Rachel

Early face powders produced for the mass market came in three shades: Blanche (white), Naturelle (pink), and Rachel (cream).

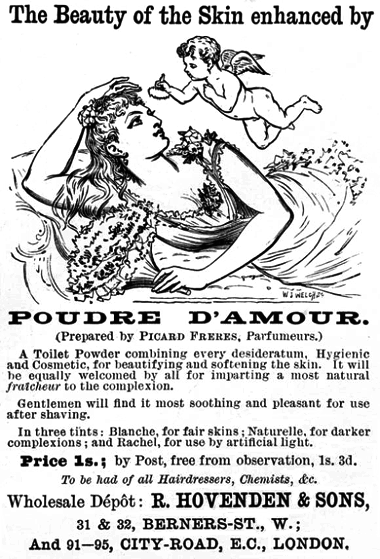

Poudre D’Amour a toilet powder for the complexion 1/- in three tints – Blanche – Naturelle – Rachel.

(Illustrated London News, 1892)

Empire Thespian powder for beautifying the complexion. This is an indispensable adjunct to ladies’ make-up, either for stage or private use, and is pecially prepared in three shades—Blanche (white), Naturelle (pink), Rachel (cream).

(Adair Fitz-gerald, 1901, p. 21)

The two most important tints of colour are rachel and naturel, the former a creamy-yellow and the latter a creamy-pink.

(Poucher, 1932, p. 557)

As the names used for these powders were French, the question arises why the colour ‘cream’ was called Rachel and not Crème. Who was Rachel?

The French actress

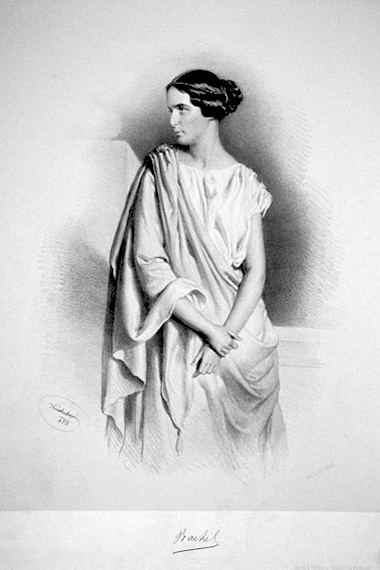

Élisa Rachel Félix came from an impoverished background, but with a prodigious talent, some luck and the attention of men with important connections, she rose to become a great classical French actress. Taking the stage name Rachel, she toured throughout France, Europe – from England to Russia – and the United States. She died from tuberculosis at the relatively young age of 38, which meant that, like others who have died prematurely, her beauty was locked in time.

Described as “one of the greatest actresses France, or perhaps the world, has ever known” (Hartnoll, 1976, p. 785) she was associated with grace and beauty.

It is almost impossible to conceive anything human more nearly reaching perfection than the symmetry and grace which Rachel presented in “Phédre.” Every step seemed to flow naturally out of what preceded, her every gesture moved in rhythmical accord with the verses that flowed from her lips, while, robed in the superbly ample peplum of the Greeks, this high-priestess of the histrionic art moved a goddess on the mimic scene.

(Shoemaker, 1980, p. 128)

One factor that may have helped her was the adoption by theatres, from the 1840s, of gas lighting. Stages in gas-lit theatres were much brighter than those lit by candles or oil lamps. Improved lighting required better sets and costumes as these were now more visible, but they also enabled the bodies, faces and facial expressions of the actors to be more clearly seen. The highly exaggerated facial expressions and gestures necessary with the dimmness of candle or oil light became passé. Rachel was known for her beauty, her clear diction and unexaggerated style of acting making her well suited for a stage with brighter light. Talented and beautiful, she was ideally placed to make the most of the new environment. It is understandable then, that her name might be associated with a beauty product. She was an actress, a beauty, and known throughout Europe.

In those convenient little powder books there are pretty new books that have satin covers blue, pink, heliotrope, red—all colors—and they do not cost more than the ordinary books. There is more to them, too, than the attractive outside. Whoever will polish away the soil of a Summer day’s trip through the streets may do it with a sheet of powder which has her own particular tone of complexion; there is rose, white and “Rachel”—named for the famous actress—and a brown tint for brunette.

(New York Times, 1905)

But why creme and not pink or white? Most likely, the colour suited her skin tone better than Blanche or Naturelle. As the advertisement for Poudre D’Amour suggests, it is to be used to give a natural fraîcheur (freshness) to the complexion in artificial light.

Stage makeup during Rachel‘s time was powder-based. With the arrival of greasepaint in the 1870s and its numbered colour system, the link between the actress and the colour began to be lost in theatrical makeup. However, as powder became more acceptable for general makeup, shade names used in the theatre crossed over into common usage.

Cosmetiques are no longer a feature of the make-up requirements. Grease-paint can accomplish all that has heretofore been done with cosmetiques, and with more satisfactory results.

(Young, 1905, p. 18)

Also see: Greasepaint

Although the collective memory of the link between the actress and the creamy colour was gradually lost, her name persisted, although it could also be spelt as Rachelle, presumably as this looked more ‘French’. As the range of powder colours increased in the twentieth century we also had the addition of other Rachel shades – Elizabeth Arden for example made a Rachel No. 1, Rachel No. 2, Rose Rachel and Special Rachel – with this proliferation of Rachels reaching its peak in the 1950s.

The other Rachel

Some sources suggest that the powder colour was not named after the French Élisa Rachel Félix but rather the English Sarah Rachel Leverson, known as ‘Madame Rachel’.

[B]y 1910 a lady’s handbag contained powder boxes of gold or silver filled with the first compact powders in white, flesh and rachel. The latter shade was named after a notorious English woman who made a disonest fortune by perpetrating fraudulent beauty treatments on silly women with no more beauty apparently than brains.

(Vail, 1947, p. 117)

Sarah Rachel Leverson was one of many purveyors of ‘beauty aids’ who operated in London in the nineteenth century. As usual, these aids were based on ‘secrets’ known only to her. In her case the ‘source’ of these secrets was the mystical East and she followed this theme in the labeling of many of her products, which included Arab Bloom Powder, Sultana’s Beauty Wash, Royal Arabian Cream and Magnetic Rock Dew Water of Sahara. It is possible that she learned how to make preparations from her first husband who was an assistant chemist.

As part of the sales pitch, she dangled stories of marriage to rich noblemen in front of her clients if they would undertake her treatments. This led to complaints, convictions for fraud, and to her dying in prison. Her trial at the Old Bailey was widely reported and followed up in poems, songs and plays of the day. It is this notoriety that probably led some to associate the Rachel shade with her, even suggesting that she made and named it herself. Examination of her product line listed in her pamphlet “Beautiful for Ever” does not show any powder of that name. She did make face powders but these were named ‘Arab Bloom Powder’, ‘Favorite of the Harem’s Pearl White’, ‘Albanian Powder’, and ‘Youth and Beauty Bloom’ so I think (with some relief) that we can discount this claim.

Updated: 28th April 2015

Sources

Adair Fitz-Gerald, S. J. (1901) How to make-up: A practical guide for amateurs and beginners. London: Samuel French.

Gunn, F. (1973). The artificial face: A history of cosmetics. London: David & Charles.

Hartnoll, P. (Ed.) (1967). The Oxford companion the theatre (3rd ed.) London: Oxford University Press.

Poucher, W. A. (1932). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (4th ed., Vols. 1-2). London: Chapman and Hall Ltd.

Shoemaker, J. V. (1890). Heredity, health and personal beauty. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis.

The Times. (1868). The extraordinary life & trial of Madame Rachel. London: Author.

Vail, G. (1947). A history of cosmetics in America. New York: The Toilet Goods Association.

Young, J. (1905). Making up. New York: M. Witmark and Sons.

1890 Advertisment for Poudre D’Amour a toilet powder for the complexion 1/- in three tints – Blanche – Naturelle – Rachel

Élisa Rachel Félix [1821-1858].

Sarah Rachel Leverson [1806-1880].

1868 Cartoon from ‘The Censor’ titled ‘Rachel – and her children!’. The three ‘beauties’ lining up for Madame Rachel’s cosmetics are Lust, Fashion and Folly.