Waxing

There are a number of ways that superfluous hair can be removed from the body, some more recent others used for millenia. Removing hair by enmeshing it in a semi-solid, wax-like material and then ripping it out by the roots with a sharp ‘yank’ is a very old practices, made possible because the force required to pull hair out by its roots is normally less than that required to break the hair itself.

See also: Hair Removers

In the beauty industry, this epilating method is generally known as ‘waxing’ with terms like ‘hot wax’, ‘strip wax’, ‘cold wax’ and ‘cool wax’ commonly employed, despite the fact that many of the mixtures used to remove hair this way do not contain any wax whatsoever.

A good example of this comes from the nineteenth century where the well-known but infamous Marie Gilbert, a.k.a. Lola Montez [1821-1861], recommended removing unwanted hair using a mixture made from gum resin and pitch spread on leather, a method that goes back to Roman times.

Spread on a piece of leather equal parts of galbanum and pitch plaster, and lay it on the culprit hairs as smoothly as possible, and then, after letting it remain about three minutes, pull it off suddenly, and it will be quite sure to bring out the hairs by the roots, and they will not grow again. The pain of this operation is much less than the cauterizing remedy, and is, besides, more successful. I have seen poor victims sit all day pulling these aggressive hairs with tweezers, which is a fruitless task, for they almost invariably break off the hair at the neck, instead of pulling it out by the roots.

(Montez, 1858, pp. 91-92)

Medical epilation

A number of nineteenth and early twentieth-century medical treatments also involved pulling the patient’s hair out by its roots. For example, hair removal was once considered an important part of any treatment for fungal skin infections such as ringworm or favus, both common complaints of young children.

In the treatment of favus patience and method are of more value than any special medication. Without perseverance on the part of both physician and patient it will be impossible to cure a case. Epilation, cleanliness and parasitides are the means at our command for combating the disease.

(Jackson, 1898, p.270)

In the case of favus of the head, removing the hair could be done with forceps but a pitch-cap or ‘callotte’ was also used. This was developed in the 1820s by the Mahon brothers at the Hôpital Sant-Louis, Paris as a treatment for ringworm. Like the epilation method recommended by Lola Montez, the ‘callotte’ used pitch spread on leather to enmesh the hair which was then ripped off; a risky procedure. Parts of the scalp could be also torn off with the epilated hairs leading to infection, scarring and sometimes even death.

The “calotte,” or pitch-cap, is the most rapid means of epilating, but it is painful and sometimes dangerous. The “calotte” is composed of,

Vinegar 150 parts Wheat flour 25 parts Black pitch 25 parts White pitch 25 parts made into a mass and spread on leather. This is applied, while soft, to the whole head, and when it has set, it is pulled off suddenly by taking hold of the part over the forehead, and removing it from before backwards.

(Jackson, 1898, pp. 271-272)

Epilating sticks

Given the risks associated with the ‘callotte’, many doctors preferred to pull the hair out with forceps or used an epilating stick. These were similar to the small sticks of wax used to seal letters before adhesive envelopes came into common use. An early example formulated by the German dermatologist Paul Gerson Unna [1850-1929] was made from a mixture of 9 parts resin and 1 part beeswax.

When employed, one end of the stick was heated – but not so much that it burned the skin – and the warm end was then pushed into the skin with a boring movement on the part to be epilated. When it cooled, the stick was then removed with a sudden twist pulling the embedded hair out with it. The hair stuck on the end of the stick was then burnt off before the procedure was repeated.

Using an epilating stick was laborious for the practitioner and painful for the patient and by the beginning of the twentieth century the medical profession had largely discarded this form of epilation and many doctors had unfortunately shifted to removing hair with X-rays which had long-term, adverse consequences for many of their patients.

See also: X-rays and Hair Removal

Although epilating sticks were largely abandoned by the medical profession by the early part of the twentieth century they continued to be used in the beauty industry and number of patents were taken out for them. Two formulas are included below:

Oil of skunk 1 part Oil of eucalyptus 1 part Oil of bergamot 1 part Gum camphor 3 parts Burgundy pitch 4 parts Beeswax 20 parts Rosin 69 parts These ingredients are to be thoroughly mingled by heating and stirring, and when so mingled then to be molded in bars of suitable size and shape.

(US patent No. 949,925, 1910)

Resin 5 per cent. Carnauba wax 20 per cent. Boiled linseed oil 10 per cent. White wax or

hard paraffin wax5 per cent. [T]he resin, carnauba wax and white wax or paraffin wax, are heated and dissolved together, and when cooling from their liquid state, the boiled vegetable oil is added, and thoroughly mixed with the same; and the material is then taken and formed into cylinders or “sticks” in suitable moulds in which it solidifies.

(British patent No. 209,997, 1924)

Women did not necessarily use these sticks in the same manners as doctors. In a 1901 newspaper article entitled ‘Means employed to destroy beards on women’s faces’, Harriet Hubbard Ayer [1849-1903] describes heating a stick ‘depilatory’ before smearing it across the skin to form a plaster. This was then removed in much the same way as modern epilatory waxes by gripping a teased edge and then quickly pulling the wax off the skin and the hair with it.

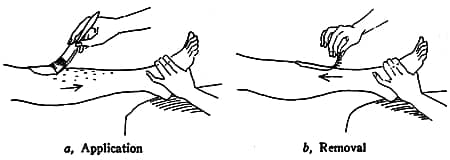

Above: Using a plaster stick to remove facial hair (Ayer, 1901)

The plaster stick depilatory is a mixture of pitch and resin, highly adhesive. The stick is heated over a small spirit lamp, and while hot enough to run, but not hot enough to burn the skin, is applied to the hairy surface, where it Is left until it is cold. To remove it, the operator raises the edge of the plaster with the finger tips and pulls it off, quickly. The hairs come with it, and the surface of the skin is left smooth and uninjured. In case of irritation a little olive oil or cold cream may be applied, but it is rarely necessary.

(Ayer, 1901)

This idea was used by others. In 1934, Henrietta A. Fischer was granted a patent for a hair-removing mixture containing synthetic amber – a mixture of musk ambrette and labdanum resin – that could be used as a stick or plaster.

Rosin 5 lbs. Beeswax 1 ib. 4 oz. Synthetic amber 15½ grains to which may be added Oil-soluble red dye ¼ gr. I preparing the mixture, the wax is heated to a temperature preferably between 145°F. and 150°F. A double boiler is convenient for this purpose. When the wax has become melted, the rosin is added in the form of small pieces, a few at a time, while maintaining the melting temperature of the wax.

After the rosin has become melted and mixed with the wax, the synthetic amber is added while stirring the mixture. The stirring is continued until the amber is thoroughly incorporated, and the mixture has become aerated.

The oil soluble red dye is employed primarily for the purpose of giving a flesh-like color to the mixture, and the beeswax employed is preferably white, so that the mixture will be more pleasing to the eye. …

The composition will ordinarily be molded into the form of sticks of various diameters, depending on the areas of the body to be treated … [but] can, of course, be molded into the form of cakes.(US Patent No. 2,062,411, 1924)

Body hair

The primary target for epilating sticks was superfluous facial hair. However, as hemlines rose in the 1920s and bathing costumes exposed more of the arms and legs, more and more women began removing hair from these areas as well. These were larger areas of the body and required a different approach. As well as using chemical depilatories and shaving some turned to removing body hair with various forms of ‘wax plasters’ as the effects were longer lasting.

Hot wax

The most common type of epilating wax plaster would now be referred to as a ‘hot wax’. At their simplest these were made from rosin and beeswax, for example 8 parts rosin to 2 parts beeswax, a formula that bears some resemblance to Unna’s epilating stick. However, most contained other substances as well. They were easy to make as the ingredients were simply heated, mixed together and poured into moulds.

Epilating Wax % Light colored rosin 52.0 Yellow beeswax 25.0 Paraffin 17.0 Petrolatum 5.0 Perfume 1.0 100.0 Melt the rosin and the waxes, mix and add the petrolatum, then when the temperature drops to about 60° C., add the perfume and pour the melted mass into suitable molds. When this wax is used it is melted and painted over the surface to be dehaired.

(Thomsson, 1947, p. 385)

When used, the wax-rosin mixture was warmed, applied to the skin with a wooden spatula or something similar and then removed with a quick action taking the hair with it. Salons usually remelted the used wax, strained it to remove any hair, and then reused it again, making the use of hot wax very cost effective. This practice is not generally considered acceptable today, which is one reason why the use of hot wax in salons has declined.

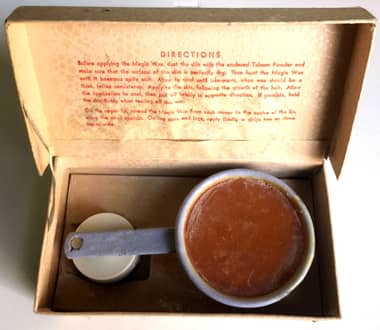

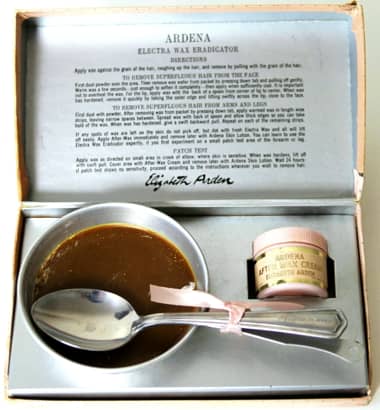

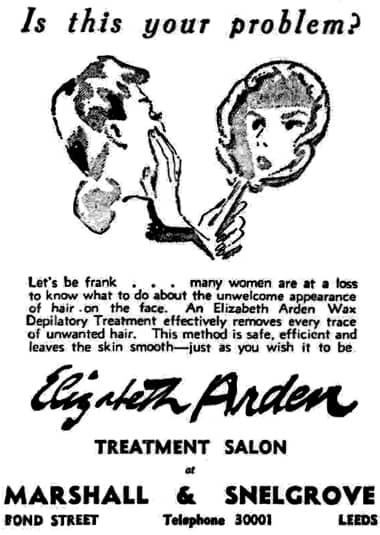

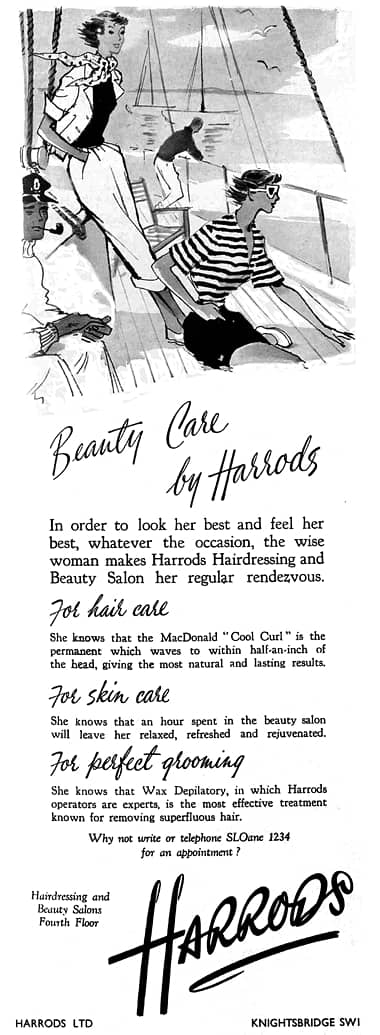

Epilation by hot wax was best done by a professional in a salon but a number of cosmetic companies sold kits for use at home. Both Helena Rubinstein [1871-1965] and Elizabeth Arden [1881-1966] did so and they were not alone. Rubinstein’s kit was called Magic Wax while Arden’s was known by a number of names starting with the Venetian Electra-Eradicator. Both products came with a metal pot to warm the wax, an applicator and a soothing cream applied afterwards to reduce irritation.

Directions

Before applying the Magic Wax, dust the skin with the enclosed Talcum Powder and make sure that the surface of the skin is perfectly dry. Then heat the Magic Wax until it becomes quite soft. Allow to cool until luke-warm, when wax should be a thick, toffee consistency. Apply to the skin, following the growth of the hair. Allow the application to cool, then pull off briskly in opposite direction. If possible hold the skin firmly when tearing off the wax.(Helena Rubinstein Magic Wax box directions)

Using hot wax at home required a good deal of will power and it is easy to see why most women preferred to use a razor or a chemical depilatory, particularly when it came to removing large amounts of auxiliary, leg or arm hair.

See also: Chemical Depilatories

Cool waxes

As mentioned earlier, most rosin or rosin-wax mixtures included other ingredients. This was done to adjust their melting point, flexibility and/or stickiness. Some of these later formulas required little or no heating before they were applied to the skin. The example below is from a patent taken out by William M. Grant in a number of countries between 1937 and 1938:

Epilating Wax Lbs Ozs Honey 72 2 Rosin 20 10 Wax 6 14 Citric acid 1 11 It is desirable that the rosin and wax ingredients be first mixed with one another, namely by the action of heat in a suitable vessel; the honey ingredient is then added gradually, accompanied by slow but continuous stirring, say for 1¼ hours. The citric acid ingredient is then added and the mixture stirred for say, fifteen minutes. The final product is then poured into a mixing machine; and the mixing continued to attain intimate intermixing and until the product has cooled. The final product acquires a creamy texture.

(US patent No. 2,091,313, 1937)

The mixture listed in Grant’s patent did not have to be heated but required a cloth, such as a felted cotton strip, to be pressed down on the applied wax. This was then removed with a quick pull in a manner comparable with modern strip waxes. As the earlier example from Lola Montez shows using some sort of fabric to remove an adhesive mixture was not a new idea but the methods varied. Some formulas required the sticky mixture to be applied to the cloth rather than the skin, an idea used in a lot of commercial products today.

Ounces Rosin 10 Beeswax ⅔ Mineral oil 6 In preparing the product, the rosin is first melted in the oil and then the wax in small pieces is gradually added to the heated mixture. Upon cooling, the mass is of the consistency of a smooth paste. When not perfumed it is practically odorless. …

In using the depilatory [sic], it is spread in a thin layer over a piece of cloth of sufficient size to cover the area of the skin where the hair is to be removed. The cloth should be relatively thin and somewhat stiff and preferably waterproof. The cloth is then firmly applied over the skin where the hair is to be removed with the coated side of the cloth against the skin. A piece of ice is then held against the uncoated surface of the cloth, and in case the ice is not large enough to cover the entire surface, it may be rubbed over the surface. Upon the skin becoming thoroughly chilled through the cloth, which usually takes about one minute, the end of the cloth is grasped in the fingers and the cloth quickly pulled or ripped from the skin.(US patent No. 2,202,829, 1937)

A variety of materials have been used as for the ‘waxing strip’ over the years including calico, celluloid and rayon but many salons now prefer disposable non-stretching paper, an idea that goes back to the 1940s at least. A patent granted to Leonard J. Neary in 1945 recommended using paper in preference to cloth to epilate hair using a syrup made from 2 parts commercial glucose and 1 part zinc oxide mixed with enough water to give the product a suitable consistency.

[The] superior result from using a non-stretching, non-skewing sheet such as paper, compared to the use of a piece of ordinary cloth, appears to be based upon the paper’s freedom from stretching and skewing during the stripping operation.

(US patent No. 2,417,882, 1945)

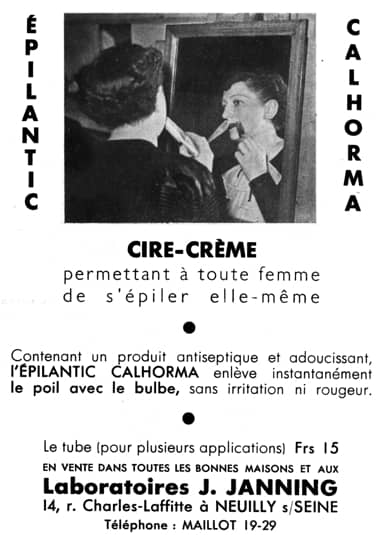

Neary imagined that his invention would be sold in convenient tubes. Others had the same idea. A French brand, Calhorma also packaged their wax epilatory called Cire-Crème in tubes. The tubes were warmed in a water bath before being squeezed out and smoothed across the skin with a spatula.

Above: 1937 Applying warmed Cire-Crème from a tube on the leg of a client in a French salon.

Above: 1937 Removing the cooled Cire-Crème along with the leg hair.

Sugaring

Neary’s patent uses sugar as the hair-binding agent and is a forerunner of the ‘sugaring’ hair-removal treatments that are popular today. These can be made at home using a mixture of sugar, lemon juice and water. The lemon juice is important as it reduces the possibility of the sugar crystallising. Commercial versions would also add a preservative.

Ingredients %w/w Sucose qs 100.00 Glycerin 10.00 Citric acid 0.50 Potassium sorbate 0.15 Methylparaben 0.10 Water (aqua), deionized 5.00 to 15.00 Procedure: A proper vessel is required to heat and maintain high temperature while containing any water loss. The sucrose and glycerin is heated to approximately 110°C and mixed. The remaining ingredients are added and mixed until uniform and clear. The batch is held at this temperature until the poper color is obtained (slight brown). It is then cooled to 85-90°C for filling into the appropriate package.

(O’Lenick & Shea, 2009, p. 813)

Treatment

The method used to remove hair by waxing the body has not changed much over the years but techniques do vary. The description below is from 1961 and is for a hot wax treatment. It suggests using a brush or spatula but the former would not be recommended today for health reasons. Waxing falls under regulations associated with skin penetration that also apply to treatments such as electrolysis and tattooing. The method used to melt the wax is also crude. Most salons today would use an electrical wax pot with a built in heater and thermostat.

A Preparation:

1. Set the vessel containing the wax on a stove or hot plate to melt. When right for use, it should be about the consistency of thick molasses, and register no more than 95-98°F.

2. Wash the area to be treated with a mild soap and warm water; rise thoroughly and dry.

3. Dust the area generously with talcum powder.

B Manipulation:

1. Apply the melted wax with a spatula or brush, spreading it over the skin in a smooth layer about one-half inch thick, following the same direction as the hairs.

2. Allow the wax to cool, and while it is cooling loosen and raise a small corner by which you can remove it.

3. When the covering is cold and hard, stretch the skin near this spot by pulling with the other hand, and quickly pull the wax away against the direction of growth of the hairs.(Modified from Wall, 1961. p. 510)

August 6th 2019

Sources

Ayer, H. H. (1901, October 6). St. Louis Post Dispatch

Barry, R. H. (1957). Depilatories. In E. Sagarin (Ed.). Cosmetics: Science and technology. New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

Cramp, A. J. (Ed.). (1936). Nostrums and quackery and pseudo-medicine (Vol. III). Chicago: American Medical Association.

Jackson, G. T. (1898). A practical treatise on the diseases of the hair and scalp. New York: E. B. Treat & Company.

Jellinek, J. S. (1970). Formulation and function of cosmetics (G. L. Fenton, Trans.). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Kalish. J. (1940). Cosmetic manual 34 depilatories. The Drug and cosmetic industry, 47(2), 148-150.

Montez, L. (1858). The arts of beauty or secrets of a lady’s toilet with hints to gentlemen on the art of fascinating. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald.

Morris, J. (1987). Beauty therapist’s handbook. London: B. T. Banford Limited.

O’Lenick, T & Shea, F. T. (2009). Depilatories and epilatories. In M.L. Schlossman (ed.). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (Vol. II, 4th Ed.). Carol Stream, IL: Allured Publishing Corporation

Poucher, W. A. (1974). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (8th ed., Vol 3). London: Chapman & Hall Ltd.

Reiger, M. M. & Brechner, S. (1975). Depilatories. In M. G. deNavarre (Ed.) The chemistry and manufacture od cosmetics (2nd ed., Vol. IV, pp. 1229-1273). Ontario, FL: Continental Press.

Sequeria, J. H. (1911). Diseases of the skin. London: J & A. Churchill.

Thomssen, B. S. (1947). Modern cosmetics (3rd ed.). New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

The ugly-girl papers; or hints for the toilet. (1874). New York: Harper & Brothers.

Wall, F. E. (1961). The principles and practice of beauty culture (4th ed.). New York: Keystone Publications.

Wells, F. V., & Lubowe, I. I. (1964). Cosmetics and the skin. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

Favus of the scalp in a young child. Usually a severe case of tinea capitus. Epilating the hair from the infected region was once considered an important part of the treatment for this fungal skin disease.

1919 Dearborn Supply Company Phelactine. A cosmetic version of the epilating stick used by dermatologists in the nineteenth century.

1923 DeMiracle, a chemical depilatory. The reference to the ‘sealing wax’ may be referring to a claim made by a maker of an epilating stick.

1924 Madame Berthé Zip Epilator.

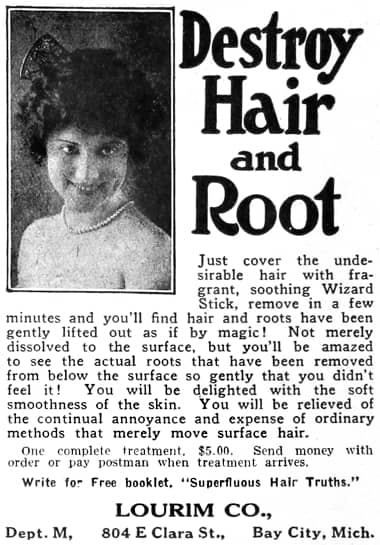

1928 Lourim Wizard Stick.

1931 Gelex Plastique. This product appears to be latex based.

1934 Sadko Wax Depilatory Set.

1935 This French method used a wax covered stick to first spread the wax across the skin in a rolling action and then remove it by rolling the stick back in the opposite direction (‘Les Dimanche,’ 1937).

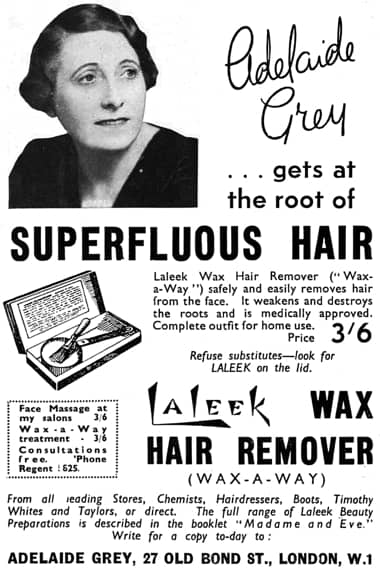

1937 Laleek Wax-A-Way.

Helena Rubinstein Magic Wax kit which included a jar of Pasteurized Face Cream to be applied to sooth the skin after the wax treatment.

Elizabeth Arden Ardena Electra Wax kit containing a jar of Ardena After Wax Cream to be used after the wax treatment.

1937 Calhorma Cire-Crème (France).

1944 Elizabeth Arden Wax Depilatory Treatment (England).

1944 Helena Rubinstein Magic Wax (Australia).

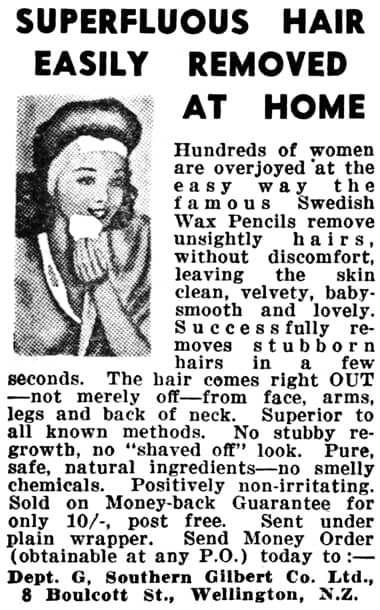

1949 Swedish Wax Pencils (Australia).

1950 Wax Depilatory treatments from Harrods’ salon in Knightsbridge, London.

1953 Industry advertisement for Adelaide Gray Laleek Wax-A-Way and CoolWax. The Coolwax was dispensed from a tube and was easily spread across the skin with a spatula.

1956 Youthexa Hair Remover Stick.

Single wax pot used for strip waxing.

Double wax pot with hair filter used in hot waxing.

1977 Zip-Wax.