Diathermy

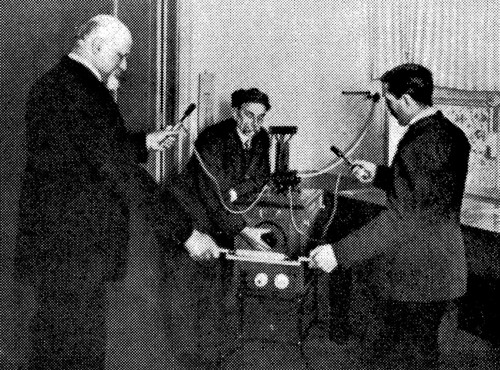

The story of diathermy began in 1892 when Doctor Jacques Arsène d’Arsonval demonstrated that a high-frequency electric current could pass through a person’s body without electrocuting them, the only sensation being that of warmth (Cumberbatch, 1937, p. 13).

Further experiments by d’Arsonval and others led to the use of high frequency currents to heat up body tissues. Heat treatments – using such things as hot bricks, poultices, hot water and sunshine – had been used in medicine treatments for centuries but none of these previous practices delivered heat as deeply.

Above: D’Arsonval (centre) demonstrating the lack of sensation when passing a high-frequency current through the body sufficient to light an incandescent lamp.

Although d’Arsonval introduced the idea, it was the German physician, Karl Franz Nagelschmidt who did the most to get it accepted in medical circles. In 1908, he demonstrated the deep-heating effect of high-frequency currents using a machine of his own devising, coined the term diathermy, and then published a book on the subject in 1913 (‘Lehrbuch der Diathermie’), after which diathermy became an increasingly popular in the treatment of arthritis and other inflammatory conditions, and for pain relief.

Heat and high frequency

The heating effects of high-frequency currents were clearly observable but there was some conjecture over how the heat was generated.

This current also increases bodily heat, almost always showing a rise of from half a degree to a degree and a half in a ten-minute application. Some attribute the effect of this current to the heat it develops in the tissues. In my opinion its principal effects are due to “cellular massage.”

… The effect of auto-condensation in producing cellular massage is appreciated when we realize that the charge in the patient’s body must return back into the circuit and then alternate with one of opposite polarity, thus, first a positive and then a negative charge is carried into the body and back again. This produces a to-and-from wave that acts upon every cell in the organism.(Eberhart, 1911, pp. 68-69)

The principle behind the heating effect of high-frequency currents is better understood today. We now regard temperature as a measure of the average kinetic energy (energy of motion) of the molecules in a substance, so anything that increases the movement of the molecules in that substance will raise its temperature.

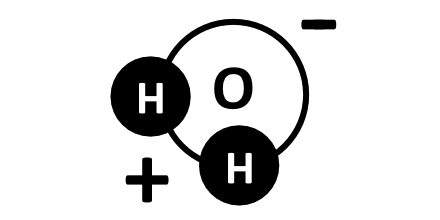

Since electrical fields have a charge they have the potential to affect other charged particles, particularly polar molecules like water that vary in charge from one side of the molecule to the other.

Above: Water molecules are made of two atoms of hydrogen (H) and one atom of oxygen (O). Water is a dipole; that is, one side has a slight positive charge while the other is slightly negative. This means that it is affected by the pushing and pulling forces of electrical fields following the electrical principle that like charges repel and unlike charges attract.

If the electrical current is direct (galvanic) the molecules will align themselves with the electrical field so that their positive pole is towards the negative electrode and their negative pole is towards the positive. However, if the electrical field is constantly oscillating, as it does in a high-frequency alternating current, these polar molecules will be continuously rotated as they realign themselves with the changing polarity of the electrical field. This will cause the molecules to vibrate rapidly and produce a rise in temperature.

The effects of high-frequency currents on body tissue will depend on the amount of heat generated. At first, the tissue will be warmed but if higher temperatures are reached electrocoagulation will take place, as the proteins in the tissue denature and harden – as happens to egg white when it is cooked. If enough heat is applied, the water in the tissue may boil off resulting in electrodessication.

The medical profession generally refers to diathermy that generates heat intense enough to desiccate or coagulate body tissues – used in surgery as an alternative to a knife or scalpel – as ‘surgical diathermy’ to distinguish it from ‘medical diathermy’ which gently warms the tissues rather than destroying them. This type of diathermy employs larger electrodes so that the heat is spread over a wider area.

Surgical diathermy: desiccates or coagulates body tissues.

Medical diathermy: warms body tissues.

Diathermy in Beauty Culture

When the term diathermy is used in Beauty Culture it usually refers to ‘surgical diathermy’. Diathermy treatments of this type – also known a thermolysis – were used from the 1930s onwards in Beauty Culture as an alternative to electrolysis for the permanent removal of superfluous hair, spider veins (telangiectasia), acne, warts, moles and other skin blemishes.

See also: Electrolysis and Thermolysis and the Blend

High-frequency currents have also been used in beauty treatments to warm the face and body as with ‘medical diathermy’. The first use of diathermy in this manner in Beauty Culture, that I know of, was Elizabeth Arden’s Vienna Youth Mask. Introduced in 1928, it was claimed to have a rejuvenating effect by stimulating the circulation of blood through the facial tissues.

See also: Arden Vienna Youth Mask

Other salons followed Arden’s lead and facial treatments incorporating diathermal heat became quite common in the 1930s, in part because the machines could also be used to remove hair through thermolysis.

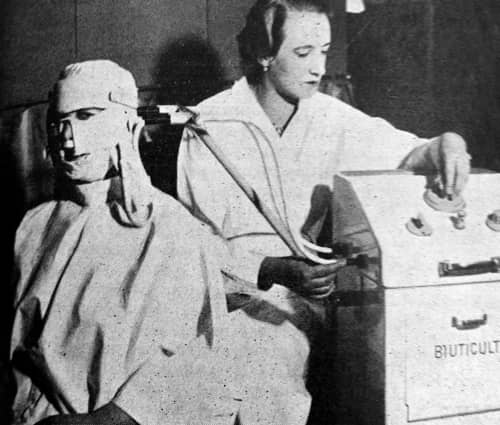

Above: 1936 Silk mask and electrode method.

Treatment begins by cleansing the face, which is then dried with tissue and the mask applied. The chin electrode is first fixed in place by an adjustable rubber strap. In similar manner, double cheek electrode bands and the forehead electrode band is fixed. The cables, which are heavily insulated, are then attached and circuits closed. The resulting sensation is a pleasant, deep-reaching warmth; the consequence of a 10 minutes controlled application is a thorough enduring stimulation of skin and sub-cutaneous tissues. This intensive stimulus is not to be achieved by massage, or any available lotion, and is under full control of the operator.

(The Hairdresser and Beauty Trade, 1936)

Mention should also be made of indirect high-frequency treatments, also known as a Viennese massage. These combined a facial massage with a high-frequency current to heat the skin under the therapist’s fingers.

See also: High Frequency

Although there are some salons today that offer warming diathermy treatments as a ‘circulation booster’ during a facial, these are not typical. A more common and more recent use of ‘medical diathermy’ in Beauty Culture has been in cellulite treatments. Although it is generally combined with other procedures rather than used in isolation, the deep heat produced by diathermy has been claimed to enhance collagen production; increase blood circulation through vasodilation; improve lymphatic drainage of trapped fatty deposits; and even break down fat cells.

Updated: 23rd July 2018

Sources

Eberhart, N. M. (1911). A working manual of high frequency currents. Chicago: New Medicine Publishing Company.

Guy, A. W. (2011). Biological effects of electromagnetic radiation. Retrieved December 12, 2014, from

http://www.ieeeghn.org/wiki/index.php/Biological_Effects_of_Electromagnetic_Radiation

Cumberbatch, E. P. (1937). Diathermy including diathermotherapy and other forms of medical and surgical electrothermic treatment (3rd ed.). Great Britain: William Heinemann (Medical Books) Ltd.

The Hairdresser and Beauty Trade. (1936). August 14, VII(24), p. 47.

Jacques-Arsène d’Arsonval [1851-1940].

Karl Franz Nagelschmidt [1875-1952].

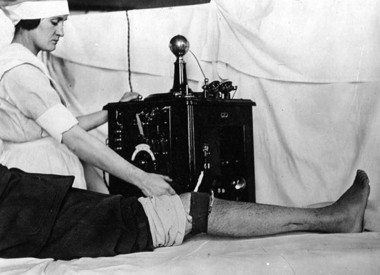

Nurse administering a diathermy treatment for the knee (First World War).

Diathermy unit for home use.

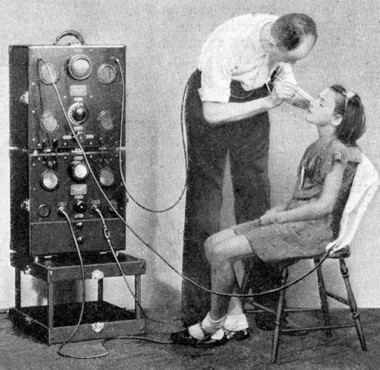

1930 A man having a diathermy heat treatment on the frontal cortex of his brain.

1933 Surgical diathermy treatment, possibly for pimples or acne.

High-frequency diathermy could be replaced with a simple heating pad. This mask appears to be a Thera Therm Electro-Velour face mask. Introduced around 1938, it was operated by an adjustable heating pad, similar to those used in electric blankets.

Coin-operated diathermy machine.

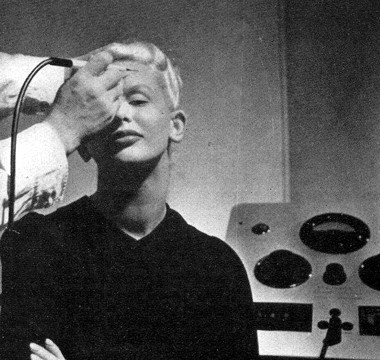

1939 Surgical diathermy treatment to coagulate acne pustules, although the model in this photograph does not look like she has an acne problem.

1954 Diathermy machine used in the medical treatment of sciatica.