Paraffin Wax Treatments

Physical therapists use heat to relieve disorders like rheumatism and arthritis and make tissue more ‘pliable’ before it is massaged, stretched or otherwise manipulated. During the First World War, a new heat treatment was introduced that immersed all or parts of the body in melted paraffin wax. Although it was messier and more costly than a simple bath of hot water, it was rapidly adopted by physical therapists because it had some advantages over water alone.

Advantages

The most important advantage paraffin had over water was in the way that it retained and conducted heat. If you immerse your hand in a hot water and a paraffin bath of the same temperature, the water bath feels hotter than the paraffin bath. As well as feeling more comfortable, the coat of wax also acts like a blanket trapping the heat at the surface of the skin. Using paraffin instead of water also avoids the shrivelled appearance skin gets after being immersed for a long period in a water bath, so the skin is in a much better condition for any subsequent massage.

Origins

Paraffin wax treatments began during the First World War when the French physician Edmond Barthe de Sandfort [1853-1918] developed a burn treatment he referred to as ‘keritherapy’. This used a patented preparation called ‘ambrine’ – which was widely believed to be made from paraffin wax and oil of amber resin.

Above: Applying ambrine to a burn (Delorme, 1919, p. 165)

The treatment appeared to be effective but as the composition of ‘ambrine’ was patented, other surgeons came up with their own formulae. The best known, called No. 7 paraffin, was made from hard paraffin (67%), soft paraffin (25%), olive oil (5%), eucalyptus oil (2%) and resorcin (1%) (British Journal of Nursing, 1917, p. 167).

As well as being used to treat burns, paraffin was also found to be helpful for rheumatism, joint pain, and other assorted skin complaints so by the end of the war medical treatments that covered part or all of the body in paraffin wax had become common.

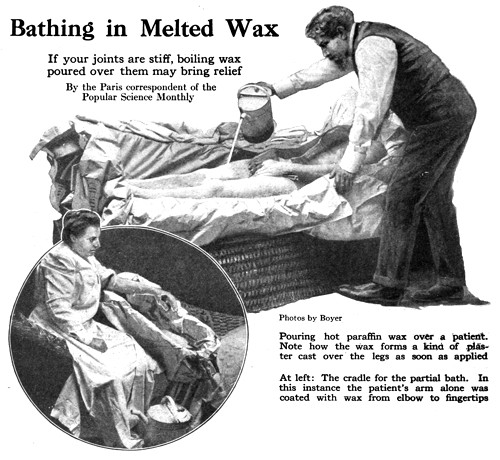

Above: 1917 Part of a Popular Science article on paraffin wax treatments (Bathing in melted wax, 1917, p. 578).

The wax bath is a new idea in medicine and is recommended as a curative measure in a number of ailments, such as rheumatism, various disturbances resulting in skin troubles, inflamed and painful joints, and so forth. Incredible as it may seem, it is possible to pour boiling wax on any part of the human body without causing burns.

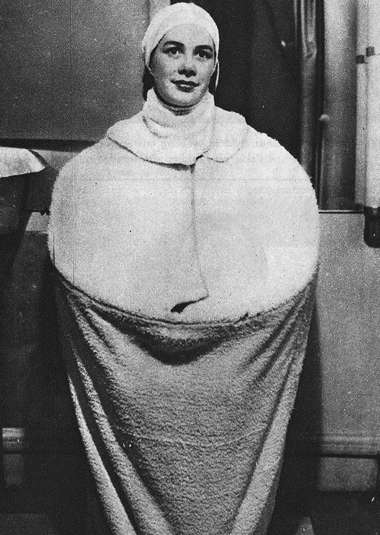

… The patient who is to receive a paraffin wax bath is placed in a wicker basket so built that his head is slightly raised. The basket is lined with a material impervious to wax. When all is ready the hot wax is poured over the patient so that his entire body is coated with it, or the part which is to be specially treated. When the wax cools, the patient looks as if he were covered with a plaster cast. After the wax has been poured on, the patient is covered carefully with a quilt, and remains in his wax bath just as long as the physician deems it necessary to bring about relief.(Bathing in melted wax, 1917, p. 578)

Above: 1931 Neo-Therapie Wax Spray Bath.

“Neo-Therapie is a wonderful new scientific application of remedial heat to the body that restores both beauty and health. Unhealthy conditions of the skin or system which mar beauty are corrected by the Neo-Therapie Wax Spray Baths which eliminate waste matter and impurities and aid nature to restore to the body the curves and skin of natural beauty.

Roughened skin and blemishes due to the rheumatic tendency are removed, obesity reduced, flesh built up in cases of abnormal thinness. The baths are of great value in cases of MYOSITIS, NEURITIS, NEURALGIA, LUMBAGO, RHEUMATIC or CHRONIC RHEUMATOID JOINTS, etc.“

Paraffin treatments

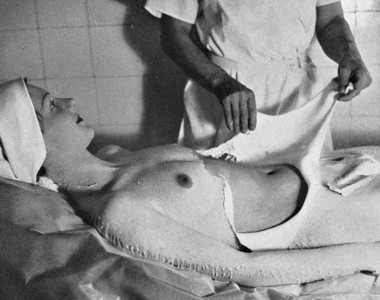

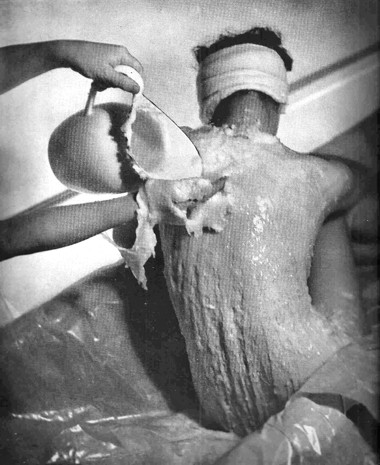

Paraffin was applied to the body in a number of ways. The hands and feet were generally immersed in a small paraffin bath and repeatedly dipped into the paraffin until a sufficient thickness of wax was built up. Parts of the body that could not be immersed were coated with paraffin using a paint brush, sprayed with paraffin using a mechanical sprayer, or had paraffin poured over them from a jug or ladle. The paraffin was normally left on for between 10 and 30 minutes during which time the treatment area could be wrapped in foil, a blanket, or some other material to help it retain heat. After the treatment was completed the paraffin was peeled off, a process made easier if a little mineral oil had been added to the paraffin to make it more pliable.

Beauty treatments

After they were adopted by physical therapists, paraffin baths were embraced by beauty culturists but put to different uses. In Beauty Culture the two main uses of paraffin wax baths were to hydrate and soften the skin, and to contribute to weight reduction; both treatments that rely on the ability of warm paraffin to induce perspiration.

Weight reduction

Using heat to induce perspiration has long been used to help reduce weight. Placing a client in a dry heat or vapour cabinet for a period of time induces a measurable weight loss due to dehydration. Although the ‘effectiveness’ of these treatments was primarily due to the amount of water lost, the positive result was generally explained to the client as being due to the effect of the heat on the blood circulation, body impurities or body fat.

A paraffin or wax ‘bath’ also induced perspiration so many beauty salons covered clients in wax as part of a weigh-reduction treatment. For example, Elizabeth Arden’s clients, looking to lose some pounds or kilos, were first treated with a ‘Roller’ to whittle away ‘unwanted layers of flesh’, then covered with wax in an ‘Ardena Wax Bath’ and finally massaged; all treatments considered at the time to be able to remove body fat.

You are stretched out on a couch covered with towels and a layer of grease-proof paper, and warm liquid paraffin wax is poured over you till you are coated with a layer of opaque white, like a wax image. But nobody sticks pins in you. Instead you will be covered with another sheet of paper, wrapped in a blanket, and left to simmer in a delicious warm bath that never changes its temperature. It’s not too hot, as in a Turkish bath, because your head is cooled, either by the the air from an open window, or by cold towels wrapped around your neck.

When you emerge from your cocoon, the wax peels off in long strips, the last vestiges washed away under a warm shower—and there you are, with skin white and soft as a child’s, rheumatic aches and pains charmed out of you, and a wonderful sense of well being. Now is the time to return to the battle of the bulges: the fatty spots, already worked on by the Roller, softened up and made malleable by the wax bath, will be particularly susceptible to the massage with which the full treatment is finished.(Harper’s Bazaar, 1947)

Above: 1952 Cyclax Wax Treatment (British Pathé, 1952). Hands could be used to smooth the wax over the body but applying it like this was rather clumsy and not generally recommended.

As wax could be used on specific areas it was also applied to reduce ‘unsightly flesh’ in particular spots, such as the ankles.

There is a new remedy for clumsy calves and unsightly ankles, and a new method of applying it. The remedy is hot wax, the method is spraying. One lies comfortably on a paper-covered couch and the wax is sprayed, like a warm and sticky rain, on to that too, too solid flesh. In a few minutes the wax sets into a firm shell of opaque white, in which one lies for perhaps half an hour. Under this shell the heated skin is throwing off, not only its surplus tissues of fat, but also all the impurities which lie immediately under the surface. For those whose not-so-slimness of leg consists of superfluous flesh the method should be ideal.

(Harper’s Bazaar, 1930)

Skin softening

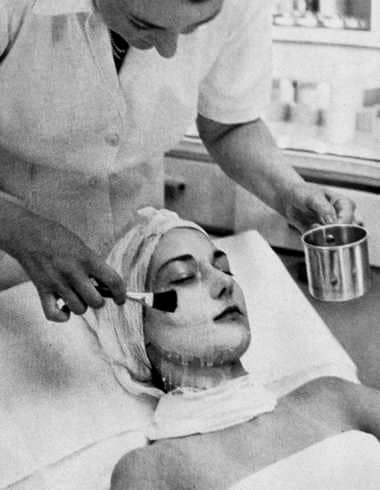

A paraffin wax treatment also softens the skin. As the perspiration induced by the heat cannot escape from under the wax, it hydrates the outer layers of the epidermis – the horny layer – producing a noticeable ‘plumping’ of the tissue. Beauty culturists used this effect by incorporating wax masks into facial treatments for dry and wrinkled skins.

Above: Paraffin wax face mask (British Pathé, 1932).

First a thorough cleansing; then comes stimulating massage with nourishing cream. The creamy traces are removed with special lotion, and the warm pink wax is painted on, and left to settle while you relax, with pads over your eyes. The wax peels off afterwards like the skin of a fruit. Your face is wiped clean with another lotion; then you have Oxylation—a refreshing spray of oxygen over the face and neck. Finally, a pretty make-up with Helena Rubinstein preparations.

(Harper’s Bazaar, 1949)

Paraffin wax treatments were also used in manicures and pedicures to soften rough hands or feet. After the nails and cuticles were treated, the forearm or foot was repeatedly dipped into a paraffin bath, wrapped, and then left for a time before it was massaged and had its nails painted.

Decline

Above: This more recent wax facial conducted in a French salon seems crude when compared with the 1932 treatment above.

The use of paraffin baths in beauty treatments has declined almost to the point of extinction. When used in weight-reduction or skin-softening treatments it became clear that results were limited and short-term. When this was added to the cost, mess, time to set up, and the extended treatment times, most salons operating today would not consider it worth the trouble. Those treatments that survive generally form part of a deluxe manicure.

Update: 25th July 2019

Sources

Bathing in melted wax. (1917). Popular Science Monthly. 90 January-June, 578-579.

Delorme, E. (1919). Les enseignements chirurgicaux de la grande guerre. Paris: A. Maloine et Fils.

Gallant, A. (1993). Principles and techniques for the beauty specialist (3rd ed.). Cheltenham, England: Stanley Thomas.

Kovács, R. (1949). A manual of physical therapy. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

Stafford, A. M. (1926). A handbook of physio-therapy. Chicago: Medical and Surgical Publishing Company.

A medical paraffin wax bath. The arm would be repeatedly dipped into the paraffin to allow a good coat to be built up (Kovács, 1949).

1930 Neo-Therapie Wax Spray Bath.

1934 Institut de Beauté Rene Rambaud.

1935 Phyllis Earle Wax Bath.

1936 Parisian Reducing Treatment: 1. Attendant filling jug with paraffin wax.

1936 Parisian Reducing Treatment: 2. Applying the paraffin wax to ‘break down and dispel fatty tissue’.

1936 Parisian Reducing Treatment: 3. After the paraffin treatment the client is then placed in a hot vapour cabinet.

1937 Phyllis Earle Wax Treatment.

1938 1. Paraffin body treatment in a Paris salon.

1938 2. Peeling the paraffin off after the body treatment in a Paris salon.

1938 Elizabeth Arden Ardena Wax Bath.

1949 Helena Rubinstein Plastic Mask.

1956 Elizabeth Arden Wax Bath at her Maine Chance health resort. The operator is pouring on wax from a jug and smoothing it out with her hands. The wax treatment could be followed by a Firmo-Lift Treatment and/or a session in a heated cabinet.