Moisturisers

In 1959, the Society of Cosmetic Chemists presented a special award to Dr. Irvin H. Blank of the Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, describing him as the ‘father of moisturizers’.

Blank had summarised his research findings for American cosmetic chemists in the ‘American Perfumer & Aromatics’ in May, 1956. Like his papers in the ‘Journal of Investigative Dermatology’ the 1956 article questioned the belief, long held by many cosmetic chemists and others in the beauty industry, that the main barrier to water loss from the skin was the oils in sebum. Blank demonstrated that it was the moisture content of the outer layer of the skin, the stratum corneum, not oil that kept the skin soft and pliable.

[I]t can be shown that soaking dried cornified epithelium in water or simply allowing it to absorb water from a humid environment will make it flexible. No flexibility has ever been obtained by long immersion of dried cornified epithelium in any type of anhydrous oil or grease. Flexibility is obtained with water, not with oils or greases.

(Blank, 1956, p. 37)

See also: Dry Skin Treatments

The word moisturizer/moisturiser was first applied to skin creams and lotions in the 1950s. Dates vary between etymological dictionaries but all place its appearance after Blank published his article ‘Factors which influence the water content of the stratum corneum’ in 1952.

Blank did not use the term moisturizer in any of his 1950s articles but recommended using two well-known groups of chemicals commonly used in them – occlusives and humectants. Occlusives reduce water loss from the stratum corneum by acting as a barrier to moisture, humectants help the stratum corneum attract and hold on to water.

Since the development of a dry skin is more complex than a simple deficiency of natural oils, a process for the relief of dryness which is directed simply towards the replacement of natural oils may not necessarily accomplish its purpose. The ability of a cosmetic to prevent or relieve dryness appears to be a function primarily of its ability to increase the water content of the stratum corneum. Its oily or lubricating property, per se, does not serve to relieve dryness except in so far as it helps protect the skin and to make the cutaneous surface smoother.

Cosmetics for the relief of dryness should contain either an agent which will form a relatively occlusive, continuous film on the cutaneous surface, thus helping to prevent the loss of water from the skin, or an agent which will help attract water to the stratum corneum from the environment. These cosmetics should be good protectives and not in themselves irritating to the skin.(Blank, 1956, p. 39)

The moisture content of the stratum corneum was later shown to be important for normal skin shedding (insensible desquamation). In an article written for the American magazine ‘Drug and Cosmetic Industry’, in 1959, Otto K. Jacobi, vice president and director of research at Kolmar Laboratories, demonstrated that water was needed for the normal release of dead cells from the skin surface. If this process was hindered by a lack of moisture then the cells would stick together and come off in large clumps or scales rather than individual cells. This would result in the surface roughness characteristic of dry skin. We now know that enzymes are involved in desquamation and these require water to function.

Jacobi’s investigations also indicated that the moisture content of the stratum corneum was dependant on hydroscopic substances present in the stratum corneum. His research team named these the Natural Moisturizing Factor (NMF), later shown to include chemicals such as amino acids, organic acids, urea, and inorganic ions.

Insensible desquamation of small scales of horny cells is constantly taking place and goes largely unnoticed. The flexibility of this layer and the amount of shedding which takes place is largely dependent on the layer’s water content. This, in turn, depends primarily on the quantity of water soluble hydroscopic and surface active materials present. These components of the horny layer may be called collectively “Natural Moisturizing Factor” of the skin or NMF.

(Jacobi, 1959, p. 732)

Jacobi’s research, and investigations that followed, changed the way science viewed the stratum corneum. Long thought to be an inert layer of dead cells it is now regarded as a biologically active structure.

Far from being a dead, inert wrapping, the stratum corneum has turned out to be a remarkably dynamic tissue with a multiplicity of functions which continue to surprise and excite us.

(Kligman, 2005, p. 15)

Formulation

Blank’s research led to the development of the new ‘moisturised creams’ of the 1950s. These were often distinguished from the older dry skin creams by their increased use of humectants but this early distinction disappeared after moisturisers became the standard treatment for dry skin.

A dry skin cream is one that is intended for dry skins. It is generally more rich in emollients than the average skin cream. A moisturized cream is one that contains agents which hold or/and attract moisture to the skin. Among the moisturizing agents are the usual humectants such as glycerol, butylene glycol, sorbitol syrup, the polyethylene glycols of molecular weight about 400 and similar products. Other ingredients, such as the unsaturates, lecithin and lanolin fractions will all help maintain moisture in the skin.

(‘American Perfumer and Aromatics,’ October, 1960, p. 10)

Some of the ingredients used in early moisturisers, such as lanolin, mineral oil, petrolatum, and glycerine had a long history of use while others, such as silicones, only came into play during the decade. Later formulations would stress the need for additional emollients. These may also act as occlusives but their primary function was to smooth down flaky skin to reduce its rough appearance.

Moisturizing Cream % Stearic acid 15.0 Lanolin 5.0 Beeswax 2.0 Mineral oil 20.0 d-Sorbitol (70%) 13.0 Sorbitan trioleate (Arlacel 85) 1.0 Polyoxyethylene sorbitan trioleate (Tween 85) 1.0 Water 43.0 (Klarmann, 1961, p. 37)

Early American moisturisers

The United States was the largest and most technically advanced cosmetic market at the time so was best placed to respond to the findings of Blank’s research. Legislative developments in the late 1930s may also have made the American cosmetic industry particularly receptive to adopting the idea of moisturisation.

In 1938, President Roosevelt [1882-1945] had signed into law the Wheeler-Lea Act, and the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. This legislation put severe constraints on the claims American cosmetic companies could make for their products, forcing them to largely abandon well-established nutritional claims for skin-care cosmetics. Following the passing of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) insisted that names such as skin food or muscle oil were removed from product labels. Similarly, after the Wheeler-Lea Act became law, the Federal Trade Authority (FTC) began issuing cease-and-desist orders stopping companies from making nutritional claims when advertising their cosmetics.

See also: The FDA, FTC and Cosmetics

Blank’s research allowed cosmetic companies to make moisturising claims that were backed by solid scientific research, that were unlikely to be challenged by the FDA or the FTC. It gave the American cosmetic industry a new moisturising metanarrative that largely replaced the older nutritional metanarrative that got many cosmetic companies into trouble with the FDA and the FTC after 1938.

The new moisturising narrative took a while to get established and the 1950s was a transitional period during which American companies and consumers came to terms with the new idea of skin hydration begun by Blank’s research. This development was largely a change in the way skin creams and lotions were marketed rather than a major innovation in formulation. This allows us to get some idea of the transition by examining product advertisements for skin creams during the 1950s.

Some American creams and lotions drew attention to skin dehydration prior to the publication of Blank’s first paper on skin hydration in 1952 but these were referring to hydration deep in the skin not in the stratum corneum. For example, Flowing Velvet Lotion (Jacqueline Cochran, 1949) was advertised as containing an unknown ‘moisture-giving ingredient’ that ‘sinks into your skin’. Attention was also drawn to the importance of oils included in the product.

FLOWING VELVET is a three-way flowing formula with three-way action. This unique combination of rich cream, lotion and facial oil, containing a new moisture giving ingredient, hydrolin, acts on your skin in three ways:

• It furnishes moisture that actually sinks into your skin.

• It supplies necessary oils for essential lubrication.

• It maintains the normal balance of oils and moisture.(Jacqueline Cochran advertisement, 1951)

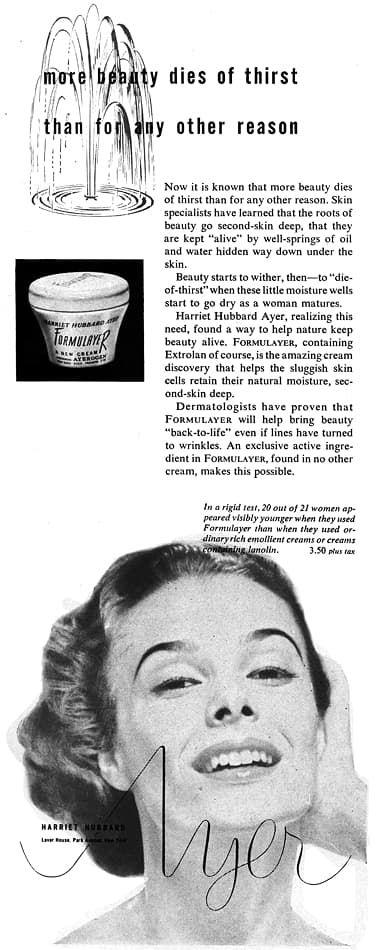

Advertisements for Formulayer Moisture Cream (Harriet Hubbard Ayer, 1950) were also concerned with moisture retention deep in the skin.

FORMULAYER works where beauty begins. When we are very young the small active cells below the skin surface need no help in retaining this beautifying moisture. But, young as we may feel, come our twenties . . . these cells grow lazy and let that all important moisture slip away. Our skin dries, and the first signs of age appear, often prematurely.

FORMULAYER was conceived for just one purpose—to help those cells retain that moisture. For several years Ayer chemists did intensive research into skin chemistry. They discovered that by the use of Ayerogen, an active ingredient exclusive with Ayer (not a hormone) they could achieve this purpose. The result is FORMULAYER.(Harriet Hubbard Ayer advertisement, 1951

Both Flowing Velvet Lotion and Formulayer Moisture Cream were developed as substitutes for hormone beauty creams then widely in use which were thought to increase sub-epidermal skin hydration producing a more youthful-looking complexion.

Skin-care cosmetics introduced after Blank published his findings also found it hard to abandon the idea that it was oils that kept the skin soft and pliable and/or that moisture was needed below the surface of the skin. Act of Beauty (Barbara Gould, 1954) added a ‘rare natural oil’ in addition to a humectant that worked ‘deep beneath the surface’ and Active Moisturizer (Max Factor, 1955) included ‘missing oils’ and also claimed to work below the surface of the skin.

To complicate matters, the introduction of ‘moisturisation’, as suggested by Blank, coincided with the arrival in the American market of a range of new ‘biological’ additives, most coming from developments in Europe. This began in 1954 when three brands – Orlane, Alexandra de Markoff, and Marie Earle – introduced cosmetics containing royal jelly. Royal jelly was followed by other so-called ‘biologicals’ including placental and embryo extracts, which joined pre-war anti-ageing ingredients such as vitamins and hormones.

Also see: Royal Jelly, Placental Creams and Serums, Vitamin Creams, and Hormone Creams, Oils and Serums

Adding these novel ingredients to skin creams and lotions improved sales figures for skin creams and enabled American companies to charge higher prices for them.

An extremely pleasant aspect of the sales increase in creams is the profit margin it brings to manufacturers. It is now generally recognized that these cosmetic creams of the newer type selling for $5.00 and over are bringing much greater net profit to the manufacturer than does perfume. In other words, the highest mark-up of a cost in the cosmetic industry.

(Drug and Cosmetic Industry, 1959, p. 322)

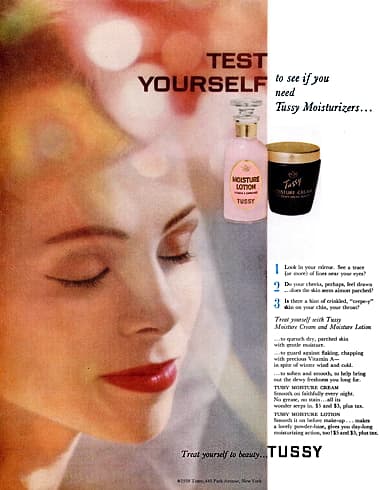

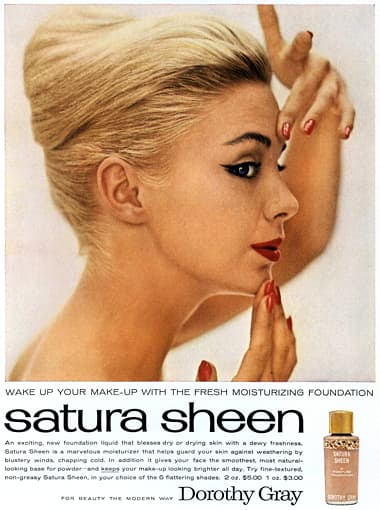

These new biological additives helped revitalise the American skin-cream market but their inclusion often meant that moisturising claims were relegated to a secondary position. In some cases, these biological additives also claimed to be moisturising. For example, Satura Moisturizing Cream (Dorothy Gray, 1953) was formulated with hormones to maintain ‘inner moisture’ as well as skin softeners, and emollient oils. Liquid Treasure (Richard Hudnut, 1954), Vitamin Moisture Balancer (Coty, 1956), Moisture Lotion (Tussy, 1957), and Super-Moist Beauty Emulsion (Germaine Monteil, 1958), all included vitamins in their formulation, often suggesting that these were the source of ‘inner moisture’. Coty went further, suggesting that surface moisturisation was not enough.

Science discovers it isn’t enough to moisturize your skin from the outside in. The only moisture treatment that can really help to beautify your skin must come naturally, from within. And now a way has been found to replenish and regulate this vital supply to inner moisture.

The secret is vitamins. Science now knows that certain vitamins patted directly into the skin penetrate deep down to nourish and act like a fountain of youth, to plump out dried-up skin, soften, freshen, smooth.(Coty advertisement, 1956)

Other additives introduced in the 1950s were also advertised as having moisturising capabilities. For example, the placental extract used in Moisture Petals (Du Barry, 1958) was said to increase the flow of natural oils as well as moisture, again suggesting that oils were needed as skin softeners.

[I]t has astonishing power to penetrate to the cellular layer of your skin. Instantly it starts to increase the flow of natural oils and moisture—coaxing in a radiant bloom and freshness—helping to banish that drying look that dulls and coarsens your complexion.

(Du Barry advertisement, 1958)

All these advertising claims are a reflection of the beauty industry’s desire to promote the idea that their skin creams and lotions work deep in the skin, something that is still included in many cosmetic advertisements today.

During the 1960s, the idea of moisturisation became widely accepted by consumers, becoming the main benefit expected from many skin-care cosmetics. In addition to advertisements put out by cosmetic companies, this was helped by the numerous articles written about moisturisation, such as the one below from the ‘Ladies Home Journal’ (1962). These articles provided valuable information on the benefits of moisturisers, even if some of their rationalisations were faulty.

Our skin is a multilayered organ. The top layer is called the stratum corneum, or horny layer, and it is this visible surface layer that reports via your mirror as to the state of your skin’s health. Whether your complexion is reflected as firm or lined, smooth or flaky, depends chiefly on the maintenance of the proper amount of moisture held in this surface layer. Beneath the horny layer is the dermis, which functions as the supply center for your skin. In it are the sebaceous glands that supply sebum, the skin’s own natural lubricant, and the eccrine glands that supply moisture.

Nature’s formula is such that these oils and moisture can combine, forming a thin emulsion that rides on the surface of the skin, serving to both lubricate and maintain surface moisture. As this film is constantly being evaporated off the skin’s surface into the surrounding air, it is also being constantly replenished from beneath.

However—and this is the reason for moisturizing preparations—this seemingly perpetual balance between evaporation and replacement of moisture can be upset. It happens as one gets older (skin begins to “age” at 25) and the oil and moisture glands slow down their production, and it also occurs when there is a lack of water-binding material in the outer layer of the skin. This permits moisture to be evaporated at the surface more quickly than it can be replaced. These two are natural causes for moisture losses. The other causes are as close and as ordinary as the air we live in, which can and does dehydrate your skin.(‘not just cream—Humidity!,’ 1962, p. 26)

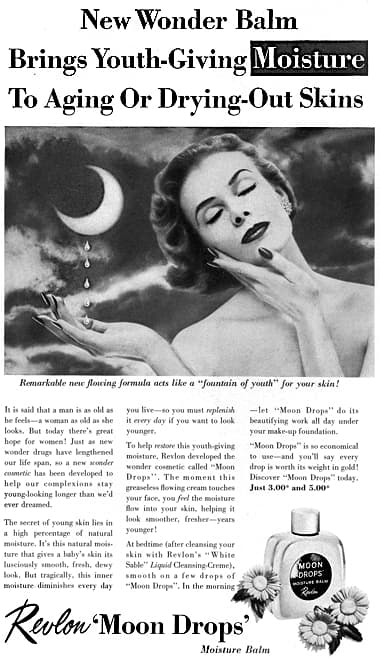

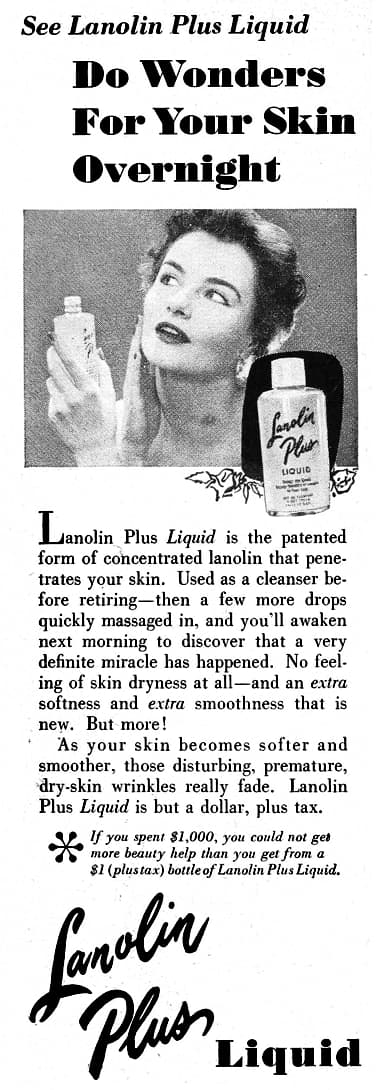

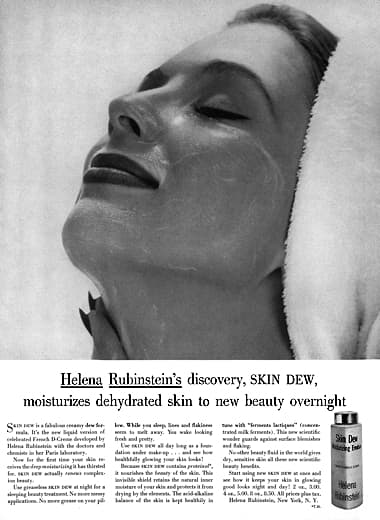

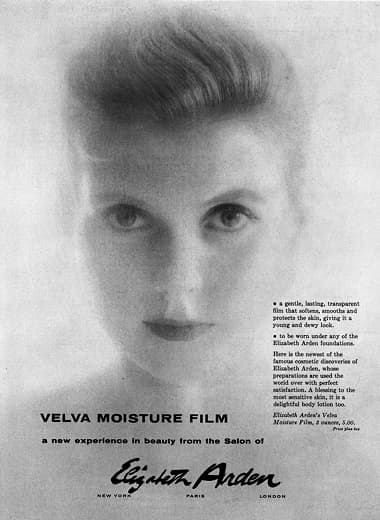

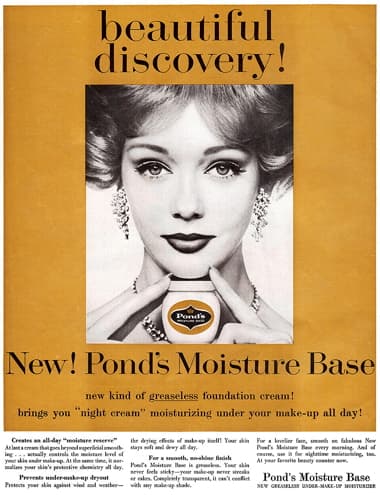

Included in the ‘Ladies Home Journal’ article was a list of American skin-care cosmetics the magazine considered to be moisturisers. Some were relatively new but others had existed before 1952. Listed items were: Deep Mist (Almay); Velva Moisture Film (Elizabeth Arden); Moisture Lotion (Ar-Ex); Creme Supreme (for dry skin), and Dew Kiss (Avon); Formulayer Moisture Cream, and Formulayer Moisture Lotion (Harriet Hubbard Ayer); Fountain of Beauty (Beauty Counselor); Moisture Lotion (Bonnie Bell); Revenescence Lotion, Revenescence Cream, and Velo-Derma 770 Lotion (for dry and mature skin) Charles of the Ritz); Flowing Velvet (Jacqueline Cochran); Vitamin Moisture Balancer (for dry and normal skin), and Vitamin Moisture Balancer (for oily skin); Moisture Petals (Du Barry); Multilayer Moisturizer (Frances Denney); Cup of Youth (Max Factor); Secret of the Sea Emulsion, Satura—Vitamin A (for dry skin), and Satura—Vitamin A and Hormones (for dry and mature skin); Act of Beauty (Barbara Gould); Moisture Cream (Andrew Jergens); Lanolin Plus Liquid (Lanolin Plus); Estoderme Youth Dew (Estée Lauder); Moisture Creme (Marcelle); Alexana (Alexandra de Markoff); Polyderm Moisturizing Lotion (for dry Skin) (Prince Matchabelli); Super Moist Beauty Emulsion (Germaine Monteil); Aqua-Lube (Merle Norman); Moisture Base (Pond’s); Moisture Control (John Robert Powers); Moon Drops foundation, and Moon Drops Moisture Balm (for dry skin) (Revlon); Skin Dew, Skin Dew Night Cream, and Herbessence Skin Life Emulsion (Helena Rubinstein); Artesian (Scandia); Deep Magic Dry Skin Conditioner (Toni); Moisture Lotion, and Moisture Cream (Tussy); and Velvet Skin Moisturizer (Yardley).

The extensive nature of this list, which does not include the wide range of moisturising cleansers, masks and make-up products that were also available by then, is a good indication of how all-encompassing the concept of moisturisation had become within the beauty industry.

First Posted: 30th August 2022

Last Update: 3rd March 2023

Sources

Blank, I. H. (1952). Factors which influence the water content of the stratum corneum. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 18(6), 433-440.

Blank, I. H. (1953). Further observations on factors which influence the water content of the stratum corneum. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 21(4), 259-271.

Blank, I. H. & Shappirio, E. B. (1955). The water content of the stratum corneum. III. Effect of previous contact with aqueous solutions of soaps and detergents. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 25(6), 391-401.

Blank, I. H. (1956). Mechanism of the action of agents used for the relief of dry skin. American Perfumer & Aromatics. May, 67(5), 35-39.

Drug and Cosmetic Industry. (1959). March, 84(3) pp. 322, 334.

Jacobi, O K. (1959). Moisture regulation in the skin. Drug and Cosmetic Industry. June, 81(6), 732-734, 810-812.

Klarmann, E. G. (1962). Cosmetic chemistry for dermatologists. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Kligman, A. M. (1963). The uses of sebum. In W. Montagna, R. A. Ellis, & A F. Silver (Eds.), Advances in the biology of skin. Volume IV. The sebaceous glands (pp. 110-124). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Kligman, A. M. (2005). A brief history of how the dead stratum corneum became alive. In P. M. Elias, & K. R. Fiengold (Eds.). Skin Barrier (pp. 15-31). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Kromayer, E. (1930). The cosmetic treatment of skin complaints with special reference to physical therapy and scarless methods of operation. London: Oxford University Press.

Laden, K. (1967). Natural moisturising factors in skin. American Perfumer & Cosmetics. October, 82(10), 77-79.

not just cream—Humidity!. (1962). Ladies Home Journal, October, 79(9), pp. 26, 117.

Irvin H. Blank [1902-2000].

Otto K. Jacobi [1914-1977].

1951 Jaqueline Cochran Flowing Velvet.

1953 Harriet Hubbard Ayer Formulayer.

1953 Revlon Moon Drops.

1954 Lanolin Plus Liquid.

1956 Helena Rubinstein Skin Dew.

1956 Elizabeth Arden Velva Moisture Film.

1957 Shulton Desert Flower Beauty Cream.

1958 Tussy Moisture Lotion and Moisture Cream.

1958 Dorothy Gray Satura Sheen Moisturizing Foundation.

1959 Pond’s Moisture Base.

1959 Lanolin Plus Liquid moisturizer.

1960 Prince Matchabelli Polyderm.

1966 Frances Denney Multi-Layer Moisturizer and Lip Moisturizer.