 a small jar manufacturers are in the doldrums, one large company becoming peevish, but there is no reason why they should despair. The “Money in Mud” has not all been extracted. Revision of their prices and methods, by eliminating fabulous profits, might easily convert their present status into a safe, secure and permanent industry.

(AP&EOR, 1924)

The fabulous profit margins of complexion clays evapourated after 1924 and many firms then lost interest in them. However, complexion clays in one form or another continued to be sold, and clay packs – especially those that were salon made – have remained a staple beauty treatment to this day.

See also: Clay Masks

As well as being America’s first modern beauty fad, complexion clays generated the first review by the AMA of a class of cosmetics. Up until then it had concentrated mainly on quackeries and patent medicines with only the occasional mention of specific beauty products.

See also: Patent Medicines and Cosmetics

The AMA was to become increasingly vocal about cosmetics in the future and the following year it published a report on hair dyes. This would lead to a number of confrontations in succeeding years with the beauty industry and play a part in the eventual passing of the Wheeler-Lea Act and the American Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act (FD&CA) in 1938 despite attempts by the cosmetic industry to fend it off.

See also: The FDA, FTC and Cosmetics

In 1949, the AMA also established a Joint Committee on Cosmetics to “study problems relating to medical interest in cosmetics and to effect a better understanding of the usefulness of cosmetics” (JAMA, 1949). The committee members included doctors, dermatologists, pharmacologists and a single consumer advocate (Good Housekeeping Magazine), but no representative from the cosmetic industry.

First Posted: 3rd June 2013

Last Update: 25th March 2025

Sources

The American perfumer & essential oil review. (1923). November. New York: Perfumer Publishing Company.

The American perfumer & essential oil review. (1924). April. New York: Perfumer Publishing Company.

Chilson, F. (1934). Modern cosmetics. New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

Committee on cosmetics (1949). Journal of the American Medical Association. 140(4), 406-407.

Maison, M. (1917). New year vs. cosmetics, a plea for the defense. New York: The United Press.

Money in mud. (1923). In Annual Reports of the Chemical Laboratory of the American Medical Association. Vol. 16. Chicago: American Medical Association.

Poucher, W. A. (1926). Eve’s beauty secrets. London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.

Robertson, R. H. S. (1986). Fuller’s earth: A history of calcium montmorillonite. Hythe, Kent: Volturna Press.

Smith, A., & Rockwood, R. (1935). Modern beauty culture. New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

1920 Scott’s Mineralava.

1921 Scott’s Mineralava distributed by V. Vivaudou.

1922 Terra-derma-lax.

1922 Ryerson’s Forty Minute Beauty Clay.

1922 Domino Complexion Clay.

1923 Youth Glo Facial Clay.

1923 Mineralava advertisement promoting the Valentino tour. Note the updated packaging.

1924 Phyllis Haver [1899-1960] as Gertrude Trayle having a Mineralava treatment in the film ‘The Perfect Flapper’ (First National Pictures).

1925 Edna Wallace Hopper White Youth Clay.

1927 Boncilla Beautifier Clasmic Pack.