Elcaya

The origins of Elcaya – pronounced El-ki-ya – are generally credited to the Canadian James C. Crane who began selling Elcaya in Fulton Street, New York in 1901 starting with just US$4.50. Below is a typical report of his rags to riches story.

After about two years in Toronto his [James Crane’s] ambitions led him to try his luck in the great metropolis of New York, and he began his career there as a detail man, canvassing the physicians of the United States for a New York firm. This was in the fall of 1895, and it was while calling on the physicians in Buffalo in 1900, at the time of the Pan-American Exposition, that he gained a hint of making a toilet cream from Dr. Roswell Park, the surgeon who later attended President McKinley after he was shot by Czolgosz. Mr. Crane began marketing his product, which he called Creme Elcaya, in a most humble way in a little office on Fulton Street in New York, with a cash capital of $4.50. Creme Elcaya was such a novelty in the way of toilet creams that its success was instantaneous, and its world-wide sale today attests the superior quality of the product itself, and the method of marketing employed has gained the confidence of the trade.

(“Canadian’s success in the United States,” 1920)

Some of the details in this tale are incorrect – the Pan-American Exposition was in 1901 rather than 1900 and Dr. Roswell Park [1852-1914] did not operate on President McKinley after he was shot. In addition, the story of Crane and the beginnings of Elcaya leaves out a lot of the backstory.

James C. Crane

James Crane was born in Aylmer, a town in Elgin County, Ontario, Canada. He began his working life as a drug clerk graduating from the Ontario College of Pharmacy in 1892. He worked for a time at John Lewis, a chemist in Montreal, but moved to New York in 1895. There, as the story above mentions, he got a job as a sales representative for a drug firm, the company being Cassabeer Pharmacal. Cassebeer had established a factory to make proprietary lines on Long Island in 1894 so were looking for salesmen when Crane arrived in New York in 1895.

Crane was still working for Cassebeer when he began acting as the sole agent for Crême Elcaya in 1901. His office in the Downing Building at 108 Fulton Street, New York was also located in the same building as Cassabeer Pharmacal and it was Cassabeer Pharmacal that trademarked Elcaya in 1904. So, although Crane can probably take credit for much of the success of Elcaya, the idea that he started out alone with just US$4.50 seems to be a fabrication.

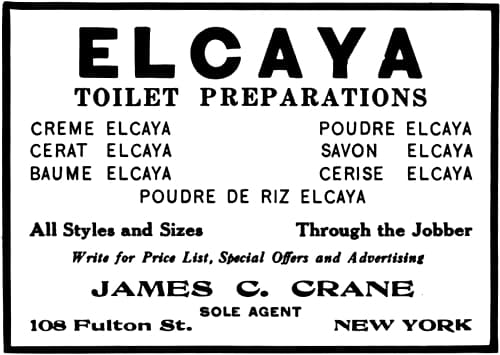

Products

Cassebeer Pharmacal’s initial Elcaya products were Crême Elcaya and Elcaya Witch Hazel Cream. The name was taken from the Elcaya tree, an undescribed plant from Yemen that was noted for its perfume.

Above: 1902 Cassebeer Pharmacal proprietary lines including Creme Elcaya and Elcaya Witch Hazel Cream.

Crême Elcaya: “[A]n exquisite toilet cream, delightful, fragrant and beautifying. Original in character and odor.”

Elcaya Witch Hazel Cream: “[I]s healing, soothing and refreshing.”

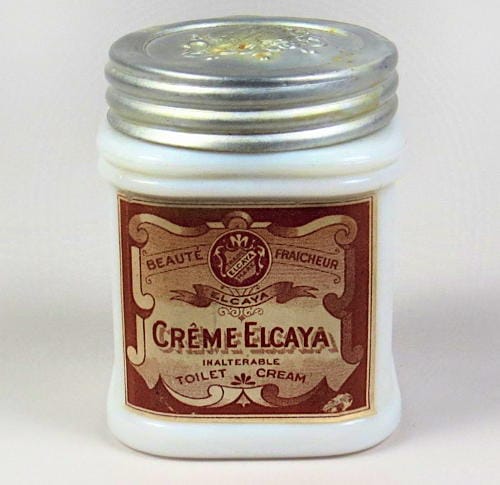

Above: Crême Elcaya (Smithsonian).

Crême Elcaya appears to have been a stearate cream. It predates Pond’s Extract Vanishing Cream (1904) and may have been the first ‘vanishing’ cream manufactured in the United States. However, it was not the first cream of this type. That accolade goes to Burroughs Wellcome’s Hazeline Snow (1892).

See also: Vanishing Creams and Pond’s Extract Company

Unlike cold creams, Crême Elcaya had a matt, non-greasy finish which made it attractive as a day cream and/or a base for face powder. However, this was not the only reason for its success. Like others, Crane imposed a rigid price maintenance policy when selling his goods which stopped price cutting, making it more attractive to small drug store owners competing with large chain stores. This strategy was also followed by Carl Weeks [1876-1962] with his Armand range.

Above: 1911 Crême Elcaya – Sold under restricted conditions.

Price maintenance with me has not been a fad nor feature, nor has it been undertaken to secure business. After some years of successful business some of the firms with whom I had enjoyed such pleasant relations informed me that competitive firms (to whom I did not sell) were retailing Creme Elcaya at 39 cents, and that unless I stopped this cutting they would cut out the goods. I immediately began to ascertain where the cutters were getting their goods, and then to figure out how to stop the cutting. I found there was only one way—to fill every order myself—and this I did, much as such an undertaking meant. I turned down during 1906 orders for more than a gross a day every day in the year, and no one got the goods unless he agreed without reservation to sell at 50 cents.

(‘Successful present day methods of enforcing price protection,’ 1911)

See also: Armand

This does not mean that Elcaya was not sold in department stores. On the contrary, Crane was very determined to get Elcaya on their shelves as this would improve its cachet. His first customer in New York was B. Altman & Co.

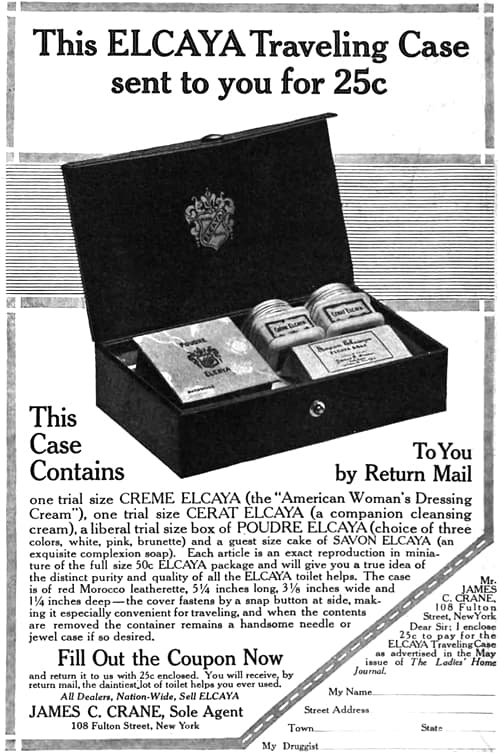

By the end of the decade a number of additional Elcaya products had been added to the range – a cleanser, soap and face powder.

Cerat Elcaya: “[P]articularly prepared for cleansing and softening the skin.”

Savon Elcaya: “[A] perfectly saponified Olive Oil Soap of uncommon purity and having the exquisite ELCAYA odor.”

Poudre Elcaya: “[V]ery fine and adherent, giving the skin a natural appearance and the ELCAYA fragrance.” Shades: White, Pink, and Brunette.

Above: 1913 Elcaya Traveling Case containing Poudre Elcaya, Creme Elcaya, Cerat Elcaya, and Savon Elcaya.

Further products were added in the years leading up to America’s entry into the First World War. These included Elcaya Rice Powder, a talcum powder in scented and unscented versions, and Cerise Elcaya Rouge.

Above: 1915 Elcaya Toilet Preparations.

Expansion

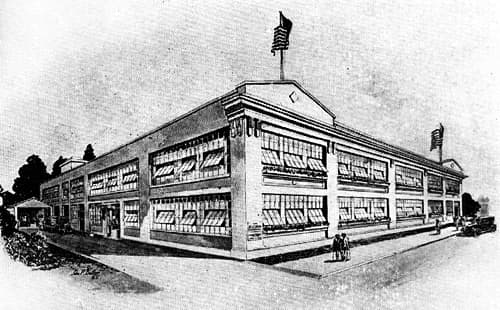

The success of the Elcaya range led to the founding of the Elcaya Company, Inc. (capital US$300,000) in 1915, a move to new headquarters in the Remsen Building at 148 Madison Avenue in 1917, and the establishment of a factory and laboratory on the corner of 1st Street and Freeman Avenue, Long Island in 1920.

Above: Elcaya factory in Long Island.

Elcaya products had been available in Canada from 1904 at the latest and a separate company – the Elcaya Company of Canada Ltd. – was founded in Montreal (capital CA$10,000) in 1919 with a factory built in Aylmer, Ontaria – Crane’s hometown – in 1921.

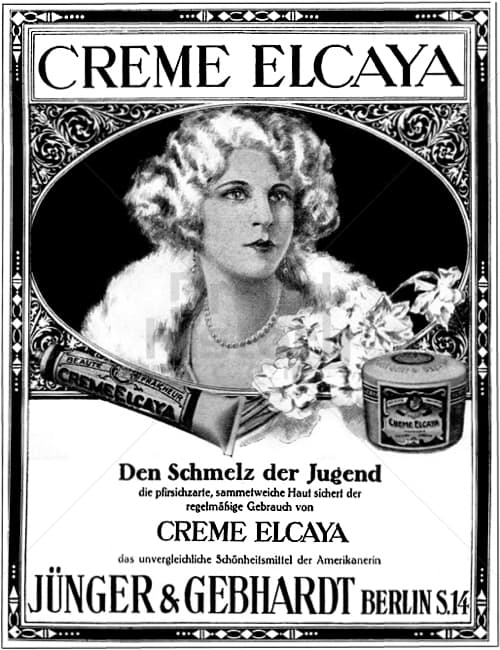

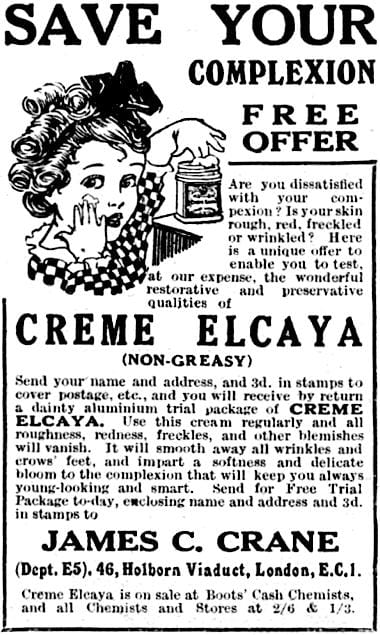

Overseas markets were also opened. Elcaya was being sold in Britain no later than 1904 through a depot at 46 Holborn Viaduct, London and then later through a series of London agents. In France, Elcaya was available from Roberts & Co. who ran the Pharmacie Anglais at 5 Rue de la Paix, Paris. It became widely available across Europe and in places such as Australia and The Philippines after the First World War.

Above: 1926 Creme Elcaya (Berlin).

Northam Warren

James Crane’s health had been failing and he retired in early 1924. In February, 1924, Hugh MacBride assumed control of the company through the purchase of the common stock and became its new president. Born and educated in Boston, MacBride had been previously working as treasurer and director for the cosmetic company, V. Vivaudou.

MacBride does not appear to have controlled the company for long as Elcaya, Inc. and Elcaya Canada Ltd. were bought by Northam Warren – the makers of Cutex – in 1926. Northam Warren [1878-1962] became the new company president and the New York office of Elcaya was moved to the Cutex Building at 114 West 17th Street.

See also: Northam Warren

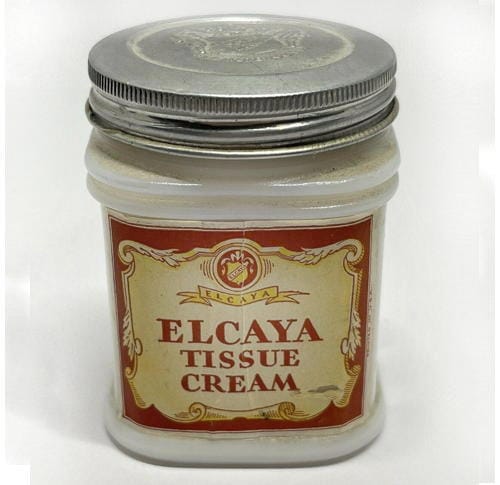

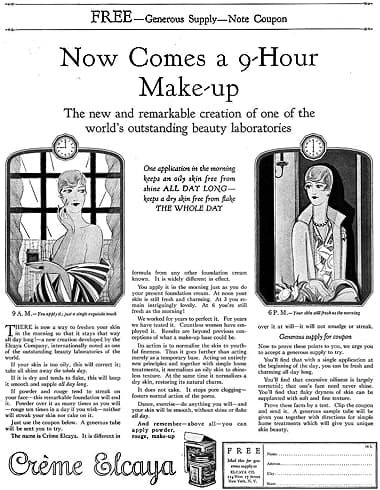

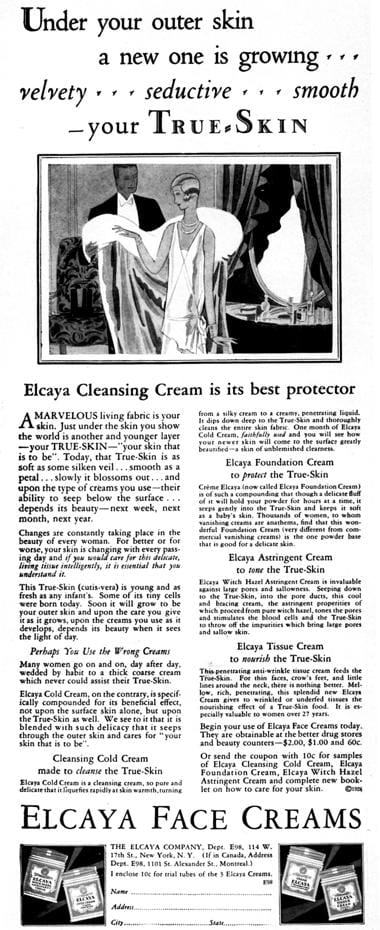

After a substantial review of the range, Northam Warren decided to limit the line to four related skin creams but planned to add a face powder at a later date. In 1927, the labels and cartons of these creams were standardised and descriptive names were added to make their function clear. Crême Elcaya became Crème Elcaya Foundation, Cerate Elcaya was renamed Elcaya Cold Cream, Elcaya Witch Hazel Cream was rebranded Elcaya Witch Hazel Astringent Cream, and a new product, Elcaya Tissue Cream, was added.

Above: 1928 Elcaya repackaged.

Elcaya Cold Cream: “[A] cleansing cream, so pure and delicate that it liquefies rapidly at skin warmth, turning from, a silky cream to a creamy penetrating liquid.”

Elcaya Foundation Cream: “Crème Elcaya (now called Elcaya fFoundation Cream) is of such compounding that through a delicate fluff of it will hold your powder for hours at a time, it seeps gently into the True-Skin and keeps it soft as a baby’s skin”

Elcaya Astringent Cream: “[I]s invaluable against large pores and sallowness. Seeping down …into the pore ducts, this cool and bracing cream, the astringent properties of which proceed from pure withch hazel, tones the pores and stimulates the blood cells … to throw off the impurities which bring large pores and sallow skin”

Elcaya Tissue Cream: “This penetrating anti-wrinkle tissue cream feeds the True-Skin. for thin faces, crow’s feet, and little lines around the neck there is nothing better.”

Above: Elcaya Tissue Cream.

Despite the repackaging and an extensive advertising campaign, Northam Warren appears to have had only limited success in reviving the brand. In 1938, now under increasing pressure from Revlon, Northam Warren sold the American parts of Elcaya and Glazo to Louis William Halk [1882-1945], a previous vice-president of Northam Warren and the two brands were combined to form Glazo, Inc.

See also: Glazo

Halk does not appear to have any success in reviving the brand in the United States. The Second World War disrupted supplies in the early 1940s and although Elcaya products continued to be sold in Europe after 1945 it was in terminal decline and disappears sometime in the 1960s.

Timeline

| 1901 | New Products: Crême Elcaya; and Elcaya Witch Hazel Creme. |

| 1915 | Elcaya Company, Inc, incorporates in New York. Crême Elcaya now sold in tubes as well as jars. |

| 1917 | Offices moved to Madison Avenue. |

| 1919 | Elcaya Company of Canada Ltd. founded. |

| 1920 | Factory built in Long Island. |

| 1921 | Canadian factory built in Aylmer, Ontaria. |

| 1924 | Elcaya acquired by H. C. MacBride. |

| 1925 | Office and factory moved to 116-120 East 27th Street. British agents transferred from Quelch & Gambles Ltd. to A. F. Bayford & Co. |

| 1926 | Elcaya acquired by Northam Warren. |

| 1927 | Elcaya containers updated. New Products: Elcaya Tissue Cream. |

| 1938 | Glazo, Inc. formed from the purchase of Glazo and Elcaya from Northam Warren. |

First Posted: 16th September 2016

Last Update: 28th February 2024

Sources

The American perfumer & essential oil review. (1906-1955). New York: Robbins Perfumer Co. [etc.]

Canadian’s success in the United States. (1920, February 10) The Daily Colonist, p. 4.

Johnson, R. W. (1921). A national business that grew from a capital of $4.50. Printers Ink, 3(4), 39, 80, 83.

Successful present day methods of enforcing price protection. The Pharmaceutical Era, (1911), 44(2), 124.

James Clayton Crane [1870-1952].

1895 Downing Building at 106-108 Fulton Street, New York. The sign has been added to the photograph.

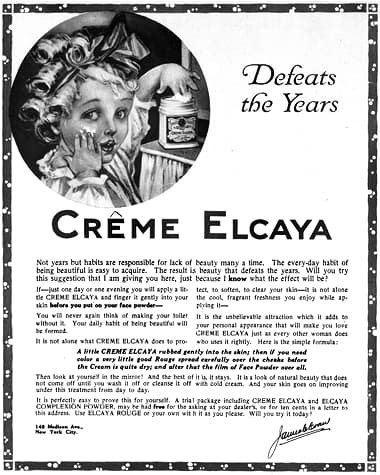

1909 Crême Elcaya.

1910 Crême Elcaya.

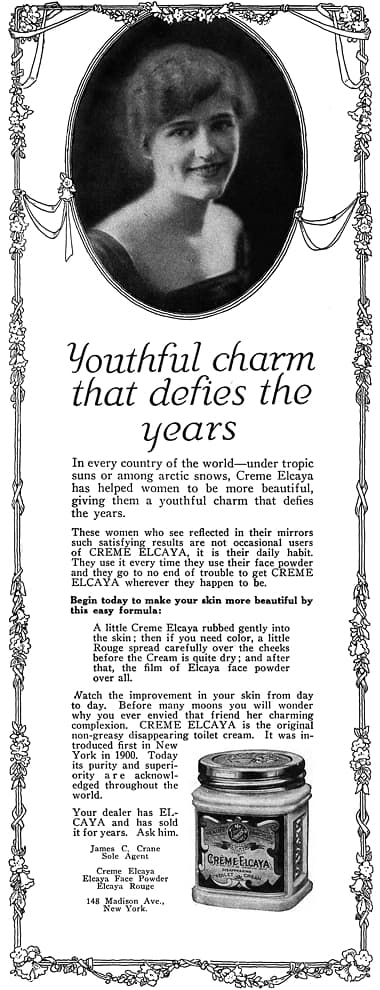

1911 Crême Elcaya (Britain).

1912 Poudre Elcaya.

1913 Elcaya Rice Powder (Poudre de Rz).

1918 Remsen Building on the corner of Madison Avenue and 32nd Street, New York.

1918 Crême Elcaya.

1920 Crème Elcaya.

1920 Crème Elcaya (Britain).

Hugh Clarence MacBride [1891-1971]

1926 Creème Elcaya.

1928 Elcaya face creams.

1940 Creme Elcaya (Germany) in new packaging.