Max Factor and Television

The Max Factor company is widely known for the make-up it developed for the motion picture industry in Hollywood but is less well known for its contributions to the make-up used during the early days of television.

See also: Early Movie Make-up and Panchromatic Make-up

Early television

Commercial television came to America during the 1940s and 1950s but, as in Europe, there were test transmissions earlier than this in the 1930s. These early tests demonstrated that conventional make-up techniques were not suitable for television as it existed at the time. Make-up that looked good in real life, or worked well in film, looked terrible on black-and-white television sets with images produced from between 240-343 lines or less. Along with the low definition, the way these camera tubes registered colour in shades of gray was also a problem and using make-up to compensate for these issues resulted in some bizarre looking faces.

Green Replaces Red in Make-up for Television

Green lipstick and rouge replace the customary red in make-up designed for actresses appearing in television broadcasts. The television camera, it is explained, does not record the red coloring in the human complexion, leaving the transmitted image flat and unnatural. When green is substituted, however, the lips and cheeks of a performer appear in accurate relation of tones with other facial features as the image is projected on the screen of the receiver.

(Popular Science, 1933)

The British Broadcasting Corporation’s (BBC) London Television Service – a non commercial broadcaster – experienced similar problems in the early 1930s. However, it had to deal with issues not experienced by later broadcasters as it was experimenting with transmissions in two forms, one of which was partly mechanical – the Baird system which only produced images made up of 30-60 lines. The BBC’s early electronic systems also had low line standards which resulted in fuzzy pictures. As in America, make-up was used to compensate for these issues.

Television

This new branch of entertainment has brought with it an entirely new technique of make-up. Here two considerations decide the kind of make-up to be used. The first is light sensitivity at the transmitter; the second is the degree of definition attainable at the receiving station. Since the received picture is in monochrome, that is black and white, or black and red, or black and green, colour does not appear on the screen. There are two methods of scanning the scene. One is to flood it with light and to scan it with a mechanical or electrical device. The other is to light it with a moving spot of light. Whatever coloured light is used, the colour used for the make-up must provide deep contrasts, but owing to the fact that the photo-sensitive cells used for transmitting are preponderantly sensitive to one range of colour the actual colour of the make-up must be the complementary colour of that which most affects the “electric eye.” Thus, if the cell is sensitive to red the make-up must be green. With such a cell, the actor would use green for shadows, wrinkles, eye shade, eyebrows, etc., while he would use red to soften out shadows and blemishes.

Again, the television screen shows a picture that is made up of lines of varying depth of shadow and light. Many factors limit the number of lines which can be used so that the picture is comparatively coarse and rather like a rough half-tone block. Definition of a very high order is therefore not yet practicable. Hence at the receiver, particularly with thirty-line television, the features are very blurred and indistinct. Soft graduations of details in the actor’s face are lost altogether. For this reason in the chief purpose of television make-up to increase the contrast. The lips, nostrils, and eye shadows are very deeply made up with green or purple according to which system is used, and any facial lines to be emphasized are lined in with the same colour. Shadows which have to be removed are covered with colour of the same hue as that to which the photo-cell is most sensitive, which, in the case mentioned above, where green was used for heavy contrast, would be red. The same considerations enter into the costumes used in television. Only when photo-cells can be made panchromatic and the definition of television systems increased to the fineness of the cinema film will ordinary cinema make-up technique be of any use.(Foan & Bari-Woolls, 1936, p. 500)

The Max Factor company had developed a make-up for this new medium as early as 1932 when working with the pioneer Don Lee Television station W6XAO in Hollywood, California and had even trademarked the term ‘Television Make-up’ at that time (Max Factor, 1958). The techniques used by Max Factor changed rapidly during the 1930s as the technology evolved. Some of these can be seen in images on this page.

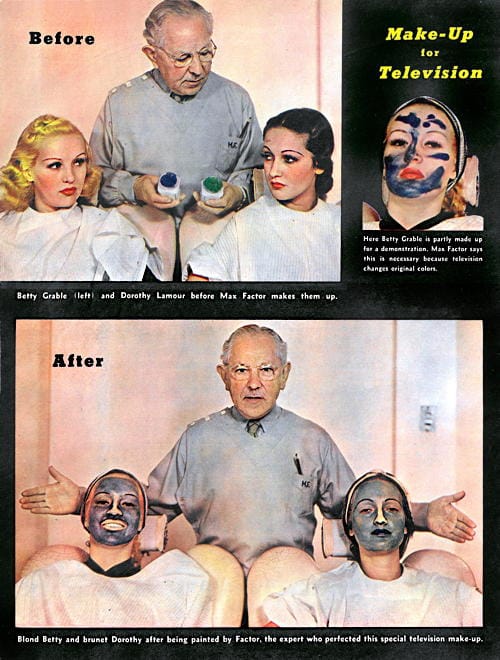

Above: 1937 Max Factor [1872-1938] demonstrating television make-up using the actresses Betty Grable [1916-1973] and Dorothy Lamour [1914-1996]. Max is primarily using what looks to be blue and green greasepaint (Look Magazine).

Rapid improvements

Fortunately, things improved very quickly in the late 1930s. When the BBC began television broadcasting in 1936 they did so in ’high-definition’. These transmissions produced images made up of 405 lines which meant that the make-up used in the broadcast avoided most of the weirdness of the past.

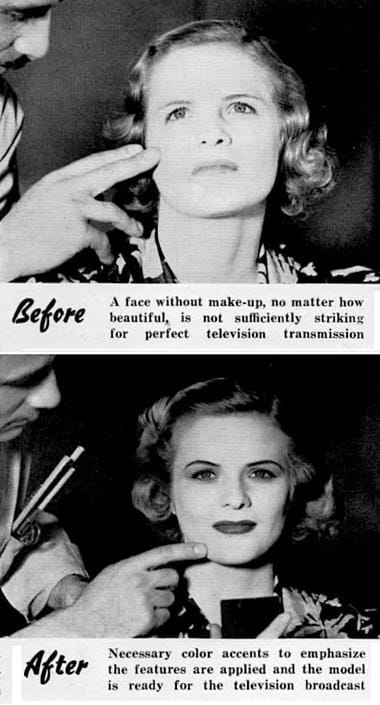

Above: 1936 Make-up used in the BBC broadcast.

Similar advances had occurred in the United States as well by the end of the decade.

Weird make-up which was previously used for television, with its chalk-like base, blue lipstick and blue contour lines, is now a thing of the past. Television has progressed far beyond the point where such exaggerated coloring is needed to emphasize contour and obtain clarity. Technical improvements of the last few years and the change from a mechanical system of scanning to the all-electronic system have made it possible to utilize a method which approaches natural make-up much more closely.

A specialized system of make-up is still necessary, however, to meant the peculiar demands of this medium.(Television. What does it require of make-up?, 1938)

Post-war television

Television imaging improved even further after the Second World War. In America, this was mainly due to the introduction of Image Orthicon cameras developed by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). First announced in 1939, Orthicon cameras produced images of 525 lines and their increased sensitivity meant that they began reproducing grey tones as faithfully as panchromatic film, something predicted by Foan & Bari-Woolls back in 1936. This enabled the Max Factor company to adapt its Pan-Cake make-up to television in 1946. To emphasise this fact, the Max Factor company held a press conference in which they made-up two women – Jane Grant and Mary Wirt – using the old television make-up before applying the new natural looking form they had developed.

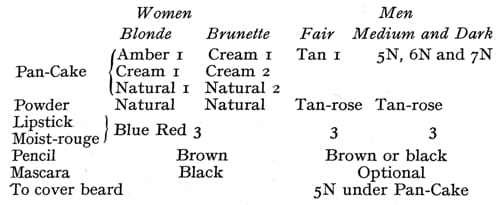

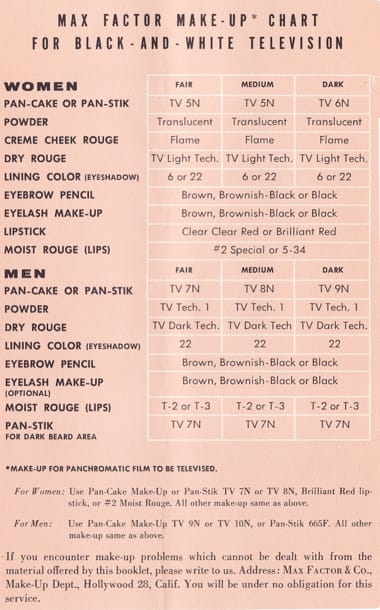

Above: 1950 Max Factor make-up chart for American television (Foan & Wolters, 1950, p. 455)

See also: Pan-Cake Make-up

However, some allowances still had to be made for television.

The principal challenge television offers to experts in the field of make-up is that infra-red rays filter out the normal red tones from the image, and red is transmitted as white. In photography, unless a special or panchromatic film is used, red tends to reproduce as a decidedly deep tone. For instance, we all know that in snapshots a red dress is likely to look black, and lips, if heavily rouged, appear unnaturally dark. On the television screen, however, ordinary rouge and lipstick (based on a range of reddish shades) would give an effect of pallor rather than an accentuation of the natural color!

To overcome this difficulty, dark brown is chosen for lip coloring in the most advanced television make-up technique. Coloring for the cheeks, if it is used, is a similar shade. Foundation cream is an orange peach, applied smoothly and evenly to cover tiny irregularities in the skin's surface and to give it a velvety finish. Eye make-up is emphasized much more strongly than for street wear, but is not applied as heavily as for the stage, since the distance between actress and television camera is less than that between a stage actress and her audience. Mascara, applied to the brows and lashes, is such a dark brown that it is almost black. Eye-shadow, in a brown shade, emphasizes the depth and luster of the eyes.(Modern Beauty Shop, 1938)

Blue is almost always darker on the tube than to the eye, so eyeshadow with blue in it has to be cautiously applied, but the usual colours are, as in films, blue-grey or brown.

Men’s beards present a problem that is peculiar to the medium, for even a very closely shaved face is liable to show the beard as a dirty patch. This has to be obliterated with a light putty coloured grease before the final groundwork is applied. Shadows under the eyes are troublesome, and even very young faces have to have highlighting there. False eyelashes have to be tested on each artist, for on some occasions they will darken the eyes to “burn holes in a blanket” while another time they will enlarge them.(Foan & Wolters, 1950, p. 455)

Colour television

The arrival of colour television introduced some new problems. In the early decades of colour television, programs broadcast in colour were also being watched on black and white receivers. This explains why many early television programs filmed in colour look so highly coloured when viewed today. Compare, for example, the bold colours in the first series of Star Trek, which started broadcasting in 1966, with the muted pastels of Star Trek: The Next Generation which began in 1984. The bold Star Trek colours were selected so that they would give good contrast when viewed on black and white receivers.

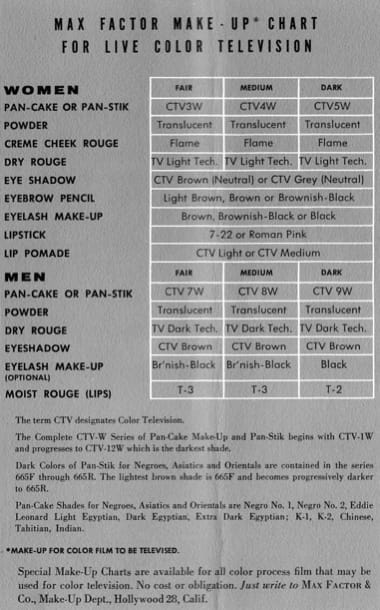

Predictably, in 1954, the Max Factor company unveiled a make-up range suitable for black and white and colour televison as well. It was available in Pan-Cake as well as the company’s more recently developed Pan-Stik make-up.

Principal pigmentation colors apparent in the human skin are red, blue, yellow, brown, and gray. These colors have different wave lengths and reflect light with various intensities. Therefore, even a naturally flawless complexion without make-up, provides a major problem by showing varying degrees of blotchiness when reproduced over television. This is true of both men and women. Light complexions will come through a spotty, ghostly white. Dark complexions will look plain dirty. Men look as though they need a shave, regardless of how closely they may have shaved, unless make-up is used. Even the woman who is beautifully made-up with her everyday society make-up materials isn’t at all prepared for the television cameras. Her foundation make-up will televise as though it were either much too light or much too dark, with a mottled complexion appearance being evident in either case. Her ordinary lipstick shades will usually televise much too light, and most of her everyday rouge shades will be altogether too dark.

The application of Max Factor TV Pan-Cake Make-up or TV Pan-Stik Make-up creates a monotone complexion finish from which light is reflected evenly and in the same intensity, thereby resulting in a clean, smooth skin tone. None of the many serious complexion defects previously mentioned can become apparent to the TV camera when either of these make-up foundations has been correctly used.(Max Factor, 1958)

Also see: Max Factor: Television make-up for black-and-white and color television

The Max Factor company had spun off its industry developments into general make-up before as, for example, with Pan-Cake, and had used its preeminence in the movie business to promote its general make-up between the two World Wars. The company tried to replicate this strategy with televison when they released their Hi-Fi line in 1955. The company claimed that Hi-Fi had come from its research into colour television make-up and that this had created a make-up that produced “new high fidelity skin tones never before possible” (Max Factor advertisement, 1956).

See also: Max Factor (post 1945)

First Posted: 22nd March 2009

Last Update: 21st November 2024

Sources

Basten, F. (2008). Max Factor: The man who changed the faces of the world. New York: Arcade Publishing.

Farnsworth Television, Inc. (1939). The birth of television, San Francisco, California.

Fisher, D. E., & Fisher, M. J. (1996). Tube: The invention of television. Washington: Counterpoint.

Foan, G. A., & Bari-Woolls, J. (Eds.). (1936). The art and craft of hairdressing: A standard and complete guide to the technique of modern hairdressing, manicure, massage and beauty culture (2nd ed.). London: New Era Publishing Co., Ltd.

Foan, G. A., & Wolters, N. E. B. (Eds.). (1950). The art and craft of hairdressing: A standard and complete guide to the technique of modern hairdressing, manicure, massage and beauty culture (2nd ed.). London: New Era Publishing Co. Ltd.

Max Factor. (1958). Television make-up for black-and-white and color television [Booklet]. USA: Author.

Television. What does it require of make-up? (1938). Modern Beauty Shop. August, 56-57.

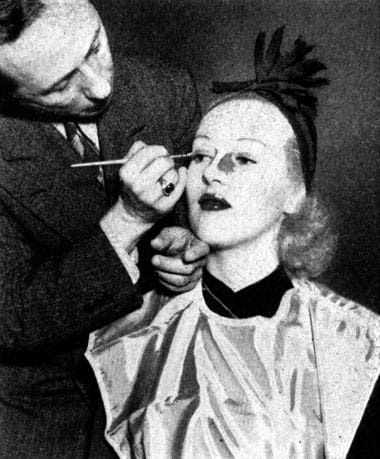

1933 Betty Grable, film star, being made up for television by Abe Shore (Abraham Bernard Shore [1894-1957]) (Popular Science). Abe was Director of Make-up at Max Factor for a while in the early years of the company. He had married Freda Factor [1898-1988], Max Factor’s daughter, in 1923.

1938 Make-up for television with higher line standards (Modern Beauty Shop).

1939 Make-Up for Television. “Elaine Shepard, Hollywood film actress, could pass for an Indian in war paint when she wears the new standard television make-up. White high-lighting around the nostrils, eyes and hollows of the throat is necessary for good reproduction. Lips, eyebrows and eyelashes are blue-black” (Mechanics Illustrated). By the time this article was published this type of make-up was already out of date.

1939 Frank Factor [1904-1996] making up a dancer for television. This image and three that follow come from the film ‘The Birth of Television’ released January 6, 1939 so were probably taken in 1938 when this sort of make-up was coming to an end.

1939 The completed make-up of the dancer giving some idea of the colours used.

1939 Dancer made up by Frank Factor as seen on the television screen.

1939 An announcer made up for television. Note the overal brown colouring and blue lips.

1946 Jane Grant and Mary Wirt wearing early black-and-white television make-up before putting on the new, more natural looking make-up developed for television by the Max Factor company.

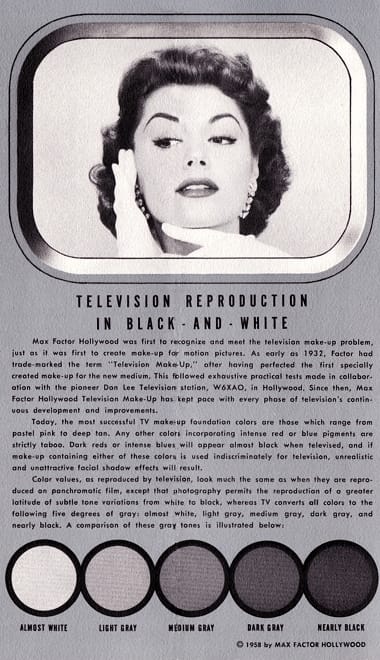

1958 Higher definition television cameras which came into use in the late 1940s reproduced colour more like black-and-white panchromatic film. This enabled the Max Factor company to adapt its panchromatic make-up to the new medium.

1958 Max Factor make-up chart for black-and-white television.

1958 Max Factor make-up chart for colour television.

1956 Max Factor Hi-Fi Fluid Make-up.

Agnes Moorehead [1900-1974] as Endora in the TV series ‘Bewitched’ which began in 1964. Early colour broadcasts also had to work on black-and-white television receivers so the sets and make-up used in the 1960s often look overly coloured by today’s viewers. This was necessary to provide sufficient contrast on the black-and-white receivers.